Aug 9, 2016

Demers isn’t lucky, but he’s good

Florida defenceman Jason Demers was available this summer at a bargain price because of a couple of variables that were out of his control, Travis Yost writes

By Travis Yost

Last Thursday, I was asked by a reader to identify the most underrated move of the off-season. Only then did I realize that I hadn’t yet written about the Jason Demers signing in Florida – an under-the-radar acquisition that positions the Panthers quite nicely on the blueline for the next few years.

There’s no question that Demers can play. He’s been a very reliable top-four option for years in various environments at both ends of the ice. The perception about his game is that he’s more of a defensive defenceman, but that label glosses over the fact that he’s 26th in 5-on-5 scoring (per 60 minutes) among all defenders in the last four years – ahead of offensive-minded blueliners like Keith Yandle, Nick Leddy and Kevin Shattenkirk.

The more interesting piece of the signing is that it cost the Panthers just $22.5 million over five years. It’s not as if age or mileage should have scared off teams, considering his multi-year contract expires at the age of 32. And, again, the scoring piece – the piece that historically drives contracts in the NHL – is there.

So, how did Florida get this capable and talented defender at such an affordable cost? My theory is that the market for Demers was artificially deflated by a couple of variables out of his control – enough to take a defender who should’ve made $5.5 million a year and turn him into a defender who is going to make $4.5 million a year.

Those variables are the shooting and save percentages his teams experienced with him on the ice the last few years. Despite Demers driving play on a year-by-year basis, he received little help in the randomness department. Remember, defenders cannot drive on-ice shooting percentages in any meaningful way, and the same is mostly true for their on-ice save percentages.

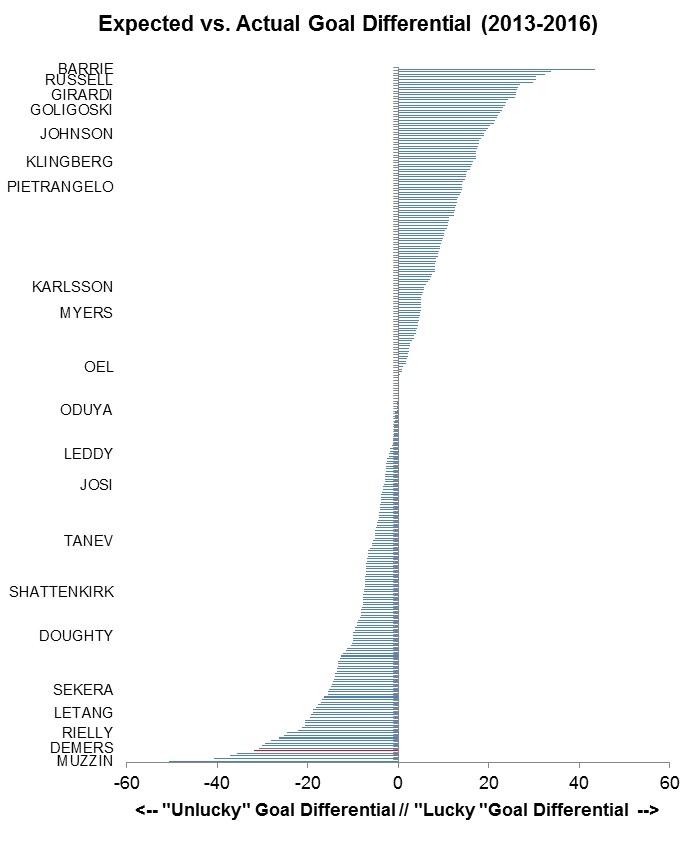

When you normalize for these external variables you can start to observe the types of players who have been, for a lack of better phrasing, lucky or unlucky over the course of a handful of seasons. Demers fits squarely in the latter category.

Below is a straight variance between a player’s expected goal differential (using Corsica’s methodology) against a player’s actual goal differential. The theory here is that players who are running high negatives probably were victimized by poor puck luck and/or poor surrounding talent, especially in the goaltending department. The opposite is true for players who are running high positives – these players probably benefited from great puck luck and/or great surrounding talent, especially in the goaltending department.

The way you read this is pretty simple. Take Colorado Avalanche defenceman Tyson Barrie for example. His expected goal differential at 5-on-5 for the last three years, based on shot differentials, shot quality and a myriad of other factors, was expected to be -22. His actual goal differential was +22. Therefore, the variance between the two is worth about 43 goals. (If you are curious, this is almost exclusively a result of the fact that Barrie’s on-ice shooting percentage was 9.8 per cent. The league average is about 7.6 per cent.)

On the other side, you have Demers. Despite being a very-good-to-dominant 5-on-5 player for years in both San Jose and Dallas, his actual goal plus-minus was +7. Unlike Barrie, Demers has below-average team-shooting talent in the last few years (around 7.4 per cent), and his on-ice save percentage was a substandard 91.7 per cent (league average in this timespan is about 92.4 per cent).

When you adjust for the fact that Demers hasn’t seem to have a ton of puck luck at either end of the ice, you start to observe that his expected goal differentials supersede his actual goal differentials to a fairly significant degree. Using the methodology mentioned earlier, we would’ve expected to see Demers at about a +39 goal differential in a normal environment – about 31 goals better than reality. That +39, by the way, would’ve been fifth best in the league, trumped only by Marc-Edouard Vlasic, Jake Muzzin, Justin Braun, and Drew Doughty.

I don’t know how much that cost Demers in free agency this summer, but I wonder what would’ve happened to his contract if he did get more of the right side of the bounces, especially in the defensive third. Either way, I don’t think it’s unfair to wonder if this is part of the reason his price appeared to be discounted in a free agency period where money was being handed out like candy to second- and third-tier players.