Jun 30, 2017

TSN.ca's Canada 150: The Summit Series

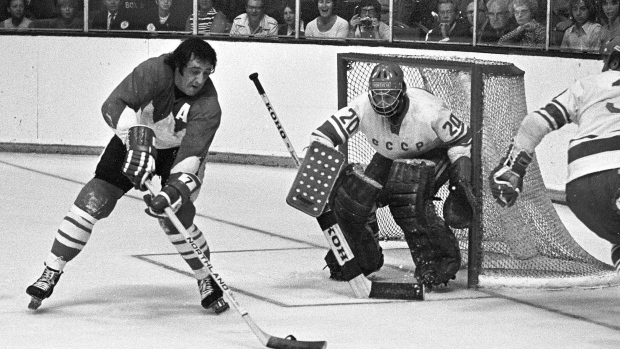

It’s hard to picture a Summit Series without Phil Esposito, yet that’s nearly what happened. The Hockey Hall of Famer looks back on the epic meeting and Canada and the Soviet Union in 1972.

, TSN.ca Staff

It’s hard to picture a Summit Series without Phil Esposito, yet that’s nearly what happened.

The now 75-year-old Hockey Hall of Famer wasn’t too keen on a tournament that would cut into the summer time he had earmarked for his hockey school.

But Canada wouldn’t take no for an answer from the Sault Ste. Marie, Ont., native.

“I got three calls,” Esposito recalled of the spring of 1972. “The first one was from [then NHLPA head Alan] Eagleson asking me to play and I said no. I don’t want to do that. I have my hockey school, my brother and I. They've already paid. What am I going to do, just give the money back to the kids? The second call I got was from [Esposito’s former Boston Bruins coach and Canada coach] Harry Sinden and I said no again.”

The third time proved to be the charm.

“I got a call from Bobby Orr,” Esposito said. “Bobby said, ‘Phil, I can’t play. My knee is really bad and we really need you to play.’” I said, ‘Robert, you’re my friend, you’re my teammate and you got it. I’ll do it.’ And that’s how that happened and my brother wasn’t very happy with me because he didn’t want to do this.”

Esposito says his skepticism over a best-of-eight exhibition series with the Soviet Union was shared by many of his teammates.

“There was nothing to gain,” Esposito said. “We had everything to lose and nothing to gain. Think about it. We trained for what, about a week? Come on! We’re an all-star team of 35 guys. We can’t play everybody and that’s what everybody was promised - that they would play. How are you going to do that? We were so ill-prepared. I don’t give a s**t what you’re doing in life. If you are not prepared for it, you’re not going to do well at it.”

The prevailing sentiment heading into training camp was that the Russian opposition wasn’t going to be particularly good.

“They said they were not very good and all this other stuff,” Esposito said of Canada’s scouting. “I don’t know; I never saw them play. They said they were not very good, they were this and that and then I found out who the scouts were: two scouts from the Toronto Maple Leafs. No wonder they ended up last all these years.”

At the camp, Esposito wondered why the team was even called Team Canada when so many Canadian stars would be absent. The NHL and Hockey Canada had an agreement in place that no player signed to the breakaway World Hockey Association would be considered for inclusion.

“I remember standing up and saying one thing, ‘Why are you calling us Team Canada?’ And they said because we are the Canadians and I said, ‘Where’s Gordie Howe, Bobby Hull, Davey Keon and Gerry Cheevers?’ and so forth who were playing in the WHA. We should have been called the NHL Team, not Team Canada.”

Internal hockey politics aside, the tournament was a go for September of 1972 and it didn’t take long for Canada to think they were in a mismatch.

Esposito scored just 30 seconds into Game 1 at the Montreal Forum on Sept. 2 before Paul Henderson doubled the lead six minutes later. Canada was cruising. But the bottom would fall out.

“We were up 2-0 and then we got a penalty and then we got another penalty,” Esposito recalled. “And they just started to turn it on. It was 94 degrees in Montreal that day; there wasn’t air-conditioning in the Forum and we were just not prepared. We weren’t in shape and were not ready. By the end of that first period, we were all saying, boy, we’re in trouble.”

The Soviets would tie the game up by the end of the first en route to a 7-3 victory. Canada was shell-shocked.

Two days later at Maple Leaf Gardens, Canada would square things up on goals from Esposito, Yvan Cournoyer, Frank Mahovlich and Peter Mahovlich on the way to a 4-1 victory. Esposito praises his brother Tony for his stabilizing performance in the Canadian net that game.

“My brother in the first period, I think had only eight or nine shots, but five of them were breakaways,” Esposito said. “He was sensational. Tony played side-to-side. Russia went side-to-side and Kenny [Dryden] was a straight up-and-down goalie. That’s why Kenny struggled a little bit [in Game 1], but then Kenny came through in the last game, Game 8. He came through big time for us and that’s because he was a great goalie.”

