Jul 6, 2021

Bischoff looks back on the New World Order 25 years later

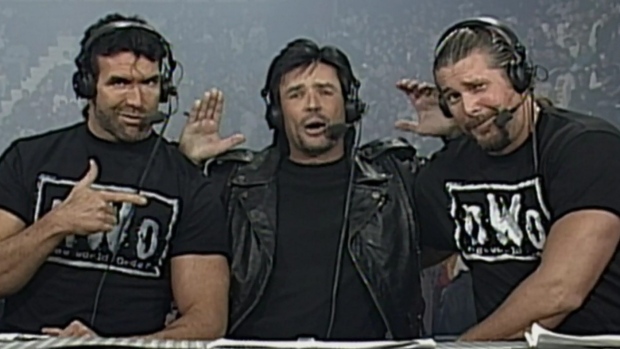

It was on July 7, 1996 that Hulk Hogan made his infamous heel turn and the New World Order was born at World Championship Wrestling's Bash at the Beach. Twenty five years later, TSN.ca caught up with the man behind the NWO, Eric Bischoff, to look back at one of the most transformative events in pro wrestling history.

, TSN.ca Staff

July 7, 1996. It’s a day that will forever live in infamy in the world of professional wrestling and one that helped herald in a boom period in the industry, the likes of which many organizations have been trying in vain to replicate for much of the past two and a half decades. The night of July 7, 1996 was when the New World Order was born.

In the main event of World Championship Wrestling’s Bash at the Beach pay-per-view, the WCW all-star team of Sting, “Macho Man” Randy Savage and Lex Luger would take on the team of Scott Hall, Kevin Nash and a mystery partner. Hall, who previously spent time in WCW under his real name and then as “The Diamond Studd,” was well known to fans as former World Wrestling Federation star Razor Ramon. He showed up in the front row of a WCW Monday Nitro show in late May, promising a “hostile takeover” of WCW. A few short weeks later, he would be joined by Nash, another former WCW performer who went on to stardom in the WWF as Diesel. They promised the arrival of a third member of their group who would be revealed at the PPV as they would take on the best WCW had to offer. For weeks, there was a buzz among fans and throughout the industry about who this third man might be.

When the match began on that Sunday night in Daytona Beach, FL, there was no sign of a third man. Hall and Nash worked the match a man down against Sting, Savage and Luger. But in the latter stages of the bout, there would be an arrival that nobody expected. With Hall and Nash in control, Sting and Luger on the outside, and Savage down in the ring, Hulk Hogan made his way down the aisle and headed ringside much to the delight of the crowd. Hall and Nash bailed from the ring, leaving Hogan alone with the prone Savage. As Hogan soaked in the jubilation from a crowd that hadn’t seen him in months, he did the unthinkable – Hogan hit Savage with his trademark Atomic Leg Drop and then hit it a second time.

It was Hogan. Hogan was the third man in a heel turn that few thought they would ever see. Hogan threw referee Randy Anderson out of the ring as the trio continued their assault on Savage. Garbage began to rain down on Hogan, Hall and Nash in the ring from a crowd that was both irate and incredulous. Broadcaster “Mean” Gene Okerlund came down to get a word from the three men and it was then that Hogan introduced the world to the “New World Order of wrestling,” turning his back on the fans and declaring war on WCW.

The introduction of the NWO (stylized as “nWo”) was a bonanza for WCW. This battle between the ever-expanding NWO and WCW was a ratings smash with Nitro topping the WWF’s Monday Night RAW in the “Monday Night Wars” ratings battles for 83 consecutive weeks. The black-and-white NWO T-shirt became ubiquitous at wrestling events and just about everywhere else in the late ‘90s with merchandise sales skyrocketing for WCW. Celebrities like Jay Leno, Dennis Rodman and Karl Malone would eventually get involved in NWO-related angles.

For Eric Bischoff, the man behind the NWO angle, the introduction of the New World Order was a transformative event for professional wrestling like few before it and few after.

