Feb 28, 2022

Panthers’ assistant GM Peterson on being a role model and making hockey more accessible

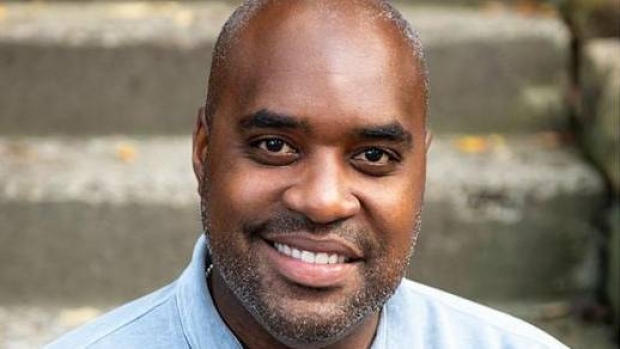

In November 2020, the Florida Panthers named Brett Peterson their assistant general manager. He is believed to be the first Black assistant GM in National Hockey League history. As part of Black History Month, TSN spoke with Peterson about his path to the Panthers’ front office and the sport's diversity efforts.

By Salim Valji

In November 2020, the Florida Panthers named Brett Peterson their assistant general manager. He is believed to be the first Black assistant GM in National Hockey League history.

Peterson, a Northborough, Mass., native, was a defenceman for Boston College and won the 2001 NCAA national championship. After going undrafted, he had a five-year professional hockey career in the AHL and ECHL.

He then became a player agent with Acme Sports and represented Boston Bruins goaltender Tuukka Rask. He eventually became the vice-president of hockey for Wasserman Media Group.

As part of Black History Month, TSN spoke with Peterson about his path to the Panthers’ front office and the sport's diversity efforts.

How did you get started in hockey? What was your introduction to the sport?

“I was introduced basically by necessity from my parents. I had a bunch of energy when I was a kid and my mother tutored hockey players. For part of her payment for tutoring hockey players, the college hockey coach at the time was nice enough to put me on the ice and teach me how to skate. That’s how I got thrown into the sport. We didn’t have a [hockey] background as a family, so I got thrown into it that way and fell in love with it from there.”

Who was that college coach?

“At the time, we were living in Albany, New York, and then we moved to Massachusetts, so I learned to skate at a college, RPI [Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute], in Troy, New York. The coach at the time was a gentleman named Mike Adessa, who actually subsequently was a scout for a long time with the Flames.”

As you were going through your hockey journey, who were your role models? Who were the players or people you looked up to?

“I used to go to a lot of college hockey games when I was a kid. I started there and my love for the game really flourished. At the time, there was players like Bruce Coles and Graeme Townshend and Joe Juneau, guys that I really admired the way they played. When we moved to the Boston area, obviously you get fully immersed in hockey culture. From there, there were many different guys, whether it be Ray Bourque or Cam Neely, guys that I would watch as a kid. Hockey was such a big neighbourhood activity back then, so you emulated all these guys when we were playing outside and street hockey and on peoples’ ponds or makeshift rinks.”

Did you find it challenging when you are a visible minority in the sport? Did you experience any racism and how was it when you might be the only player of colour on a team?

“For sure I experienced it when I was going through youth hockey and junior hockey. It’s hard for me to really think that it was a huge deterrent in my upbringing because, in some regard, it made me who I am today, going through some of those processes and instances as a young boy. What I really try to do right now is highlight. I think sometimes we focus too much on the isolated, smaller events where racism and issues of social economic background come up, and I think I try to highlight so many of the good people that helped me along the way.

I’d say the vast majority that didn’t look like me were people that allowed me to climb the ladder. There are a lot of things I try to highlight in terms of getting people that aren’t fully immersed in hockey to understand who really are [the people in] hockey. Yes, not everyone in hockey looks like me but it is getting a lot better and more diverse. At the same time, even when it wasn’t as diverse as it is now, it was a lot of fantastic and wonderful people who went out of their way to support me along my journey.”

Who are those people and how did they help you out?

“There’s so many, but a couple are Mike Adessa and Jerry York. Jerry’s obviously a legendary figure in the game that didn’t have to go and recruit me to Boston College and give me that platform and winning a national championship and then continuing to support me in my professional career afterwards. Certainly Bill Zito, who is probably one of the biggest champions for me in getting me in different careers and teaching me and guiding me along the path. My coach, Steve Jacobs, he was a guy that when I went to a prep school that had never really seen anyone like me go through there, he put me in situations to play huge minutes with tremendous hockey players and allowed me a path to college hockey. There were different parents of players I played with that would drive me to and from and help with the payments and stuff like that for hockey. Just countless people, but there’s going to be a lot of people that have played such a major role in me getting me here that I’d have to sit here all day and go name by name.”

What has the Panthers organization done and how do they approach diversity and trying to make hockey more accessible?

“I think the way we approach it is that we look at people. We look at talent. We want the best people. We want the most talented people that want to collaborate and work together. Some people walk through the door and see a Black man or a woman, or an Asian man or woman, we just see, “What can you do to help us?” That’s I think the way the world is heading and how it always should be – get the right people no matter what they look like and where they come from and help us be better.”

Hockey has made strides recently. What more can the sport do to be more diverse? What are the next steps?

“I think it starts at the very top. If you want to make these changes, you can make them. I think from the leadership down, especially with us at the Panthers and ownership, what they have done in stepping out in front and being ahead in these diversity panels and going above and beyond to be inclusive and support, I think it starts from the top down.

“Obviously [NHL executive vice-president of social impact] Kim Davis has done a tremendous job and I applaud the NHL for helping her along her way, commissioner [Gary] Bettman and [deputy commissioner Bill] Daly. We’re heading in the right direction. These things don’t happen overnight. I don’t want it to be just, ‘Let’s get people in here because we’re short on numbers.’ I want to start including people at the lower levels so that naturally, just like me, organically, they get to these higher seats. Not because they were handpicked, but because they did the work and wanted to get here. That starts all the way down at youth hockey and getting more diverse people involved in the game so they can flourish and someday they get to the point where they can share their gifts with us as well.”

Is it tricky to balance being a role model versus simply just doing your job?

“I’m just being myself. I think I’ve gone in and out of a lot of different circles and the one thing I’ve always been steadfast is that I am who I am. I allow myself to be who I am and grow. Situations come up and we deal with them one thing at a time. It’s not really that overwhelming because you’re just yourself.”

What do you hope to accomplish in your NHL front office career?

“Obviously, we always want to get to the highest level. I wanted to get here and wasn’t able to get here as a player, and I’m now trying to get to that highest level I can as an executive. My main focus right now is being the best assistant general manager as I can for the Florida Panthers. I think if I do that, I’m not too focused on what’s ahead or in front of us. When you look too far down the road, you often trip and fall. Right now, we’re focused on right here and right now and two big games this week and we’ll see what happens from there.”