Oct 27, 2016

Here's why Canucks fans should be concerned

The Vancouver Canucks' cycle game in the offensive zone has turned to dust, Travis Yost writes, limiting the team to far too many one-and-done opportunities.

By Travis Yost

Despite a respectable start to the season in the win/loss column, there are plenty of reasons to be concerned if you are Vancouver Canucks head coach Willie Desjardins.

The Canucks have opened the season with a 4-2-1 record, primarily driven by some fantastic goaltending from Ryan Miller and Jakob Markstrom. That counts for something – teams with above-average shot-stopping ability can mask deficiencies, sometimes for extended periods of time.

But, as the story always seems to go, the modern era of hockey is cruel to this type of team. When hot goaltending cools, the team will be left to reconcile its brutal shot differentials. The Canucks, as it stands through Wednesday, are the league’s worst team at possessing the puck at 5-on-5, controlling just 43.6 per cent of play. That’s the type of performance that puts a team into the draft lottery far more often than not.

It’s an interesting evolution for a Canucks team that just a few years ago was the cream of the crop at owning the run of play, attacking with incredible fluidity and creativity.

The offence is really where the team has taken a turn for the worse. The Sedins still have their occasional flash of brilliance, but nothing like what we saw during their peak years. Behind the Sedins the team offers little to nothing in terms of dangerous attack, and their cycle game – which used to be a staple – has turned to dust.

Their cycle game (or controlled attack game) degradation is quite real, and probably one of the biggest reasons why the Vancouver attack has disintegrated over time. Watch a Canucks game this season and notice just how frequently the team is limited to one-and-done opportunities.

There’s an easy way to measure this: Multi-shot shifts (MSS), or instances in which a team generates a second shot-attempt immediately after generating an initial shot-attempt. We can calculate these numbers by using the NHL play-by-play sheets and getting creative with the logic, using intervening events (like faceoffs, for just one example) as exclusionary criteria. We’ll also set a timeframe for what we consider a multi-shot shift in order to ensure that the puck was unlikely to have exited and re-entered the offensive zone. In this exercise we’ll say the second shot had to have happened 10 seconds or less after the first shot.

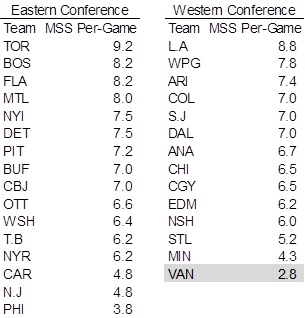

Where does Vancouver rank? Dead last, and more than two standard deviations away from the league average in 2016-17.

The numbers you are looking at are per game, so how it reads is pretty straightforward: about 2.8 times per-game at 5-on-5, Vancouver will sustain their attack in the offensive zone by sending multiple shots at the direction of the goaltender. The league average here is about 6.5 per-game, and you can see a number of teams – including Toronto, Boston, and Los Angeles – are sustaining their attack about 8.0 times per-game.

As an aside, I’m really intrigued by both Arizona and Colorado’s position here. The teams at the top of the list generally align with the teams who are better at controlling possession to start the year – all of the Leafs, Islanders, and Kings are above the break-even line in Corsi%, and they’re probably doing so by (a) beating opposition into their defensive zone; and (b) keeping them there.

The Coyotes and Avalanche, though, are basically neck-and-neck with the Canucks on the opposite end of the Corsi% spectrum. It seems to me that this could be the case of teams that either counterattack extremely well, or recover pucks in the offensive zone (in the off-chance they’re actually there) extremely well.

Let’s get back to the Canucks’ situation. The next question you’d be inclined to ask with such a lowly number concerns who is (and who is not) on the ice for Vancouver in the event they actually do sustain an attack. You won’t be surprised that the Sedins have been on the ice for about half of the team’s total multi-shot shifts. (The Hutton-Gudbranson pairing has also been on the ice for a good chunk of these events.)

I think this is a starting point for troubleshooting what’s currently chipping away at this team’s effectiveness. When teams can’t sustain attacks, they’re left to defend far too frequently. The more you defend, the more mistakes your team can make and the more your goaltender is forced to bail you out. It’s a trickle-down effect, one that the Canucks would be wise to work on in the coming months.