“I think the NWO, in the storyline, in the presentation of the NWO, presentation of the characters in the NWO really changed the industry probably more than anything since Vince McMahon went from being a regional territory under his father to becoming a worldwide territory and really changed wrestling back in the ‘80s,” Bischoff told TSN.ca. “But I think other than Vince McMahon really going national and international with the WWE product, I don’t think anything has had more of an impact on the profession wrestling industry than the NWO and all of the things that came with it.”

A native of Detroit, Bischoff got his start in professional wrestling in the late ‘80s working in sales for Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Alliance before becoming on-air talent in 1989. Joining WCW as an announcer in 1991, Bischoff entered the executive ranks in 1993 and by 1996 was the company’s senior executive vice-president. With the NWO angle, Bischoff was thinking big and outside the box.

While the long-held belief is that Bischoff got the idea for the NWO from New Japan Pro-Wrestling’s inter-promotional rivalry with the Union of Wrestling Forces International (UWFi), he insists that isn’t the case.

“To this day, I’ve never spent 10 seconds watching any of that,” Bischoff said. “I was completely unaware of it. It is a narrative that, I think, was created by a bunch of cosplay wrestling journalists, who tried to frame the NWO in that story in a way that suggested it was a derivative of something else and it was not original. And nothing could be further from the truth. The fact of the matter is that I had been spending quite a bit of time in Japan in ’93, ’94, ’95, simply because I was doing a lot of work throughout the year with New Japan Pro-Wrestling and on those occasions when I would go to Japan, I’d pay close attention to the overall presentation – the overall, not a specific storyline – because when I would go to Japan, I would go to Japan for two or three days at a time for a special event and I would always see a New Japan event. I wasn’t there watching UWFi or All Japan Pro Wrestling or anything else.”

Bischoff says the inspiration he took from Japanese wrestling was strictly in terms of a change in presentation. While North American wrestling – namely, the WWF and WCW – was still largely about exaggerated characters, NJPW had shifted its focus to a more reality-based product. Bischoff thought North America was ready for the same.

“It was less cartoonish,” Bischoff said of the New Japan product that caught his eye. “It was more formal like other sports. It had a very much of a big boxing feel to it. Not only in the way the matches were presented, but in the way that the events were promoted and the way they were publicized and the way the Japanese media and local media presented the product and that was a stark contrast to what was going on in the United States back in ’93, ’94 and ’95, where WWE, predominantly, and WCW were presenting the product as more of a teen and preteen product, meaning the characters, the storylines and the presentation as a whole was much more cartoonish.

“So the distinction that I came away with was – by the way, in the United States and North America at that time, professional wrestling was suffering. If you went back and looked at where WWE was in ’93, ’94 and ’95, their house show attendance was down and it was deteriorating dramatically. Their television ratings were flat, at best, whereas in Japan with a more realistic version of wrestling, and because of the way it was promoted and marketed and covered in the media, it was a more of an 18-to-49-year-old product or presentation.”

Hall and Nash’s availability to get the angle rolling was a happy accident for Bischoff.

“I didn’t even know that Scott Hall and Kevin Nash were thinking about leaving WWF,” Bischoff said. “I had no contact with them. I wasn’t reaching out to them to get an idea of where they were at contractually. For all I knew at that time, in ’96, was that they were under long-term contracts. It wasn’t until Scott Hall initially reached out to me and actually, he didn’t even reach out to me, he reached out through a mutual friend, Diamond Dallas Page (DDP), and Scott Hall’s inquiry was something to the effect and I’m paraphrasing here, ‘Hey, I’m thinking about leaving. Do you think there’s a spot for me? Could you talk to Eric Bischoff for me?’ And Diamond Dallas Page came to me and said, ‘Hey, Scott Hall is available and there’s a chance Kevin Nash may be, as well,” which is something that DDP picked up from Scott in their conversation and I said, ‘Sure, I’m happy to talk to them.’ Subsequently, I had a couple of conversations with Scott and his agent at the time and then almost immediately thereafter, I had a conversation with Kevin Nash, who also reached out to me.”

