ALLAN, Sask. — Rance Cardinal walked 1,200 rain- and snow-soaked kilometres from Sioux Lookout, Ont., to Saskatchewan last spring to deliver a handmade Humboldt Strong sign.

That’s exactly what Cardinal delivered – a sign to the Schatz family from their son Logan, the Broncos’ captain who was killed in last April’s bus crash.

Humboldt opened its arms for Cardinal on May 27 at the finish line of the 48-day trek for hockey’s Terry Fox. Kelly and Bonnie Schatz drove up to Humboldt for the welcoming party.

To mark his healing journey, Cardinal gave each family vase decorated in Broncos green and gold.

Inscribed on it was a simple phrase: “If a cardinal should appear, a loved one came to bring you cheer, a memory, a smile, and a tear.”

Bonnie sighed. “I said to Kelly, ‘Well, we’re never going to see a cardinal in Saskatchewan’,” she said.

The Schatzs used the trip to Humboldt pick up Logan’s belongings from his longtime billet family’s house, the Brochus.

Among the things Kelly and Bonnie collected from the Brochus that day was Logan’s wallet. Logan’s black, cracked-leather billfold was thick with stuff. He kept the business card of every college coach who had ever contacted him inside. Bonnie opened it.

The very first card on top of the pile was from Saint Mary’s University of Minnesota - home of the Cardinals.

“You have to believe in some of this,” Kelly said.

“I was like, ‘Okay,’ ” Bonnie said, still shaking her head nearly a year later. “I have to believe in all these little signs.”

They haven’t been hard to find. Two cards beneath the Cardinals was Logan’s organ donor card, which he had already signed in anticipation of his 21st birthday on Sept. 16, which to this day sends a shiver down Bonnie’s spine when she thinks of the Logan Boulet Effect.

Her son's No. 20 seems to show up everywhere Bonnie looks. She was assigned Row 20 on a recent flight to Arizona. She went back to Humboldt for the Saskatchewan Roughriders’ practice there. Amid of a throng of people, there was just one small opening to watch practice. Bonnie looked down and saw it was the 20-yard line.

He is never too far from mind or sight. Every member of the Schatz family got matching “LS❤️20” tattoos on their forearm. Bonnie wears two necklaces, one with Logan’s signature on the pendant, another with his fingerprint.

Logan is the first thing you see when you sit down at the Schatz’s kitchen table. Logan’s ashes rest in a wooden box – one that he actually made himself in a high school woodworking class – on top of an electric fireplace in the family living room. There is a cemetery at the end of their street, but even that felt too far.

“We wanted to keep him close by,” Kelly said.

The truth is, Logan Schatz is omnipresent - from the rink here in his hometown of Allan that now bears his name, to the countless ‘Schatzy Stories’ that Bonnie receives in her Facebook inbox from complete strangers, to the bar he set on the ice in Humboldt with a legacy that lives on in the form of trophies, scholarships and tournaments named after him.

One year on from the tragedy that claimed the lives of 15 others and forever changed the lives of 13 more, the Schatz family grapples daily with the absence of Logan’s contagious laugh, his competitive fire, his ‘old soul’ maturity and his warmth.

They sometimes ask why. The best they can figure is heaven needed a captain, too.

Set in the shadow of the local Nutrien potash mine, Allan (population: 704) is quintessential small-town Saskatchewan.

“If you’re driving too fast, you might miss it,” said former Ottawa Senators defenceman Jared Cowen of his hometown.

The town’s slogan is “City Convenience, Country Charm,” a nod to the fact Allan is just 35 clicks southeast of Saskatoon. There is a Co-Op convenience store and gas pump, a four-lane bowling alley, a K-12 school, an outdoor swimming pool and two or three small eateries - depending on the day.

Allan’s iconic Saskatchewan Wheat Pool grain elevators were demolished in 2014. It’s quiet, simple and a mostly idyllic place to raise a family.

“There was always lots to do and nothing to do, if that makes any sense,” Cowen said. "I loved playing outside, so it was perfect for me.”

The epicentre of Allan, as in so many other hamlets across Western Canada, is its' sports complex. The Allan and District Communiplex squeezes in a smaller-than-regulation rink (190 x 85) next to a four-sheet curling centre. Outside there are baseball diamonds and a modest nine-hole municipal golf course with sand greens. Just three bucks will get you a round.

With five kids sprinkled over an even 10 years, there was always something going on in the Schatz household - located five blocks from the rink. Logan was the baby of the family, behind sisters Courtney, Kayla, Meagan and big brother Brandon, who is six years Logan’s senior.

Cowen grew up playing with Brandon on the Allan Jr. Flames, a team co-coached by Kelly. His walk to the Schatz’s house was “maybe 15 seconds.”

