Aug 5, 2021

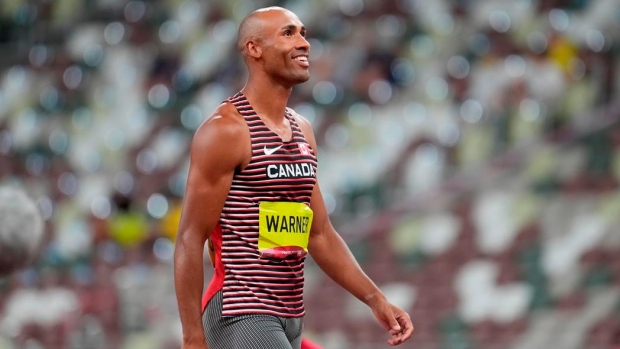

What it took Canada's Warner to win the decathlon

Dr. Lisa Fischer watched in awe this week as Damian Warner gracefully leapt over hurdles, sprinted past competitors and vaulted his body over a pole nearly five metres off the ground.

The Canadian Press

Dr. Lisa Fischer watched in awe this week as Damian Warner gracefully leapt over hurdles, sprinted past competitors and vaulted his body over a pole nearly five metres off the ground.

Seeing an athlete excel at one Olympic sport is impressive enough, but a gold medal in the 10-discipline decathlon is special, she said.

Warner, a 31-year-old from London, Ont., set an Olympic decathlon record with 9,018 points, including personal bests along the way, to win gold at the Tokyo Games on Thursday after two exhausting days of competition.

Some, including Fischer, have described the decathlon as the "toughest Olympic event" because of the number of disciplines involved and the toll it takes on competitors, both physically and mentally.

So what does an athlete need to have decathlon success on the Olympic stage?

Fischer, a sports medicine director at the Fowler Kennedy Clinic and an assistant professor at Western University who's worked with Warner for eight years, said decathletes require specific qualities — strength, speed, co-ordination, balance — and while some of those are there to start with, a staff of coaches, physiotherapists and nutritionists need to coax their development.

"It's like taking out a Lamborghini and learning how to drive it properly," she said from London, Ont. "Every part of your physical being has to be fine-tuned and conditioned."

While most athletes spend hours training in one specific discipline, multievent competitors like decathletes and heptathletes require a more well-rounded approach.

Jessica Zelinka, a former Olympic heptathlete from London, Ont., who's now a coach and consultant in Calgary, said combined-event athletes tend to focus on their strengths first, then attempt to improve on their weaker disciplines.

It can be tough to find the right balance though, Zelinka said, and tougher for some to realize they'll likely never win all 10 events in a single competition.

Warner won just three in Tokyo — the 100 metres, long jump and hurdles — but performed well enough in the other seven to secure his Olympic title.

Zelinka said the way he dominated his three winning events made the overall first-place finish more impressive. Warner's 100-metre time of 10.12 seconds would have qualified him for the 100-metre final, while his 8.24-metre long jump would have won him the bronze medal in the stand-alone long jump event.

"You need speed and power and timing and coordination to the ultimate level because everything is measured by the millisecond and the centimetre," Zelinka said. "But not every athlete can do that, even if they're fast and powerful.

"It takes a lot of skill and really good coaching, and also a lot of maintenance."

Zelinka, whose brother-in-law is a physiotherapist on Warner's team in Tokyo, said she watched most of Warner's events from her Calgary home, including the final 1,500-metre race on Thursday morning.

As most of the athletes stumbled to the ground in exhaustion after crossing the finish line, Zelinka could relate to their physical anguish, thinking back on her own experience finishing seventh at the London Olympics in 2012.

"I didn't lie on the track because I didn't want to have to get myself back up," Zelinka said with a laugh.

"It was a bit different for me because I was disappointed, but there's a sense of relief for sure. There's a lot of built-up tension before that last event.... You're dreading it (before it starts) but then it's like: 'That was amazing. Let's do this again.'"

Brianne Theisen-Eaton, the 2016 Olympic heptathlon bronze medallist, said the end of a big competition is "one of the best feelings you can experience in your life."

But while multidiscipline sports are physically taxing, they can also take a mental toll on competitors, Theisen-Eaton added.

A tough result in one of the disciplines can send athletes into a tailspin while they wait for the next event to start, and external factors like weather and scheduling can also mess with performance.

"It's super long days and (Tokyo) was exceptionally hot," Theisen-Eaton said. "So for (Warner) to keep his head in the game and stay composed ... I mean it just shows the level of athlete he is."

Theisen-Eaton of Humboldt, Sask., retired from competition in 2017, but she and husband Ashton Eaton, the 2016 Olympic decathlon champion, woke up early each morning in Portland, Ore., to watch Warner in Tokyo.

Eaton held the Olympic record, set in Rio five years ago, before Warner beat it. But Theisen-Eaton said there was no disappointment in their household.

"Ashton was jumping up and down and was so excited for him," she said. "He's a big believer in pushing these records and making them better for the next generation."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 5, 2021.