Feb 2, 2015

Stan Mikita, Al Arbour and the afflictions affecting them

Chicago Blackhawk legend Stan Mikita and former player and Hall of Fame coach Al Arbour are facing their own serious health issues related to neurological afflictions. TSN Hockey Insider Bob McKenzie wonders what the possible causes were and where head trauma in hockey is headed.

By Bob McKenzie

Some days - not too many, thankfully - I feel like it sucks to get old. Or, more precisely, it sucks to watch great hockey people you admire and respect grow old.

Friday was one of those days.

That's when the family of 74-year-old Stan Mikita announced the Hall of Fame Chicago Blackhawk centre and beloved franchise ambassador is facing serious health issues, that he has "been diagnosed with suspected Lewy Body dementia, a progressive disease and is currently under the care of compassionate and understanding care givers."

On the same day as that most unwelcome Mikita news, blogger Howard Berger (bergerbytes.ca) posted a current photograph of 82-year-old former NHL defenceman and Hall of Fame coach Al Arbour, updating his condition (dementia and Parkinson's Disease) and inviting fans to send best wishes to Arbour at his retirement home in Florida. Arbour's health issues were widely reported in the media last summer - it isn't necessarily 'news' he's now suffering dementia - but what's that they say about one picture being worth a thousand words?

That the failing health of these two Hall of Famers intersected, sadly, on the same day only added to the magnitude of the misfortune. At least it did for a kid who spent his formative Original Six hockey years growing up in Toronto in the 1960s, admiring the two men for very different reasons.

***

I loved Stan Mikita's hockey stick before I came to fully appreciate him as a hockey player. Bobby Hull's too.

The two Blackhawk stars were, of course, the most famous originators of the curved stick in hockey. I don't want to say you had to be there in the 1960s to truly comprehend the impact of that phenomenon on the game but, really, you had to be there.

My friends and I were totally enthralled and captivated by it. You had to see a Mikita or Hull curved blade to believe it. Not for nothing were they called banana blades, more boomerang than blade. Perhaps not coincidentally, (then hockey equipment manufacturer) Cooper came out with what was known as the Super Blade, a plastic road hockey blade that could be affixed to a wooden stick shaft.

The beauty of the Super Blade (aside from the fact it was more or less indestructible and ran more smoothly than wood over asphalt) was you could curve it as much, or as little, as you liked. Right or left, it didn't matter. My friends and I preferred a lot over a little, thanks to Mikita and Hull. You had to heat the blade over a stove top to curve it. My Mom always feared I would burn down the house while curving my Super Blade, but, truth be told, boiling the water to mold my Cooper Adanac inside-the-mouth mouth guard for real hockey was far more dangerous, but that's another story.

We all wanted to be Stan Mikita and Bobby Hull when we played road hockey, the ultimate compliment coming from kids raised on Punch Imlach's Maple Leafs. If it wasn't too cold out, you could take your Super Blade and add extra curve to it by sticking it in the sewer grate and bend it to absurd proportions.

Mikita and Hull, of course, were so much more than their curved sticks. Hull was The Golden Jet, along with Gordie Howe, the biggest name(s) in the game. Mikita, as much as he was a star, was also complex and contradictory, so many things to so many people.

My Dad often referred to Mikita as a, "dirty S.O.B." And, for a time, he was. In his first six years in the NHL, Mikita had 100 or more penalty minutes in each of four seasons (154 was his personal best or is it worst?), 97 in one of the two years he didn't hit the century mark. Stosh, as he was known, was mean, not afraid to use his stick for more than scoring goals. No one ever doubted his skill and offensive ability – in his second NHL season he played a significant role in the Hawks' 1961 Stanley Cup victory and was legitimate star who won four NHL scoring titles in a five year stretch between 1963 and 1968 - but Mikita was often one nasty bit of business.

If the advent of the curved stick revolutionized the game on one level, Mikita effected what had to be one of the most remarkable individual transformations in the history of hockey on another.

So, in back-to-back seasons (1966-67 and 1967-68), Mikita not only won the Art Ross Trophy as NHL leading scorer and Hart Trophy as NHL MVP, but he also won the Lady Byng Trophy as the league's most gentlemanly and sportsmanlike player. It was a stunning reversal. Two scoring titles, two MVPs, two most gentlemanly player awards, with penalty minute totals of 12 and 14, in two years after being one of the NHL's most notorious bad boys and stick men. He remains the only NHL player to win those three trophies in the same season, and he did it twice.

Mikita was a special player. Only a special person could re-define himself the way he did.