Bischoff realized quite quickly that this duo was perfect for what he wanted to do with what would become the NWO.

“It’s about that time that it occurred to me that, wait a minute, I’m looking for a reality-based storyline,” Bischoff said. “I’m looking for something that’s completely different than what the American or North American audiences were used to seeing. Here I’ve got two guys who were formerly in WCW, didn’t really like the way they were being treated, didn’t think they were getting the opportunities that they wanted. They went to WWF, they had a fair amount of success in WWF and now they wanted to come back to WCW. That set up my storyline. That was the foundation for it. Now clearly, Scott Hall and Kevin Nash had both become very big stars in WWE. Their ‘Q factor,’ as we refer to it in television, was much higher than it was when they left WCW, so certainly, them coming over, particularly coming over from WWF, set up that invasion-type premise that was at the core of the NWO.”

As for the third man to complete this initial incarnation of the NWO, well, it wasn’t going to be Hogan. Bischoff didn’t plan on even pitching the idea to him because he figured it would be a nonstarter.

“I had a conversation with Hulk about eight months prior to Scott Hall and Kevin Nash coming in, where I suggested to Hulk that, perhaps, he might consider turning heel and doing a 100 per-cent overhaul of the character,” Bischoff said. “That was eight months prior, like I said, to Scott Hall even reaching out to me or the idea of the NWO even beginning to form in my head and I was summarily escorted out of his home. He did it very elegantly, I might add. He wasn’t mean or aggressive about it, but nonetheless, he made it clear to me that he had no interest in turning heel.”

Hogan would, of course, have second thoughts. On hiatus from the company and filming a movie, Bischoff says the man who would soon become “Hollywood” Hulk Hogan was intrigued by what he saw on WCW TV.

“He was on location doing a movie he couldn’t leave, so he asked me to fly out and have a conversation with him – a creative conversation,” Bischoff said of Hogan. “So I flew out to LA and we sat down and by this time, Scott Hall had already made his first appearance and Kevin Nash had made his subsequent appearance, and the story was beginning to unfold on television and Hulk was very much aware of that. So, like I said, he called me; I flew out to LA and I met him after he was done shooting and we went into his trailer and he said, ‘So, Eric, who’s the third man?’ and frankly, I didn’t want to tell him because I was working very hard to keep that third man a secret from as many people as I could and only a small handful of people knew - very small – like you could count it on one hand and have two fingers left over. So I said, ‘Well, Hulk, who do you think it should be?’ and he said, ‘You’re looking at him, brother.’ So I said, “Oh, okay. So you’re ready to turn heel?’ and he said ‘Absolutely.’ So that’s when it became Hulk Hogan.”

But since Bischoff didn’t originally consider Hogan for the role as the NWO’s mystery member, it had already been promised to somebody else – somebody who Bischoff would now have to tell he’d been passed over.

“Now prior to that meeting with Hulk, really only a couple of months before the pay-per-view, maybe a month and a half, it was going to be Sting,” Bischoff explained. “I had numerous conversations with Sting and convinced him – and it wasn’t too hard – that Sting going from the very colourful surfer, glittery kind of ‘Wrestler on Ice’ character and turning heel would be good for his career. It would be good for WCW and make a fascinating story and Sting agreed. So after Sting had agreed and then subsequently I got a phone call from Hulk Hogan, I was faced with a kind of a dilemma. I’ve already talked one of our biggest stars in Sting into turning heel, but now I’ve got Hulk Hogan, who arguably was a bigger star, wanting to play that same character. So I had to sit down with Sting and have that conversation, which I did, and he was extremely professional about it and he was highly supportive of it and that’s when we made the move from Sting to Hulk Hogan.”

In order to properly pull off Hogan’s surprise return and shocking heel turn, not even the announcers for Bash at the Beach – the team of lead announcer Tony Schiavone and colour commentators Dusty Rhodes and Bobby “The Brain” Heenan – were told ahead of time what was to come. The broadcasters were set to learn of Hogan’s perfidy in real time because Bischoff wanted a real and natural reaction to it. He got just that, but perhaps to a detriment.

