Feb 26, 2016

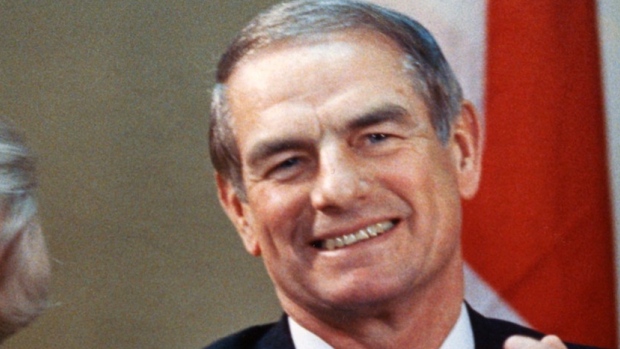

Former Eskimo Don Getty dies at 82

Don Getty, the broad-shouldered, bristle-topped kid who came west to champion Alberta dynasties in both football and politics, has died.

The Canadian Press

EDMONTON - Don Getty, the broad-shouldered, bristle-topped kid who came west to champion Alberta in football and went on to the top job in provincial politics died Friday.

Getty's family confirmed the former Progressive Conservative premier, who was 82, died in the early-morning hours of heart failure at an Edmonton long-term care centre.

His son, Darin Getty, said his father had been battling various illnesses for years.

"He fought right 'til the bitter end and I could see him fighting," said Getty, who talked to his father just hours before his death.

"He looked at me at one point and he said, 'I'm just all worn out.'"

"Premier Getty was a foundational leader in building much of what we all love best about our province today," Alberta Premier Rachel Notley said.

She noted that Getty served with her father, Grant Notley, who was leader of the NDP at the time.

"There was a tremendous level of mutual respect between both of them."

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in a statement, said Getty "guided Alberta through challenging economic times, was a strong proponent of Senate reform and worked in close collaboration with indigenous peoples across the province.

“Mr. Getty was a tireless champion of strengthening Alberta’s presence in Canada."

Ric McIver, interim leader of Alberta's PC party, said Getty reached the peak of performance both as an athlete and in the world of politics.

"The fact that he hit the pinnacle ... in two separate endeavours in his life really speaks to the drive and character of the man."

Getty's death is the final chapter in a storybook life: the kid from hard-scrabble roots who rose to become a football hero and marry his high school cheerleader sweetheart before reaching the peak of political power in Alberta.

The motif of his life was oil, the lifeblood of his adopted province, and it was the elusive black gold he tried to control that in the end dictated his fate.

Getty served as Alberta's 11th premier from 1985 to 1992 after winning a bitter PC party leadership race on the second ballot.

He replaced the legendary Peter Lougheed, the man at the helm when the PCs dethroned the Social Credit dynasty to launch a four-decade dynasty of their own.

Getty was sworn into office on Nov. 1, 1985, at age 52.

The honeymoon was short.

Almost as soon as he took over, a global oil glut saw prices plunge by 60 per cent. Alberta’s economy tanked.

The province was saddled with what at that time was a record $3.3-billion deficit in 1986. Five more deficits followed and the accumulated debt topped $15 billion.

Getty intervened directly. His government pumped billions of dollars into oil and forestry initiatives, new pulp mills, loans and sweetheart incentives to encourage drilling.

But problems mounted.

He was blamed for the failure of a number of government-backed businesses, the most costly of which was a $600-million loss on a cellular phone company called NovAtel Communications.

The province took over money-losing meat-packer Gainers Inc. after owner Peter Pocklington defaulted on loan guarantees Getty had personally approved.

When the Principal Group investment empire collapsed in 1987, the premier’s office told reporters he was working “out of the office.” A news photographer tracked him down on the golf course and snapped what became, fairly or unfairly, the enduring image of an annoyed premier fiddling with his five iron while millions of dollars in seniors’ life savings disappeared.

But there were successes.

He defused a potentially violent land dispute with the Lubicon Cree in northern Alberta in 1988.

In 1989, he passed a law for a February holiday called Family Day. Several provinces have followed suit over the years.

In 1990, the new Metis Settlement Act set aside land and granted self-government to eight Metis settlements.

In a bid to make the Senate more effective, Getty held the first senator-in waiting election in 1989. The winning candidate, Stan Waters, was appointed to the upper chamber a year later by then-prime minister Brian Mulroney.

