Jan 27, 2017

Red Wings need a change of direction

With Detroit’s historic playoff streak in jeopardy, the time has come to ditch some contracts and build around the kids, Travis Yost writes

By Travis Yost

It feels weird to type these words, but the Detroit Red Wings are a struggling hockey team.

Let’s be clear – it’s so jarring because the Red Wings have been a staple of excellence for so long, racking up 25 consecutive playoff appearances with a few Stanley Cups sprinkled in. All we have ever known is that, regardless of divisional/conference alignment, the Red Wings would surely hold down one of the 16 playoff spots.

But, for the first time in a long time, that’s in jeopardy. Heading into Thursday, the Red Wings were playing at an 82-point pace – which seems average until you remember that said 82-point pace would be good for dead last in the Eastern Conference. The defence-optional New York Islanders, rebuilding Buffalo Sabres and everything-has-gone-wrong Florida Panthers are all currently situated ahead of general manager Ken Holland’s team.

What’s really interesting about the Red Wings’ decline is that it hasn’t been a sharp, unexpected nosedive off a cliff. They had a few years of build-up to elite hockey performance, a few years where they were legitimate contenders, a few years where making the postseason seemed like a chore, and now this – whatever this is.

This kind of slow regression in performance can be undetectable when your main measure is whether or not a team makes the playoffs, but it’s real.

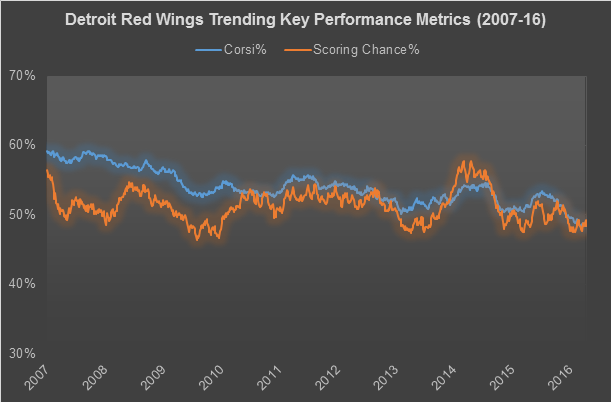

Consider their trend of goal and shot differential over the last 10 years as a way of one quick example. You can see all of those eras captured. You can also see how disparate this season’s version is from the successful teams of the past:

Over basically any 50-game block in the last decade, the Red Wings were always out-shooting and out-chancing their competition. That’s historically proven to be the best recipe against percentage volatility – if you are simply getting more chances to score, you’re going to win on the goal differential front over the long term. The Red Wings have done that for a long time.

This year, though, that’s changed. This is really the first consistent run the Red Wings have had under 50 per cent on both shots and scoring chances in the modern era (though they did have one brief downturn in 2009-10, the year where they were leapfrogged by new powerhouse Chicago in their own division).

I think this is the sort of degradation you would expect from an aging, capped-out lineup that was built to win a Stanley Cup five years ago. There’s probably a great discussion to be had as to whether or not Holland – the active GM during this entire run – pulled the trigger on the right moves as he waded through varying levels of competency. At some point the Red Wings’ quest for a Stanley Cup died, and it was assuredly well before Holland started managing for the future.

Here’s the biggest problem if you are a Red Wings fan: Holland of 2017 can’t easily recover from Holland of years past.

The current NHL landscape on a contract level is pretty straightforward: you need your highly paid veteran players to come close to out-performing their contracts, and you definitely need your young players to develop and pay off on their first and second contracts.

Detroit has issues on both fronts, but the former is really notable if you have an eye toward the future. (It’s worth noting that they did lose a Hall-of-Fame talent to the KHL for nothing – even if Pavel Datsyuk was past his prime, replacing that calibre a player is tough.)

The big contracts shake out as follows.

Henrik Zetterberg: A $6.1 million cap hit through 2021. Zetterberg has been reasonably productive this year, but he’s producing at a second-line player rate at this point (despite first-line pay). That’s doable for now, but how is Detroit going to reconcile his contract and fading performance over the next four years? The sheer financial liability of his contract makes him tough to move, even if Detroit wanted to.

Frans Nielsen: A $5.25 million cap hit through 2022. Nielsen ranks 241st out of 348 qualified forwards in rate scoring this year (1.4 points per-60 minutes at 5-on-5) and on the ice for 48 per cent of the goals (seventh best among forwards in Detroit). Combine his average scoring with quality defensive play, and you have perfectly acceptable performance for a middle-six forward. The problem, of course, is that this was supposed to be Nielsen’s best year – he’s already 32, and signed for another five seasons. I sense his contract is absolutely moveable, but the timing on that is probably sooner rather than later, if that were a route Detroit realistically considered.

Gustav Nyquist: A $4.75 million cap hit for three more years. He’s in his prime, and he’s fantastic. This is a core piece now and tomorrow for Detroit.

Justin Abdelkader: A $4.25 million cap hit through 2021. This contract is unmovable and, quite frankly, ridiculous. He’s been out-scored over multiple years by the likes of Andrew Shaw, Sam Gagner, Ryan Garbutt, Antoine Roussel, and Jamie McGinn – all players who are making millions less in both cap hit per year and the total liability of their contract.

Darren Helm: A $3.85 million cap hit through 2021. This deal is indefensible for many of the same reasons noted with Abdelkader. Helm can do some nice things for your team, especially on the penalty kill. But is this type of grinder really worth so much financial liability long term?

It’s much the same story on the defensive side. The team has $15 million in cap hits across three players over the age of 30 in Mike Green, Niklas Kronwall, and Jonathan Ericsson. Green has looked reliable this season, Kronwall and Ericsson less so.

Most of these contracts become at least pseudo-defensible if you’re a team with legitimate Stanley Cup aspirations. If you are a team that’s sitting dead last in the conference and appear years away from contending, I think you have to wonder whether the money committed long-term to some of these names (except Nyquist) makes sense.

The good news if you are Detroit? Well, there’s Nyquist, mentioned above. Tomas Jurco, Dylan Larkin, Anthony Mantha and Andreas Athanasiou are good young players. And you have goaltending. If I’m Holland, I’m trying to figure out how to ditch some of those contracts to turn attention toward building the next wave of a contender around these names.

Because the current plan just isn’t working out.