“Between my house and their house was an empty lot," Cowen said. "I could always see when they were playing outside, so I was at their house all the time.”

Cowen is one of two Allan native sons to skate in the NHL. Willie Brossart, who played 129 games for Philadelphia, Toronto and Washington in the early 1970s, is the other.

Cowen moved to Saskatoon at the age of 14 to pursue hockey and is now back there after being bought out by the Maple Leafs in 2016. When hearing about the Broncos’ bus accident on April 6, 2018, Cowen immediately went online and scrolled through the roster to see who he knew.

Six degrees of separation don’t exist in Saskatchewan.

His eyes stopped at the name of the little boy who always wanted to tag along with his big brother and best pal.

“It was surreal finding out,” Cowen said. “Heartbreaking.”

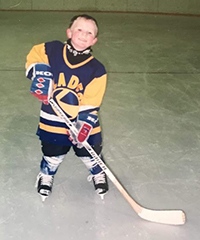

Logan was on the ice by age three. Kelly was the caretaker of the Allan rink and one of the perks was a set of keys that allowed him access to extra ice time for Logan when the schedule allowed.

He excelled at almost every sport or activity he tried. Golf. Volleyball. He collected provincial medals in track and field. Even dance. Logan took three years of hip-hop classes.

“And he was good at it!” Bonnie said. “We would watch his moves. He had attitude.”

When Logan started at Stars on Stage in Allan at age 9, he was the only boy in the class, which included his older sister, Meagan. The next year there were four boys. It doubled to eight boys in his third year.

He continued to be a trendsetter as a young man. He wore a blue bow-tie to his sister’s wedding in 2015, then continued to wear it to Broncos games. That photo with his bow-tie was so widely circulated in the media that many thought he owned a whole collection. There was just that one. Now, kids playing minor hockey in Allan have been spotted wearing bow-ties when they get dressed up for playoff games.

Logan was the captain of nearly every team he ever played on. On the ice, he was the six-year-old who would repeatedly set up teammates so they could score their first goals. Off the ice, he was one of the first to befriend an autistic classmate.

“He was just a very friendly, friendly kid,” Bonnie said. “And mature.”

And perceptive. In Peewee, he tried out for a team in nearby Martensville, a step up to the “AA” level and a step up in fees. Kelly worked in maintenance at the Cargill crushing plant near Clavet and Bonnie was an educational assistant in Colonsay. Funds were not unlimited and Logan knew it.

“I took him to tryouts and he came back and said ‘No, I don’t want to play there,’” Bonnie said. “I said, ‘I hope it’s not what you overheard me saying to Dad, because we’ll make it work if that’s where you want to play.’ He said, ‘Nope, I’m good. I don’t like the coach.’ I think he was making that up.”

By age 14, Logan caught the eye of the Kootenay Ice, who selected him in the ninth round (186th overall) of the Western Hockey League’s Bantam Draft.

That’s when he made his way to Midget AAA, moving 150 kilometres away at age of 16 to play for the Beardy’s Blackhawks in the Saskatchewan Midget Hockey League. He billeted with one of Bonnie’s nieces nearby, which put his mom’s mind at ease.

Kelly worked Monday through Thursday at the plant. On Fridays, he would pick up Logan and take him another 150 kilometres to practice with the Humboldt Broncos, who had listed him as an affiliate.

“He said, you know, ‘I feel like I’m out of place here [in Humboldt],’” Kelly said. “I said, ‘Just keep going.’”

In March, 2014, Logan came walking out of Elgar Petersen Arena with a green helmet, a couple sticks and a pair of gloves. He told his dad: “I’m playing tomorrow.”

Logan’s debut was the final Saskatchewan Junior Hockey League regular-season game on the Broncos’ schedule. He collected three assists, beginning one of the all-time great careers in the 50-year history of the Humboldt Broncos.

Logan ranks first in franchise history in assists (157), fourth in points (207) and sixth in games (209).

“He’s the most dedicated player I’ve ever played with,” said former line-mate Chris Van Os-Shaw, who attended development camp with the Maple Leafs and now plays for Minnesota State Mankato. “It was hockey first for that guy. He loved it. He was the guy that would get that extra workout in. He really wanted to get to the next level.”

Kootenay attempted to sign him as an 18-year-old, but Kelly said his son had his sights set on school. His intensity was always on display, even before he became Humboldt’s captain.

“We lost a lot of games in 2015-16, traded away a lot of 20-year-olds before Christmas,” said Michael Korol, Logan’s billet roommate in Humboldt and one of his closest friends. “One practice we were just trying to get it back on track. We did this bear pit drill in the corner, just a one-on-one battle drill.

“We’re watching the drill and the next thing I know, I hear a whistle. Logan Boulet and Schatzy dropped the gloves and were just going at it. That was Logan. He wanted to win more than anyone. I think the best part about Logan was that what happened on the ice, stayed on the ice.”

