Nov 11, 2016

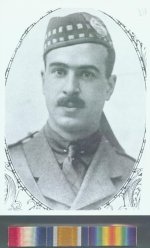

Geoffrey Taylor: Olympic rower fought at Passchendaele

TSN’s Bob Weeks traveled to Belgium to visit the battlefields and cemeteries of the First World War to profile some of Canada’s top athletes of the day who made the ultimate sacrifice more than a century ago.

By Bob Weeks

In early May of 1915, William and Stella Taylor, the parents of Geoffrey Taylor of Toronto, received a telegram that undoubtedly haunted them for the rest of their lives.

“Sincerely regret to inform you that Lieut. Geoffrey Barron Taylor, 15th Battalion, is reported missing. Further particulars when received will be sent [to] you.”

There were no further particulars. Like so many soldiers in the First World War, and specifically those who fought at Passchendaele, Taylor’s body was never found. A week earlier, he’d sent a letter home to his parents and now, at the tender age of 25, he was simply gone forever.

In his short life, Taylor accomplished a lot, especially in sports. A standout student and athlete at the University of Toronto, he played football for the school, noted as an exceptional lineman. He was also said to be a standout on the rugby team.

However, it was as a rower that Taylor had his greatest athletic achievements. A member of the Toronto Argonaut Rowing Club, Taylor, as part of a coxless four, won numerous Canadian championships. To this day, his achievements stand out for a club that has produced numerous champions.

In 1908, he was part of the Canadian team that headed to London for the Summer Olympics. He was a member of the bonze-medal winning boat in the coxless four and then joined the men’s eight that won another bronze medal. He went back to the Olympics in 1912 but failed to finish inside the top three.

At the outbreak of the war, Taylor was studying at Trinity College, at Oxford, having won a scholarship while at the University of Toronto. But he put his studies aside, enlisted and was commissioned into the 15th Battalion as a lieutenant.

He and his comrades were in the front lines near St. Julien, Belgium, on the morning of April 24 when the Germans opened the taps on some 5,000 tanks of chlorine gas, which then drifted towards the Canadians, inflicting horrendous losses.

A Canadian soldier who was there, Private Tom B. Drummond, later described the horror:

“Quick peeks over the edge of our shell holes discovered a line of men on our left leaving the line, casting away equipment, rifles and clothing as they ran. Some managed to get halfway to where they were going only to fall writhing on the ground, clutching at their throats, tearing open their shirts in their last struggle for air, and after a while ceasing to struggle and lying still while a greenish foam formed on their mouths and lips.”

The battalion suffered 675 casualties on that one day, the largest loss for a Canadian battalion in the entire war.

Taylor was last seen heading to an abandoned farmhouse just behind the front line and it’s presumed he died from gas poisoning but his body was never found.

Today, a moving monument marks the spot where the Canadians faced the gas attack. Known as the Brooding Soldier, it is a haunting statue on what is now a peaceful intersection renamed Vancouver Corner.

Taylor was far from the only soldier whose body was never found. Tens of thousands of soldiers never received a proper burial, their bodies having simply disappeared without a trace.

To honour them at the end of the war, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission built the Menin Gate in Ypres. On the inside of it and on its ramparts are the names of 54,395 soldiers, including 8,000 Canadians. It is here where Taylor’s name can be found.

As a show of respect for these men, every night at 8 p.m., the road underneath the Menin Gate is closed and a ceremony is held with the playing of the Last Post. It has been done this way every night, rain or shine, warm or cold, since July 2, 1929, with the exception of when Germany occupied Belgium in the Second World War.

It seems a fitting tribute for Taylor, a Canadian athlete and Olympian who made the ultimate sacrifice.