If I went to my uncle's house on a Saturday night, when the Hawks were playing the Leafs, Mikita was a revered figure there. My uncle married into a Polish family, and though Mikita was born in Czechoslovakia (he moved to Canada when he was eight), that was close enough for fellow Eastern Europeans to identify with. They loved him.

We knew from Mikita's hockey card that his original name was Stanislav Gouth, born in Czechoslovakia (Slovakia actually). He was raised in St. Catharines, Ont., by his aunt and uncle and took their last name - Mikita. By any name, he was extraordinary.

His innovating ways didn't end with the curved stick. Mikita was reportedly knocked unconscious by New York Ranger defenceman Rod Seiling in a 1968 playoff game. According to accounts, Mikita left the game for a few minutes and came back to lead his team to victory. He subsequently helped to design and wore what became known as his trademark bulbous Stan Mikita model helmet, one of the first NHL veterans to opt for protective headgear.

Al Arbour, meanwhile, could not have been more different than Mikita. He wasn't an offensive star; he wasn't a star at all. He was a defensive defenceman who had to battle just to hang on in the NHL.

Funny enough, and I didn't know this until now, Mikita and Arbour were teammates on the Cup-winning 1961 Hawks. For the better part of the 60s, between 1962 and 1967, Arbour was more an American Leaguer with the Rochester Americans than he was a Maple Leaf. That, I always knew. A kid growing up in Toronto in the 1960s knew 'em all, the Leafs and the wannabe Leafs in Rochester. The Amerks even played some games at Maple Leaf Gardens and I'd go to watch them there.

Then there was Arbour's hockey card. My friends and I were fascinated by it. We loved that Arbour's name was, in fact, Alger, but more importantly, that he wore glasses, both in the photo in his hockey card and on the ice. That alone distinguished him from every other hockey player. As such, we reserved a special sort of attention for this Alger Arbour fellow. Then expansion came in 1967 and he was off to St. Louis to become captain of the Blues and, ultimately, to make a far greater impact as a coach than a player.

***

That kid in Toronto never would have imagined growing up one day to work in the hockey business, getting up close and personal with the faces and people he had only ever saw on TV or on a hockey card. That experience can be a double-edged sword because that's when you find out some of your childhood heroes or hockey stars may not be exactly who you thought they were.

Suffice to say that never happened with Stan Mikita or Al Arbour.

Post retirement - chronic back woes forced Mikita to call it quits during the 1979-80 season -- any occasion I came across Mikita, he was so cool and charismatic. He had a regal air about him. He was the nattiest of dressers, a real sharp-dressed man. When Bobby Hull and Mikita were at functions together, Bobby could be ribald and crass, Stan would be smooth as silk and all class, though you knew he still, in a very good way, had a little bit of the devil in him, too.

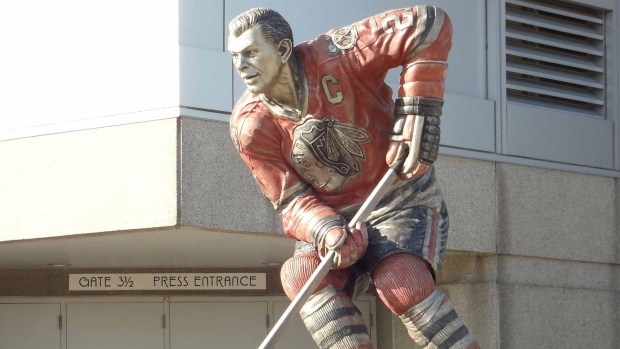

When the new regime of the Blackhawks finally welcomed their superstars – chiefly Hull and Mikita – back into the fold after decades of neglecting them, Stan the Man took his ambassadorship to heart and assumed, quite rightfully, exalted status within the organization. He's a veritable icon in Chicago and has the statue outside the United Centre to prove it.

By the time I started covering the NHL in 1982, the still bespectacled Arbour was in the midst of coaching the four-Cup dynasty of the New York Islanders and well on his way to becoming a legendary bench boss, who even today is second only to Scotty Bowman in career wins.

He was always patient and caring and friendly with inquisitors and for a young media guy breaking into the business that was appreciated more than he would ever know. Arbour and his boss, Islander general manager Bill Torrey, were great at their jobs. At their very core, though, you could tell they were just good people. Al's players loved him. Over the years, when I would work in TV with former Islanders, first Glenn Healy and now Ray Ferraro, they would always speak so lovingly of him. They had great insights into him as a coach and wonderful, funny stories of him as a man, which made him all the more endearing. Their respect, admiration and affection for him came off them in waves.

***

Diseases that attack the brain are insidious things.

I know this only too well.

