Apr 21, 2017

Raines opens up about cocaine use in memoir

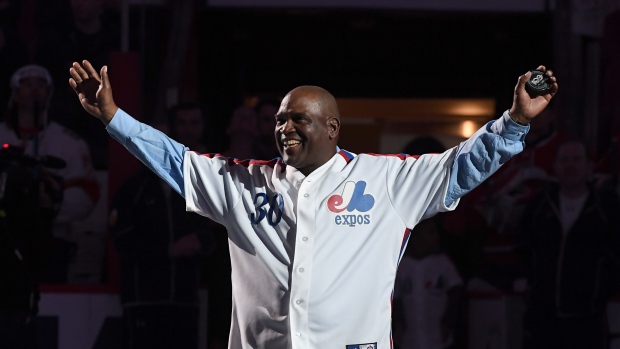

For the first chapter of his new memoir, Tim Raines chose one of the darkest chapter in his life. TSN.ca caught up with the Montreal Expos legend upon the release of Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball’s Fast Lane ahead of his July induction to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown

, TSN.ca Staff

For the first chapter of his memoirs, Tim Raines chose one of the darkest chapter in his life.

Raines, who will be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in July, opens Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball’s Fast Lane with the time he missed the beginning of an afternoon game with the New York Mets in May of 1982 because he was in the midst of a cocaine binge.

The Montreal Expos legend thought that rock bottom was an appropriate starting place for his story.

“I didn’t want people to feel like this was just going to be a totally feel-good type of book. My life wasn’t totally feel-good,” Raines told TSN.ca. “I think that getting it all out there early kinda makes people realize that, okay, this dude really did have problems when he started, but at the end, he’s a Hall of Famer. He went through some stuff and he had to deal with a lot of stuff getting to where he actually ended up. I thought it was important to do that first.”

Coming up with a way to start a book was something that the 23-year veteran never thought he would be doing.

“A lot of my other friends wrote books, but I never really thought about it,” Raines said. “Then all of a sudden somebody approached me and I said, ‘Sure, why not?’ At the time, I felt like it was the perfect time [for one] because it will come out right around spring training and I’ll already be [voted] into the Hall – I was going to get the votes – so, it was the perfect time to do this and that’s why I agreed to it.”

The experience of actually putting pen to paper (so to speak) and composing his life story was a surprising one for Raines and one in which he gained an appreciation for the undertaking.

“I didn’t know what it took to write a book,” Raines said. “When we [Raines wrote the book with Alan Maimon] got started, I thought, wow, this was a lot more intense than I thought. But then I started thinking if I’m going to write a book, this is how I’m going to do it.”

That meant tackling the uncomfortable issues in Raines’ past, namely his drug addiction – something that was completely out of character for Raines and the way he was raised.

“I never had any problems coming up through the minor leagues or through high school. I was an athlete and I was a serious athlete,” Raines explained. “I wasn’t a guy who went and partied with frat guys or partied all the time. I wasn’t that kind of guy. I was a guy who loved playing sports and I loved doing what I did. I wasn’t a partier and from a small town, so you didn’t have the bright lights [of a big city].”

For Raines, much of what got him started dabbling in drugs was a means to fit into his new environment as a Major League Baseball player.

“To fit in, you hang out with a crowd…you know, you think it’s the right crowd, but you just don’t know,” Raines said. “Then one thing led to another and then all of a sudden I’m caught in a situation where I’m like, what the hell am I doing?”

Cocaine quickly became a vice for Raines.

“I think the first time I tried [cocaine], I didn’t know anything about it,” Raines said. “I didn’t even know it existed, that’s how clean of a guy I was. I think I might have had a few drinks before. I tried to smoke cigarettes and that didn’t turn out too well. So I wasn’t into all that kind of stuff, but you get to Montreal and Montreal can be a party hard kind of town.”

Raines recalls an on-field incident that put into perspective just how far under the sway of the drug he really was.