Game 3 in Winnipeg saw a 4-4 tie with Canada blowing both a 3-1 and a 4-2 lead. Heading to Vancouver for Game 4, the Canadian fans became restless.

“There was booing the whole time,” Esposito recalled. “They booed the s**t out of us.”

Esposito wasn’t happy with Sinden and assistant coach John Ferguson’s constant lineup changes.

“I thought about this over the years,” Esposito said. “Game 4 in Vancouver, again we changed lineups. The Toronto lineup, we won. We go to Winnipeg and we change lineups again and go to Vancouver and change lineups again. How are you going to become a team if you keep changing players all the time? Quite frankly, I remember talking with Harry and Fergie saying, ‘Listen, I don’t care who you pick, but you’ve got to pick 20 guys here and let us play because you can’t keep doing this.’ You cannot keep putting guys in and guys out and I know everybody got promised, but if we want to win, we have got to become a team.”

Canada got off to a disastrous start in Game 4 when the Soviets converted on the power play twice on penalties to Bill Goldsworthy to lead 2-0 after the first period on the way to a 5-3 victory.

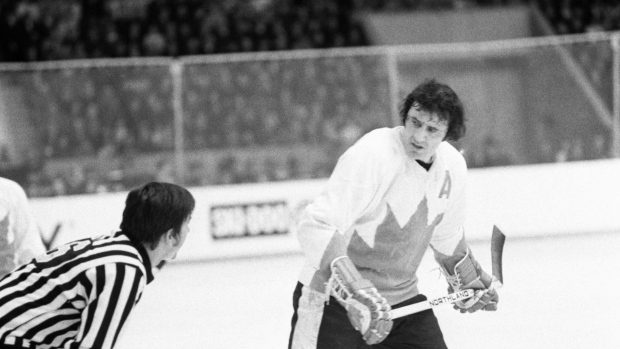

The indelible memory for Canadians from Game 4 would be Esposito’s fiery postgame interview with Johnny Esaw.

“To the people across Canada, we tried, we gave it our best, and to the people that boo us, geez, I'm really, all of us guys are really disheartened and we're disillusioned, and we're disappointed at some of the people,” Esposito said into the camera. “We cannot believe the bad press we've got, the booing we've gotten in our own buildings. If the Russians boo their players, the fans ... Russians boo their players ... Some of the Canadian fans—I'm not saying all of them, some of them booed us, then I'll come back and I'll apologize to each one of the Canadians, but I don't think they will. I'm really, really ... I'm really disappointed. I am completely disappointed. I cannot believe it.

“Some of our guys are really, really down in the dumps, we know, we're trying like hell. I mean, we're doing the best we can, and they got a good team, and let's face facts. But it doesn't mean that we're not giving it our 150 per cent, because we certainly are. I mean, the more – every one of us guys, 35 guys that came out and played for Team Canada. We did it because we love our country, and not for any other reason, no other reason. They can throw the money, uh, for the pension fund out the window. They can throw anything they want out the window. We came because we love Canada. And even though we play in the United States, and we earn money in the United States, Canada is still our home, and that's the only reason we come. And I don't think it's fair that we should be booed.”

Esposito says he didn’t watch that famous interview for a decade.

“I never saw what I said for 10 years – 1982 was the first time I saw what everyone saw when Johnny Esaw interviewed me,” Esposito said. “And when I was going on the ice to shake hands with Johnny and also with Boris Mikhailov, there were these three or four kids – they were maybe in their 20s, probably, maybe early 30s. They were just yelling obscenities saying, communism was better and all this s**t and that just got me because communism isn’t better.”

Things weren’t much better for Canada after the game.

“I felt so sorry for a guy like Billy Goldsworthy,” Esposito said. “In fact, I felt so bad I got scared for him. I did. He was in such a state of depression because he got [those] penalties. He was in such a state of depression, I thought, holy cripes. We took [Goldsworthy] - Wayne [Cashman] and I and Paul [Henderson] and J.P. Parise – and we all went to a hotel bar. I think it was the Hotel Vancouver. We were sitting there trying to console Goldie and it was really scary, man. It was really scary. There were people in the bar calling us names and we had to get out of there or there would have been a big fight.”

Getting out of Canada during the two-week break between Games 4 and 5 seemed to do the trick for Canada, as they traveled to Stockholm for exhibitions with the Swedish national team.

“We became a team in Sweden,” Esposito recalled. “That’s when we became a team.”

But Game 5 brought with it another blown lead.

Canada held a 3-0 lead by the middle of the second on goals from Parise, Bobby Clarke and Henderson. They appeared to be in control until a late onslaught from the Soviets with four goals in the game’s final 11 minutes led to a 5-4 loss.