Logan already had a full SJHL season under his belt by the time Darcy Haugan took over as the Broncos’ coach and general manager in 2015. One of Haugan’s first requests for his team of new faces was for help to move him and his family into their house.

Logan was among the first to show up. He rallied others to join, including Korol, in a move that left a strong first impression on his new coach.

When it came time to name a new captain after Anthony Kapelke was traded and Corey Dambrauskas went down with a career-ending injury, Haugan turned to Logan.

“You never see an 18-year-old captain in the SJHL,” said then-Broncos assistant coach Chris Beaudry. “To see a captain for two and a half seasons in one place is rare. It’s very rare.”

Haugan’s respect for Logan was shown in the way he valued his opinion – both on and off the ice. One practice, Beaudry said Logan stopped a drill and challenged Haugan because he wasn’t onboard with the coach’s point. Haugan halted practice for 15 minutes and explained it until everyone was on the same page.

“He was almost an assistant GM,” Beaudry said. “If we were going to make a move, [Darcy would] ask him - especially any trade in the league, what he thought of the move and the player. We really valued his opinion. Darcy would say all the time, ‘I’ve hitched my wagon to this horse. We’re riding him all the way. This is his team.’ ”

They had a level of trust that no other Broncos player managed. Those conversations were kept confidential. Logan was instrumental in the trades to acquire Nick Shumlanski from Flin Flon and Bryce Fiske from La Ronge last season. Shumlanski was his former billet roommate with Beardy’s and he played spring hockey previously with Fiske. He vouched for them. Both players survived the crash and played Canadian university hockey this season.

“One day, Darcy told Logan, ‘It’s kind of fun being a GM, ain’t it?” Kelly said.

Korol and Van Os-Shaw both said it was a coach-captain relationship they haven’t seen replicated on any other team. They called him a “second coach” who was intense and could sometimes yell more than Haugan. It takes a special player to be able to bark at his teenage teammates and not lose them.

“As a player and person, everyone in the league respected his game,” Van Os-Shaw said. “He was the most vocal guy. He liked to chirp and just laugh. He was someone you just wanted to be around. If you were upset or pissed off, he’d find a way to talk to you.”

Korol, who now plays NCAA Div. III hockey at Norwich University in Vermont said “Logan was the loudest guy in the room, but in a good way,” Korol said. “He had a personality that could like up an entire room. It was just infectious.”

Korol said Logan was the “life of the party.” Logan was the beer pong champion of the Broncos.

Being captain of the Broncos in Humboldt came with certain responsibilities. Even if the boys wanted to have fun on a night that Haugan gave the “green light” to party, he was cautious of his reputation in town. So last February, he called Bonnie and made a request.

“He said, ‘Mom, can you stop and get me some Fireball and bring it to the game?’ I said, ‘Logan, you’re old enough to go and get your own liquor now,’” Bonnie recalled.

“He said, ‘Well, I’m already in my suit, we’ve got a game and I can’t show up at the liquor board store. It won’t look good for the team, because they know who I am.’ ”

Logan lived Haugan’s “Core Covenant” that was plastered on the wall of their dressing room. He was honest, he worked hard and he put others first. The mother of one former Broncos player messaged Bonnie after the accident to share that their son was so homesick he was going to quit hockey if it weren't for Logan. The captain kept him playing.

Brayden Camrud was one of the three players from the accident who returned to play this season. He called Logan “one of the most influential figures in my life.”

“His main goal at the end of the day was that we were a family,” Camrud said. “He ensured that everybody felt a part of the team. He never left anybody out. If you had a bad shift, a bad game, a bad day – he knew. He’d be the first guy to step up and say, ‘Do you need someone to talk to?’"

When Nathan Oystrick was hired last summer as the Broncos’ new coach, one of his first decisions in training camp was to not name a captain out of respect for Logan.

“He didn’t get to finish the job last year,” said fellow returnee Derek Patter.

Camrud and Patter were named alternates along with newcomer Michael Clarke.

To Camrud, that was the right decision: “He was such an amazing person and captain that you wouldn’t want anyone else. You’d want him. Every team has got that guy and he was ours.”

Humboldt is an hour’s drive from Allan, so Kelly and Bonnie rarely missed a game – at home or on the road.

They were en route to Nipawin on April 6 when they got a frantic call from Layne Matechuk’s mom and were told about the accident.

“We heard it was bad, so we went straight to the hospital in Tisdale,” Kelly said. “We sat there trying to find some sort of information. So much was happening, we heard all of these different names being treated. Logan’s name never came up.

“That’s when I kind of had a good idea… ,” his voice trailing off.

