Sep 22, 2016

NHL rapidly moving toward international game

The gap in sheer physicality observed at the international level against that observed in the NHL is shrinking, Travis Yost writes

By Travis Yost

The World Cup of Hockey’s pool play wraps up Thursday, and generally speaking, it has been a success.

One of the big drivers of this success has been Team North America – a roving band of young Canadian and American players who compete at a blistering, hyper-aggressive pace. Their style of play has earned plaudits from all corners of the sport – mostly, I presume, because it’s the type of entertaining product that all fans can embrace.

Another, perhaps less noticeable element of the World Cup of Hockey: the rough stuff just hasn’t been there. This is a trend we tend to see in international hockey because of restrictive rules with major penalties, including fighting. Teams of varying competencies have simply gone out and played skill against skill. For the most part, fans have embraced it.

In years past, the difference in sheer physicality observed at the international level against that observed in the National Hockey League would seem night and day. The NHL has earned a reputation – right or wrong – of harbouring this sort of style of play.

But, I couldn’t help but notice that for the first time in a long time, the disparities between the two didn’t feel off by orders of magnitude.

Why? Well, through a combination of policy changes and the evolution of the sport, the rough stuff has taken quite the backseat.

The primary driver here seems fairly obvious: The league’s clampdown (one that will aggressively evolve due to both internal and external pressures) on fighting has played a major role. Recognition of the dangers – and, perhaps, a recognition of the lack of any value-added elements – of fighting has had a substantial chilling effect on its frequency. Enforcer types have essentially been rendered extinct, and it’s made fighting across regular skaters quite rare.

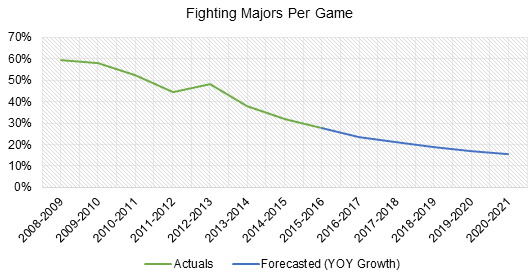

How big of a drop-off has the league realized? Below is a look at the historical fighting majors per-game since the 2008-09 season. I’ve forecasted out the next five seasons based on average year-over-year changes. As you can see, if the league continues degrading at this pace, fighting will become relatively infrequent within the next five years.

It’s almost unfathomable to think that less than a decade ago the NHL was a league in which approximately 60 per cent of games had at least one fight. Today that number is under 30 per cent.

If the league continues moving in this direction – and based on what we know, there’s no reason to assume it will reverse course – we should see that number hit approximately 15 per cent by the 2020-21 season.

Fighting is the obvious starting point when trying to illustrate the type of development the league is working through right now. But it’s important to note that this type of change isn’t strictly limited to fighting.

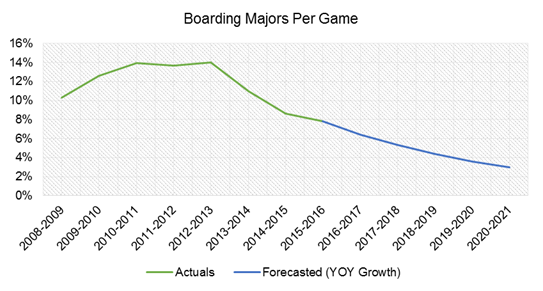

By way of example, let’s look at boarding majors. Boarding penalties are some of the most dangerous and violent types of infractions the league has to offer, and unlike fighting, these frequently happen (a) in the run of play; and (b) are often unilaterally effected. This is important because, unlike something like fighting (or more specifically, staged fighting), a change in frequency would really have to be driven primarily by players changing the way they treat these types of encounters.

So, how do boarding penalties look?

What’s interesting here is that unlike fighting, the change in behaviour here is something that’s been experienced rapidly over the last few years (instead of at a consistent rate since, say, the 2008-09 season). In the last three years, boarding penalties have been greatly reduced year-over-year to the point where we are only seeing them in about 8 per cent of games played. Much like fighting majors, if we believe the behavioural patterns will remain in future periods, we should eventually see that number hit a lowly 4 per cent for a full season.

All this to say that the NHL, very quietly and yet very rapidly, is moving extremely close to the international game. If you listen to Gary Bettman, Bill Daly and the NHLPA, they will emphasize that elements like fighting and grey-area play are going to stay as a part of the game until the end of the time. Maybe they are right. But what they are masking, overtly or implicitly, is the fact that the sport has really cleaned itself up over the last decade.