As Hogan made his way down the aisle, Heenan, a heel whose character had hated babyface Hogan for years and thought him to be a phony, asked “Whose side is he on?” He had inadvertently tipped off Hogan’s turn. But Heenan’s skepticism was perfectly in line with his deep-seated disdain for the Hulkster.

“Saying what Bobby did, truthfully, he should have known better because even if he felt that and knew that and believed that, he was also enough of a professional to know that that’s the kind of comment you’d want to keep to yourself until after you see it,” Bischoff said. “It would have been fine afterwards for Bobby to go, ‘I’ve been telling you people for years! You should have listened to me!’ That would have been perfectly fine, but to tip his hand was not professional. Now, I understand it, too, because I got exactly what I wanted; a natural reaction, but it would have been preferable had he not done it.”

As the NWO angle began to dominate WCW programming in the weeks and months following Bash at the Beach with the faction growing in number of prominence, a funny thing happened when it came to fan reaction. Quite clearly despised heels at the outset of the angle, the NWO started to get cheered – first a little, but then a lot.

“When Hulk Hogan turned, and the NWO became a thing, for the first couple of months, most talent were so taken aback by it because Hulk Hogan got, obviously, one of the strongest heel reactions anybody in the United States or Canada had ever seen,” Bischoff said. “Most of them, unless you watched Mexican wrestling, had never seen that kind of reaction ever in their lives. However, after the initial turn of Hulk Hogan, if you go back and watch some of the Nitros or pay-per-views for the next couple of months, the heels were getting cheered for the most part. Now, you still had a very loyal, kind of traditional WCW audience who felt that the NWO was stomping a mudhole in their favourite promotion and their favourite wrestlers. You did have a little bit – I would say 25 per cent, perhaps – of the audience react negatively to the NWO, but at least 50 to 75 per cent were cheering them on. That was a new phenomenon. The babyface is getting booed and the heel is getting cheered? What the hell?”

As the NWO rose to prominence in WCW, “Stone Cold” Steve Austin was taking the WWF by storm. North America’s two largest promotions’ most popular acts and biggest merchandise-movers were ostensibly traditional heels being embraced by the fans. Bischoff says it was just a product of changing tastes.

“I think the NWO storyline tapped into a prevailing undercurrent in pop culture for the anti–hero,” Bischoff said. “It wasn’t just in wrestling. Wrestling caught on late. The NWO was late to the anti-hero dance. But if you watched characters in movies at that time, your central characters, the most popular characters in any film were anti-heroes. They were flawed badasses and people love flawed badasses. They still do to this day as opposed to a milk-and-cookie, or as Hulk Hogan used to say, ‘Take your vitamins and say your prayers’ babyface. That kind of babyface was long gone in American pop culture taste, whereas the NWO were badasses who didn’t give a f--- and people loved that. They still do to this day. So I think in wrestling at least, the NWO was the first storyline characterization of performers who kind of embraced that anarchy, anti-hero persona and the audience reacted accordingly.”

By that fall, Bischoff would get in on the act himself. On a November edition of Nitro, it was revealed that Bischoff had been in league with the NWO all along and was the mastermind of their invasion. Leaving his broadcasting duties, Bischoff became a full-time manager and spokesperson for the group and one of the most hated heels in the industry.

Bischoff believes that his unmasking as a confederate made perfect sense for the storyline, so it didn’t take a lot of convincing to become part of the angle.

“The reason it didn’t take a lot of thought or conversation was because the story wrote itself,” Bischoff said. “The NWO, as an organization or faction, was coming in to take over WCW. The Bash at the Beach was referred to as ‘the hostile takeover’ and who better to be a part of a hostile take over than the president of the company? Now you’ve not only have Hulk Hogan and Kevin Nash and Scott Hall, these powerful wrestling characters known all over the world, who were coming in ostensibly to take over the WCW, but the guy who is running WCW for Turner Broadcasting decided to turn against his own company and it made sense.”