There is one question the Schatz family has never been able to ask. By hockey tradition, the back of the bus – especially the one row with three seats near the bathroom – is generally reserved for a team’s most senior members and leadership group.

The people most severely impacted on the Broncos’ bus were largely seated toward the front, with coaches like Haugan and Mark Cross sitting near athletic therapist Dayna Brons, broadcaster Tyler Bieber and statistician Brody Hinz.

Where was Logan sitting?

It’s a question Kelly and Bonnie would rather remain unanswered.

“I’m sure that the boys could have told us,” Bonnie said. “We never asked.”

“You know, I like to think that Logan was sitting up front meeting with Darcy about the game,” Kelly said. “I don’t know what good it would do to know.”

Last spring, rising country musician Brock Andrews played a gig as a fundraiser for the Schatzs at a local tavern just up the road from Allan in Bradwell.

He arrived with a guitar just the right shade of Humboldt green, decked out with gold and black decals honouring Logan with “LS 20” and “We are all Humboldt Broncos.”

The guitar caught the eye of Kelly, who played from time to time himself, but Andrews toured with it for most of the summer. Scott and Laurie Thomas, who lost their son Evan in the crash, just happened to be at another show in August where Andrews was auctioning off that guitar for charity.

Knowing how much that guitar meant to Kelly, Laurie sent a text to Bonnie encouraging them to place a bid.

“We didn’t know how much it would go for,” Bonnie said.

Laurie responded: “Don’t worry, we’ll get it for you. It’s yours. We’ll make sure you get it.”

Laurie came through acting as Bonnie’s proxy – but Andrews and his show’s sponsor quickly recognized who it was for and wouldn’t accept a nickel.

With his new guitar in hand, Kelly rewrote the lyrics to Bob Dylan’s iconic “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door” in a tribute to the 16 people who died.

He said he struggled to find the right words, a process that proved therapeutic, and they finally came to him one day while at work. It all fit together. Kelly found a way to incorporate all 16 into the song.

Kelly played the spine-tingling tune at a barbecue for all of the Broncos’ parents at Kurt Leicht’s house in Humboldt on Aug. 24.

“Yeah, that was a tough one to get through,” Kelly said.

Those listening at the Leicht’s house that night said there wasn’t a dry eye in the room as Kelly poured his soul into the performance.

“Well, to be fair, it doesn’t take much to get us in tears,” Bonnie said.

More than 150 people, nearly a quarter of the Allan’s population, came out for the dedication of Logan Schatz Memorial Arena on March 16. Kelly and Bonnie said they were overwhelmed by the support, which included other Broncos families.

Bonnie originally did not want to give up two of Logan’s game-used sticks until she saw them hung on the wall.

“We didn’t think this would be this big,” Bonnie said. “They did an amazing job. Everything is beautiful.”

In the same lobby where Cowen’s Ottawa Senators and Spokane Chiefs jerseys hang, there are six posters of Logan, with photos from his time playing for the Allan Jr. Flames through to the Broncos.

Kelly’s favourite part, though, is visiting Schatzy’s Corner.

Tucked into a corner of the rink, Kelly made a ball hockey rink for kids to enjoy. Ball hockey was big part of Logan's life, he represented Canada internationally. Kelly planned, fabricated and completed the entire project – from the custom dasher boards and glass, to the rubber floor with plastic cutouts for the crease and red lines, to the nets that magnetically connect to the floor. It is a five-year-old’s Rink of Dreams.

Bonnie decorated the space with logos of each of the teams Logan played for and found the words to tell Logan’s story on a dedication plaque that sits nearby.

As the parents of the Broncos’ captain would, they insisted that Schatzy’s Corner - and the banner that hangs above the scorer’s table across the ice - honours not just Logan, but also the memory of the 15 others who died and the 13 survivors.

“We are not alone in this,” Bonnie said. “We have all leaned on each other.”

Building Schatzy’s Corner was a labour of love, a welcomed distraction, something Kelly could get lost in for hours after work.

“The hard part now will be finding the next project,” said Bonnie. “This has been both the shortest and the longest year ever. It seems like forever since we’ve seen Logan. But it’s so fresh, it feels like it just happened yesterday, too. I still expect him to walk through the door.”

Kelly will sometimes sit alone in the stands on weekend mornings and just watch. He feels at peace in the rink. Some days, he said, are better than others – a stark reminder that grief is not linear.

“I will sit up here and have a coffee. Sometimes people will come talk to me, other times they don’t bother me,” Kelly said. “I just watch the kids run around and have fun and laugh. Logan would have loved that. I used to have to drag him out of here.”

That thought is enough to draw a smile out of Kelly.

“Sometimes I would wonder, will they remember him?” Kelly said. “Time goes on. People move on.”

Kelly paused, then looked around the arena again.

“You know he will be,” he said. “This will be here forever.”