“I actually remember taking a pitch that looked like it was going to hit me in the head and ducking away from it and the umpire called it a strike,” Raines remembered. “I was like, ‘The ball almost hit me!’ and he goes, ‘What the hell are you talking about? The ball’s right down the middle.’ And I’m thinking that he’s wrong and I’m right. So I look at the video and I’m all over the umpire and he’s right and I’m wrong. I’m hallucinating this stuff up here. Something is not right because I’m not used to not having control over what I do on the field. I’m starting to see things that aren’t really there. I didn’t think about it at the time, but obviously something was very wrong.”

That infamous May day in 1982 laid bare for the world what Raines had become.

“I kinda got caught up and then realized that something was wrong,” Raines said. “This is not me. This is not what I do. I mean, I’m going to miss a game. I’ve never missed a game. And that was when it all came out.”

Raines’ production dropped in 1982, his first full season in the majors. His OPS went from .829 to .723 and he managed only six more RBI in more than twice as many at-bats. But he remained an All-Star and managed to lead the National League in steals again that year with 71. There were no real outward indicators that he was using, yet Raines tried as best he could to conceal it.

“The whole time I went through it, I don’t think people realized I was doing it,” Raines said. “I tried to hide it as well as I could and, obviously, it must have been working because nobody came up to me to say anything about it, or maybe they were just [trying to be polite] and not tell me anything.”

Raines would subsequently meet with team president John McHale about his substance abuse and go to a rehab facility in Florida in the offseason. He truly believes that day at his nadir went a long way in not only saving his baseball career, but his life.

“The missing of the game, I think, was the best thing that ever happened because if I wouldn’t have missed that game, I’d probably have continued to try to fool people,” said Raines. “I probably could have killed myself one way or another.”

Looking back on it now, Raines attributes those days to a young man in over his head both personally and professionally.

“I was a kid and I had a kid,” Raines said. “I had a kid and I had just gotten married as a 20-year-old. It just happened very quickly. All of a sudden, I’m a big leaguer. I’m sure I wasn’t ready for marriage and I’m sure I wasn’t ready to have kids, take care of kids. That’s what we do. That’s what a man does. But I wasn’t a man at the time, so I think a lot of that played a big part in trying to have a young part in my life –to be able to not be married, to not have a kid.”

With his cocaine problems behind him, Raines went on to a Cooperstown-worthy career, but whether or not he would actually be enshrined was another matter.

In his first year on the Hall of Fame ballot in 2008, Raines received 24.3 per cent of the vote. By 2012, support had doubled to 48.7 per cent and rose to 52.2 the following year. Then in 2014, though, Raines’ vote fell down to 46.1 per cent and the chances of ever reaching the required 75 per cent and a Hall of Fame call looked bleak.

But thanks to some campaigning for his case in Montreal and elsewhere, the tide turned - Fifty-five per cent in 2015 and 69.8 per cent a year ago. Only then did Raines think Cooperstown could become reality.

“The only way it’s not going to happen is if I start to lose votes and last year I gained more votes than anybody on the ballot,” Raines said. “My momentum was going, so there was no way I couldn’t get 23 more votes. Twenty-three more votes is all I needed. If it doesn’t happen, then something is wrong with the voting system. But it was the first time in the 10 years that I felt comfortable – not totally, not 100 per-cent – maybe 80 per cent. But it’s gotta be safe. I thought okay, now we got a chance.”

With 86 per cent this past January, Raines was on his way to the Hall of Fame. But before July 30 comes, Raines will continue to promote Rock Solid, the story of a life he calls “kinda like a movie.”

“I wanted to tell the whole story – just the things I felt like could help someone, could let people know that it’s not just peaches and cream just because you’re a major league player,” Raines said of his book. “You’re gonna have good times, you’re gonna have bad times. It’s a rollercoaster ride, but at the end, you can still end up at the same spot you would have if none of that [bad] stuff had happened.”