Playing this new villainous role, Bischoff says, gave him the opportunity to amplify what he thought the perception about him within the industry and from fans was. If they thought he was a smarmy interloper, he was going to give them one.

“By the time I was front and centre as an on-camera talent in AWA, the underlying, I guess, vibe of me was, ‘Who the hell is he? He has never been in the wrestling business before’ or ‘He’s never put on a pair of boots. He’s not the son of a wrestler. Why is this guy even out there?’” Bischoff said. “There was a natural kind of dislike for me because I was an outsider who made my way into the business in a very visible, high-profile manner and the wrestling audience, the real core audience, resented that and resented me for it. Plus, I looked like a weatherman on a local television station. I had that Ken doll, kind of artificial weatherman look to me, which only made it easier for me to get people to hate me, so I just turned the volume up on all of that. My own personality, because I can be an outgoing, kind of over-the-top character and performing is something that came pretty natural to me so it was very easy for me and it was just a ton of fun.”

As part of his 83 Weeks podcast, Bischoff goes back and looks at old Nitro episodes and PPVs and gets a kick out of seeing himself now years removed from that run.

“It’s really weird when I go back and I watch stuff that I’ve done on camera because I feel like I’m watching someone else,” Bischoff said. “I’m so far removed from that character and from that time that and I appreciate it for what it is, but not to sound like a complete jackass, I was really freakin’ good at what I did. So I find myself chuckling at the character I played on TV and kind of admiring him from a distance, but I look at that character as a different person and sometimes forget that it was actually me.”

The good times, of course, wouldn’t last forever. Over the next few years, the NWO would splinter into different offshoots and bloat with superfluous membership, dragging down what was once a red-hot angle. On the backs of Austin, The Rock and Mick Foley, the WWF roared back to life as the pendulum in the Monday Night Wars swung firmly towards Stamford, CT. Big changes behind the scenes meant WCW began to feel the effects of the Turner-Time Warner merger. Bischoff says the signs were there that things were changing quickly in WCW.

“Once Time Warner came along, Turner started becoming run more like a bank or a law firm than a television company and it began to rear its ugly head in, probably August of ’98, when it first became painfully apparent to me,” Bischoff recalled. “I was in a meeting with probably 15 people who I’d never met and, out of those, 12 people who I’d never even met before, nor would I even know who they were, began to tell me how I should be operating creatively. Operationally, if they would have had things they wanted to do differently, I wouldn’t have had an issue with that but when I have people who didn’t even watch wrestling, didn’t know anything about wrestling, certainly didn’t know anything about WCW and where it had come from and where it currently was and how it got there, telling me creatively how I should be producing wrestling and trying to tell me that I should go back to doing what the WWF was doing while I was kicking their ass. It made no sense to me and I knew I was in trouble then. I knew WCW was in trouble then.”

Despite the realization that it was time to take his leave, Bischoff stayed put against his better judgment.

“I went home after that first meeting and had sat down with my wife and said, ‘Okay honey, I know I’m under a three-year contract and that’s wonderful and we’re making a lot of money and that’s wonderful, but I don’t want to do this anymore. This is not going to work out,’” Bischoff said. “And I talked myself out of resigning. I wish I wouldn’t have, quite honestly. Looking back, it’s one of the things I really regretted. I’ve always relied on my instincts first and then my thought process second, because my instincts are usually more accurate and I knew WCW was in trouble. I didn’t feel good about the way things were going to go. I wasn’t sure that I would be able to manage myself or WCW in this new environment and I was ready to walk away and I talked myself out of it. I started thinking about it instead of listening to my instincts and talked myself out of it. Unfortunately, I was more right initially than I thought I was.”

As the NWO petered out for good and the WWF’s hold on the industry tightened, Bischoff was let go from his management position by Turner in the fall of 1999 (he would briefly return as an on-camera character in 2000) and WCW would close its doors for good in March of 2001, sold to the WWF.

