May 19, 2020

The evolving role of the modern power-play defenceman

Shots from the blueline are getting harder to find as more teams run their power play through playmakers on the wings, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

Last week, I spent some time looking at the power-play shot profiles for Alexander Ovechkin and Auston Matthews. One of the principal conclusions was that as players understand how best to optimize their offensive skill sets and those of their teammates, teams begin to develop their own identity.

In other words: power play setups tend to be as productive as the talent involved.

Looking at the Washington Capitals on the power play over the years, it’s interesting to note how they’ve utilized their personnel, particularly with respect to defencemen. Washington’s used a four-forward setup for a few seasons now, with the defenceman role shared between the likes of John Carlson and Dmitry Orlov.

Carlson in particular has a fantastic shot and can act as a valuable relief valve, but the juice from this power play really comes from the forwards – a group that includes offensive talents like Ovechkin, T.J. Oshie, Evgeny Kuznetsov and Nicklas Backstrom.

One thing that has always been noticeable within the Washington power play is that the defencemen shoot sparingly. This season, forwards in Washington accounted for 83 per cent of shot volume on the power play, the highest number in the league. (The league’s best power play, in Edmonton, was at 82 per cent.) By design, these power plays intend to funnel the puck through the playmakers on the wings and towards shooters in the slot or the circles. Shots from the blueline? Those are hard to find.

It’s not a trivial data point. A few years ago, teams started to shift towards a four-forward power play because it yielded more scoring opportunities and, consequently, goals. We have started to see another shift, too – teams running power plays through the forwards more than defenders walking the blueline.

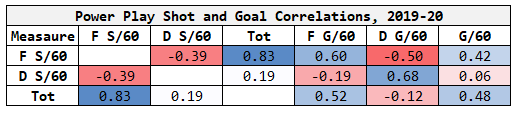

If we look at the 2019-20 season, we can look at what relationships between shots and goals mean for forwards, defencemen, and power play productivity more broadly (here, a correlation of 1.0 indicates perfect positive correlation):

What we find is that teams who saw forwards taking a higher proportion of available shots observed two changes: defenders shooting and scoring less, but the overall five-man units scoring more. Conversely, teams where defenders took a higher proportion of available shots saw forwards scoring less, and power-play units scoring less as a result.

It’s not a one-size-fits-all scenario, and is certainly contingent on the talent available for each team.

The St. Louis Blues – who feature plenty of defencemen on their power-play units including Alex Pietrangelo, Vince Dunn, Justin Faulk, and Colton Parayko – finished third in the league in rate scoring.

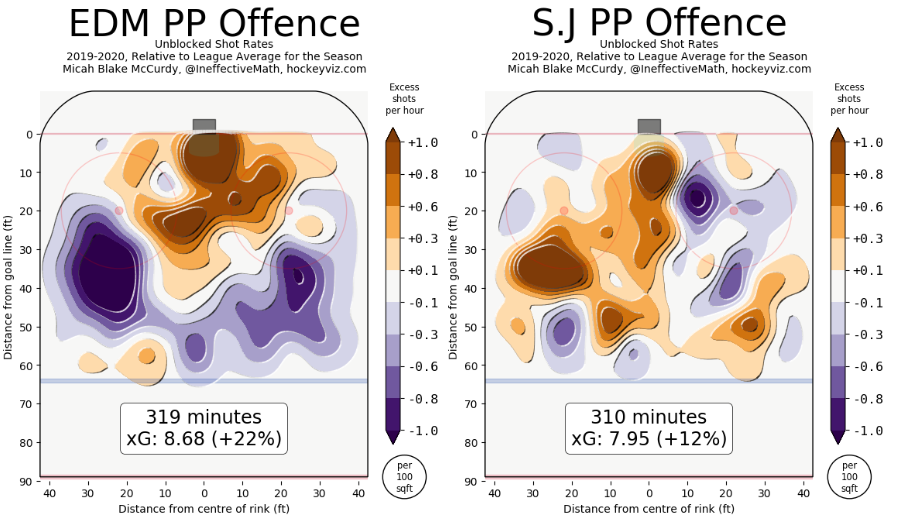

But let’s consider two teams at opposite ends of the spectrum. I mentioned Edmonton earlier – league’s best power-play unit, with the second highest percentage of shots coming from forwards. On the other hand let’s look at San Jose, a team featuring two of the most prolific blueline scorers we have seen in Brent Burns and Erik Karlsson. I put each team’s power-play shot maps side by side, courtesy HockeyViz:

The Oilers' power play may be predictable: there aren’t many threatening options from the blueline, but Connor McDavid and Leon Draisaitl were the most lethal scoring duo in the league. As a result, the Oilers worked aggressively at finding shooting areas in the low and mid-slot – areas of the ice where shooting percentages tend to skyrocket. It’s surely harder to pierce the interior of opposing defences as opposed to taking shots from the perimeter or the point, but the reward is also substantial.

On the other hand, the Sharks – a team that’s seen most of its dynamic forwards age off of the roster and feature two electric offensive defencemen – tend to run a lot more of their offence from the blueline. But Karlsson and Burns aren’t just distributors. Plenty of shots tend to manifest from the point, where volume is easier to achieve, and quality harder. And whereas the Oilers shot a blistering 20 per cent on the power play over the course of the season, the Sharks shot just over 10 per cent – good for 31st in the NHL.

It’s not as simple as “take all of your shots from as close as possible” – if it was, the jobs of coaches and players alike would be easy. You need the talent to run the systems you intend to implement.

But if the evolution of the power play has taught us anything, it’s that defencemen have been marginalized both in how much they are deployed and how much of the offence they’re responsible for generating.

Data via Evolving Hockey, HockeyViz, NHL.com