Jun 20, 2016

Johnson saves US Open from embarrassing ending

Dustin Johnson's multi-shot victory at the US Open Sunday saved the USGA from what could have been an embarrassing situation after their incomprehensible review on a ruling earlier in the round, TSN's Bob Weeks writes.

By Bob Weeks

Let’s pretend for a moment we’re at Game 7 of the Stanley Cup final. There’s four minutes left, and one team scores to tie the game 4-4. But before the puck drops to resume play, the referee comes over to the bench and tells the coach, “It looks as if there may have been a high-sticking penalty on that last goal. We’re going to review it at the end of the game and let you know if that’s a goal or not.”

You can imagine the outcry that would ensue.

While that scenario seems unfathomable, almost ridiculous, it’s what happened on Sunday at the U.S Open. The United States Golf Association decided to rule on a ruling that was already made, but they wouldn’t make that ruling on the ruling until after play concluded.

Got that?

The unthinkable scenario began when Johnson was going to putt on the fifth hole. He put his putter down beside the ball, two practice swings, and moved his putter behind the ball, hovering it over the ground. The ball rolled back towards his putter a fraction of an inch and Johnson immediately backed away.

He called in a rules official, who assessed the situation and asked Johnson if he’d caused the ball to move. He said no. So, too, did Lee Westwood, his playing partner. The official asked once more and got the same answers and deemed there to be no infraction. End of story.

Or so we thought.

In an incomprehensible move, when Johnson got to the 12th tee, Jeff Hall, the USGA's managing director of rules and competitions, met him there and informed him they were reviewing the video of the situation and might assess him a penalty stroke after the round.

That’s right, after the round.

At that point, they might as well have turned off the scoreboards and put blindfolds on all the golfers.

Not only was the USGA throwing its own walking official under the bus, they were telling Johnson and Westwood they didn’t believe them. Trust? Out the window. Respect for the players? None. Belief in their own officials? Nope.

From that point on, the focus of the broadcast became the USGA’s handling of the situation. The shots being hit by the best players on a fiery golf course were a secondary story. The USGA became the star of the show.

Thankfully, Dustin Johnson saved their bacon from complete embarrassment with a multi-shot victory. Of course, by the time he rolled in his final putt, the USGA had already been deep fried on Twitter. Not only were golf fans tearing them apart, but so, too were Johnson’s peers.

Tiger Woods called it a “farce” and Jack Nicklaus said the decision was “terrible” and “very unfair.”

Rory McIlroy and Jordan Spieth served up harsher criticisms.

How the USGA could think putting Johnson’s scorecard in limbo as he played the back nine was protecting the game is beyond the comprehension of most. How it could not see the deluge of criticism this move would create is also stunning.

Trying to defend the move, Mike Davis, the USGA’s executive director, told Alan Shipnuck of Sports Illustrated, "People are going to be upset however we rule. Bottom line, we have to follow the rules no matter what."

The trouble is, the rules are so subjective they can be followed in almost any direction. Golf is supposed to be a game of honour and respect, where players call infractions on themselves. The final decision should really reside with the player.

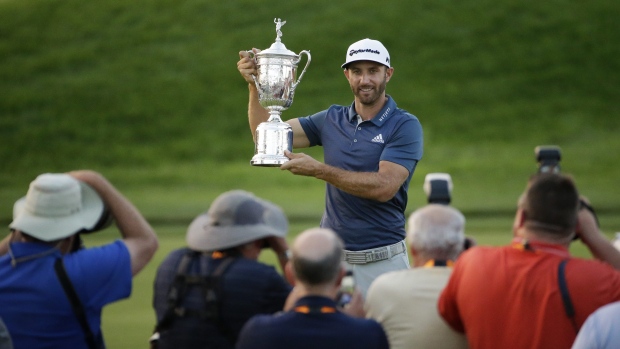

“I still know I didn’t cause the ball to move,” Johnson told me not long after he accepted the trophy for his first major. “I know the rules. If I would have caused the ball to move, it’s a penalty and you just go on. It happens some times.”

Johnson accepted the penalty, not really caring much at that point, raising his final-round score from 68 to 69. But just because this issue didn’t affect the outcome of the tournament this time doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be rectified so it doesn’t happen again.

But while he walked away as a champion, the USGA left Oakmont with egg on its face. What should have been a wonderful championship is instead another example of how golf continually shoots itself in the foot.