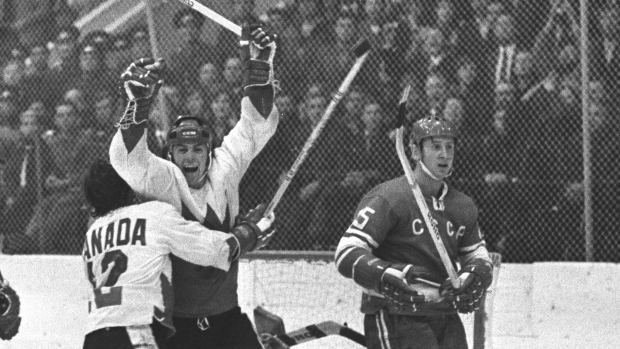

Down 3-1 in the series, Canada mounted a comeback to make Game 8 for all the marbles.

Three goals in the second period of Game 6 from Dennis Hull, Cournoyer and Henderson lifted Canada to a 3-2 victory. In Game 7, Henderson scored with a little over two minutes remaining to even the series at 3-3 in a 5-4 victory.

What happened in Game 8 is etched in the Canadian consciousness for eternity. Canadians – even those who weren’t even born in 1972 – remember Foster Hewitt’s call of Henderson’s game-winning goal by rote.

But what is lost in the madness of that final minute is Esposito’s game on the whole. In Game 8, Esposito became the only player on either team to register four points. It very well could have been the finest performance in his storied career.

“I don’t know; I really don’t know,” Esposito said. “I know one thing: I played a lot and the more I played in my life - no matter where I was - the more I played, the better I played and I knew it and I felt it. I am not just saying that. Somebody told us the other day a lot of guys play 18, 20 minutes and they’re dead. I averaged close to 37-38 minutes a game and Bobby Orr did over 40 minutes a game because we only had five defencemen and three lines.”

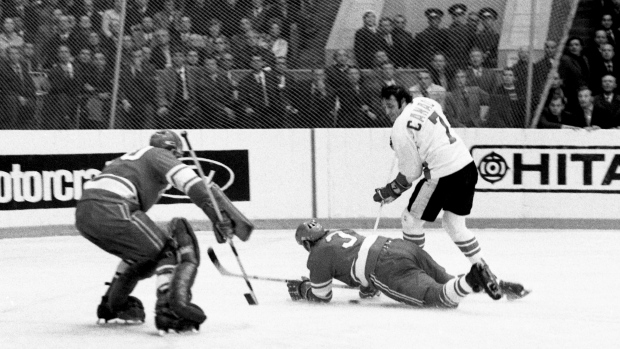

On the series-winning goal, Esposito stayed out for a double shift.

“I stayed on,” Esposito said. “I wasn’t coming off until we scored. I just wasn’t coming off.”

Call it a premonition.

“I felt that we could score,” Esposito said. “Paul did the same. He called Peter Mahovlich off. He was yelling at him and I asked Paul after. I said, ‘How come?’ and he said, ‘Phil, I just had this feeling.’ I don’t know what you call that, but I’ve had it before myself in games where I just know that I can do this. I can do this and I want to be on the ice. Paul had that feeling.”

Still, Esposito believes Canada was aided by a bit of serendipitous luck, when Henderson fell over the stick of defenceman Valeri Vasiliev.

“If Paul doesn’t fall behind the net, the goal doesn’t [happen],” Esposito said. “Because why – on an easy shot – would [Soviet goalie Vladislav] Tretiak, on an easy shot from me – I was going backwards and shot it forwards – kick that rebound straight out? It’s amazing – right on Paul’s stick.”

Looking back on the series nearly 45 years later, Esposito believes that the players on both teams were made into pawns by a pair of governments trying to score political points by attaining supremacy on the ice.

“This was supposed to be an exhibition series that turned into a political football and the Russian players and our players, the Canadian players, were the football and I blame both governments,” Esposito says. “They made it into a political thing and as far as I was concerned, it was society against society; capitalism against communism and that’s what I believe. A lot of guys didn’t think that way, but I did. That’s what I felt. I said this before: To me, it was a war. We were at war with these guys and this was our battlefield right here on the ice.”

Though Esposito still remembers the series fondly and is happy to be a part of such a momentous occasion in Canadian sports history, he can’t help but have one question about it that still lingers.

“I always think – and I don’t mean to be a negative person, but what would have happened if we had lost?” Esposito said. “Me? Nobody gave a damn about it in Boston. Nobody cared about it in Chicago with my brother or in New York. They didn’t, but what about the guys who played in Montreal and the guys who played in Toronto?”

Fortunately for Canadians, that question will forever remain theoretical.