Getty had a rocky relationship with Mulroney. He backed Mulroney’s bid for a free-trade deal with the United States but railed against the imposition of the GST in 1991.

He fought for the Meech Lake and Charlottetown accords to embrace Quebec in the Canadian constitutional fold.

"The greatest thing to me is to have tried,'' he said after the Charlottetown pact went down to defeat. “Perhaps it doesn't always work out, but not to have tried, now that would have been terrible.”

Getty led the Tories to majority governments in 1986 and 1989, but in the latter vote he was humiliated when he lost his own riding to the Liberals. Getty won a byelection two months later in a rural riding.

But things were never the same. There was discontent in the ranks. Rivals began pushing for a leadership change. Three years later, Getty stepped down.

Donald Ross Getty was born Aug. 30, 1933, in the Montreal suburb of Westmount. He came from scrappy Irish roots, the second of five children.

He grew up in Montreal and the family at times lived on welfare. When the Second World War came, his father took a job with the Royal Canadian Air Force, which forced the family to move to Ottawa, Toronto and eventually London, Ont.

In London, Getty went to the University of Western Ontario, where he starred in basketball, while leading the football team to championships in 1952 and 1953.

He played basketball and at 16 fell in love with cheerleader Margaret Mitchell, who often accompanied the team on road trips.

"I got to know her in the back of a bus," Getty once said, realizing as the laughter began that the line wasn’t expressed as intended.

"Jeez," he laughed. "That just came out."

They would have four sons.

On June 4, 1955, he graduated with a degree in business administration. Two weeks later he married Mitchell and they headed west so he could try out with the Canadian Football League Edmonton Eskimos.

In football, it was the era of high-top shoes, thin plastic helmets, tinny one-bar face masks and goalposts shaped like the letter H.

The Esks were a dynasty in the making with stars such as Jackie Parker, Rollie Miles, Johnny Bright and Norman Kwong, who would later serve as a lieutenant-governor in Alberta.

Getty was six-foot-two with a cannon for a right arm. Kwong nicknamed him “the Dino” because of his small head on a large frame and his lumbering running style.

He was with the Esks in 1955 when they won the second of three consecutive Grey Cups and came into his own in the 1956 championship when he got the surprise call from head coach Frank (Pop) Ivy to start at quarterback.

Getty was unflappable. When the Montreal Alouette defence stacked the line, he ran the ball wide. When they spread out, he gave the ball to Bright to bull rush it up the middle. He threw 16 passes for 104 yards and scored two touchdowns.

“Don kept as cool as a julep when a lot of young players might have pressed too hard,” Parker said afterwards.

Three years later, in 1959, Getty threw for over 2,000 yards and was runner-up as the league’s most valuable player.

He spent his whole career, 10 seasons, with the Eskimos and today ranks as one of the greatest Canadian-born quarterbacks to ever play the game.

When he hung up his cleats, he worked full time in the oilpatch and eventually formed his own company, Baldonnel Oil and Gas.

But by 1967 another former Eskimo, Lougheed, recruited him to run provincially for the Progressive Conservative party.

The Tories won six seats in 1967, one of them by Getty, and four years later ended the Social Credit's 36-year hold on power by securing a majority government.

Getty served as Alberta’s first minister of federal and intergovernmental affairs. But in 1975, as the price of oil skyrocketed, setting off an international crisis, he took over the critical energy portfolio.

He became Alberta's chief negotiator in acrimonious energy pricing battles with Ottawa that would culminate in then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau’s much-maligned national energy program of 1980, which put price controls and extra taxes on oil and gas production.

Wary of the toll hectic political life was taking on his family, Getty bowed out of politics in 1979 and returned to the oilpatch, only to be wooed back six years later to run for party leader when Lougheed retired.

He was asked in 2012 which endeavour was more enjoyable: football or politics?

Getty held up one hand to show off his Grey Cup championship ring.

“I think this may have been more fun,” he laughed.

In retirement there were accolades to enjoy. He was named to the Edmonton Eskimos Wall of Honour at Commonwealth Stadium in 1992. He was named an officer of the Order of Canada in 1998 and, in 2001, the new Don Getty Wildland Provincial Park west of Calgary was created.

In 2012, Getty stoop-shouldered and using a wheeled walker to get around, said he had no regrets.

“There were ups and downs all right,” he said. “But you wake up or go to bed at night with a tremendous feeling of satisfaction, being content that I had done everything possible to make Alberta a great place in the future.

“That’s a great sense of accomplishment.”