My maternal grandfather's quality of life - and ultimately his actual life - were taken by a degenerative neurological disorder that eventually robbed him of his ability to walk, talk and engage in any semblance of coordination.

My Dad died of brain cancer, a tumour. It was astonishing how quickly after he was diagnosed that he was robbed of his faculties. Intellectually, mentally, he was long gone before the cancer claimed his physical life.

It isn't pretty watching someone go down that road, whether it's cancer, Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, dementia, Lewy Body or otherwise, and who knows what other neurological time bombs that may be out there. I'm sure many of you know that only too well from your personal experience, just as the loved ones and friends of Stan Mikita and Al Arbour are dealing with it now. The same goes for the Gordie Howe and his family, who have been dealing with Mr. Hockey's dementia for years, quite aside from his recent health scares involving stroke(s).

As much as I can relate to that, I'm also a journalist, curious by nature, and as sad and empathetic as I was with Friday's news, I must admit I also wondered if there might be any connection between the brain diseases afflicting Mikita and Arbour (Howe, too) and having played professional hockey, possibly suffering brain trauma along the way.

I am not a doctor, too dumb to have even considered the notion.

I also know millions are afflicted with dementia or Alzheimer's or Parkinson's and most of them never played so much as a game of hockey or football or anything that caused repetitive brain trauma.

These things often just seem to happen, especially with those in their seventies and eighties. Maybe that's simply the case here. We don't know; we're not likely to ever know.

Still, that doesn't stop me from wondering. We can't ignore the reality of what has gone on in sports and medicine in the last 10 years, especially in the National Football League: all the research that has been done by forensic pathologist Bennett Olamu, Dr. Ann McKee, a neuropathologist, and Dr. Robert Cantu, a neurosurgeon, as well as so many others who have linked, in varying degrees, repetitive head trauma in football, boxing, wrestling, hockey and other contact sports, to Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, a progressive degenerative brain disease that, for now anyway, can only be definitively diagnosed after the patient has died.

If you haven't read the book, League of Denial: The NFL, Concussions and the Battle for Truth, by Steve Fainaru and Mark Fainaru-Wada, you really should. It chronicles not only the NFL's reticence to deal with the head trauma/CTE issue but the in-fighting amongst medical practitioners to be at the forefront of the movement. It's a fascinating read, a subject that isn't going away.

Mostly, though, the book specifies the tragic lives and deaths of football players with CTE who were afflicted with a wide range of early onset neurological disorders that quite likely contributed to their deaths.

Medical evidence isn't as plentiful, at least not yet anyway, in hockey as it has been in football, but Dr. McKee's work with the Boston University brain bank – where the brains of deceased athletes are studied for CTE – has yielded connections between deceased NHLers and CTE.

Original Six tough guy/enforcer Reggie Fleming had a long history of behavioral and cognitive issues. After his death in 2009, at the age of 73, his post-mortem brain examination confirmed the presence of CTE.

Similar autopsies on ex-Buffalo Sabre star Richard Martin, who died of a heart attack at age 59 with no apparent or overt neurological disorders, and legendary NHL tough guy Bob Probert, who died in 2010 at age 45 of an apparent heart attack, also confirmed the presence of CTE.

Most recently, a brain autopsy on NHL tough guy Derek Boogaard, who died at age 28 in 2011 from what was deemed to be an accidental death (mixing alcohol and oxycodone), also revealed CTE.

In the wake of that, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman was quoted as follows: "There isn't a lot of data, and the experts who we talked to, who consult with us, think that it's way premature to be drawing any conclusions."

Fair enough. It's a serious issue and it deserves to be treated seriously, with empirical data and hard evidence. Time will tell how it all plays out for hockey.

But as someone who's been around this game for the better part of my life – recognizing I certainly have none of that hard evidence or empirical data -- I do sometimes get a terrible sense of foreboding, that as the speed of the game has dramatically increased every decade since the 1960s, both the quality and quantity of impact to the players' brains have increased, too. Perhaps we're only looking at the tip of a very large iceberg in hockey.

I know some retired NHL players who played in the 1980s and 1990s who estimate they've suffered 10 to 15 concussions, experiencing all manner of symptoms and issues. I've talked to these players; I've worked alongside some of them in television. I won't lie. I fear for them and hope beyond all hope my fears are unfounded, that hockey's terrible day of reckoning on head trauma exists more in my mind than reality.

In the meantime, me wondering about the possible causes of Stan Mikita's and Al Arbour's neurological afflictions, as well as where brain trauma in hockey may be headed, doesn't alter my feelings from Friday in any way: that is, the sadness and empathy I have for two marvelous hockey men I so admired when I was a kid.