In the time since his WCW departure, Bischoff spent a few years as on-camera talent with the WWE in the early 2000s before joining Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (now known as Impact Wrestling) from 2010 to 2014. In the summer of 2019, Bischoff returned to the WWE as the executive director of SmackDown, but his time in the role was short-lived, exiting the promotion again that October.

Now 66, as far as Bischoff is concerned, his days as a full-time employee of a wrestling company are over.

“I’m really comfortable where I am at mentally, emotionally and financially,” Bischoff said. “More than anything else, it’s not because I don’t love the idea of being in the industry again. The idea of it? Sure. The idea of being back and the idea of having the ability to kind of communicate and affect some of the things I think are missing? Of course, I would love to do that. Part of me will always want to do that at the drop of a hat if it was the right opportunity. But there’s a much larger part of me, at this stage in my life, that says ‘Eh, I hate traveling.’ If I never have to get on another plane for the rest of my life, I’d be good with that.”

With his podcast and other business ventures, Bischoff is content with making sporadic appearances for both the WWE and All Elite Wrestling.

“I’ve done three or four appearances on Dynamite; I do work with WWE all the time,” Bischoff said. “I’m going to be doing more work with WWE at the end of this month. I guess I have the luxury of working with both companies and being able to put my toe in the water, get out in front of a camera again and kind of experience that shot of adrenaline. I enjoy that, but the thought of having to travel every week and deal with it, no, I don’t miss that at all. It would take an unrealistic opportunity; it would take a fantasy opportunity to get me to change my mind.”

As for why nobody has been able to capture the lightning in a bottle of the NWO, despite many, many attempts to recreate it in virtually every major promotion, Bischoff says the answer is simple.

“Because they don’t have a story,” Bischoff said. “Because nobody has really figured out why it worked. That’s one of the issues that I think exists today in wrestling is that a lot of people are throwing a lot of things up against the wall, but there is no real story behind it and what little story is there is so paper-thin that it doesn’t register as a story to the audience. It registers as a story to the people in the office kind of throwing that stuff up against the wall. They convince themselves there’s a story behind it, but their ability to convince themselves that there’s a story behind it doesn’t translate to the audience because they don’t see it. They don’t understand the psychology of why it works and they don’t think about the psychology of why they do most of the things we see on television. I mean, that’s being very critical – it’s being very honest, but also very critical.”

Looking back on his body of work in the industry, Bischoff knows what he hopes his legacy will be: “Innovation.”

“Having the courage to dramatically change the way the product was presented,” Bischoff said. “I would hope that people who really study the industry recognize that were it not for Nitro, were it not for the innovations and many of them controversial. When I [made the Nitro broadcast] two hours. We went live every Monday night back when WWF was taped. Everybody thought I was crazy, but I knew we had to be different. I knew we had to do something different in order to grow the industry and as much criticism as I took for that, going live, because it’s more expensive. That was that criticism. ‘Eric is just spending Ted Turner’s money’ was another one of the false narratives that were so prominent at the time.

“When I did something as silly as giving away WWF’s finishes [on Nitro] because I was live and they were taped, that was unheard of and I got a lot of heat for that. Nobody did it, but it worked. Bringing Lex Luger out [on Nitro in 1995] and surprising the audience with Lex Luger when everybody, including Vince McMahon, thought he was under [WWF] contract – controversial as hell! That’d never done before. Introducing the cruiserweight division. Nobody ever did that before. Bringing over on a regular basis – not as a one-off here and there – Hispanic wrestlers from Mexico and giving them a featured position in prime time. That had never been done before. The level of interaction that we had with New Japan Pro-Wrestling had never been done before. Sure, other people had done one-offs once a year or twice a year, but not like we did. The NWO angle was one of the most successful angles in the history of the New Japan Pro-Wrestling [NWO Japan featured the likes of Masahiro Chono, Keiji Mutoh and Hiroyoshi Tenzan among others], financially and otherwise. Nobody had ever done that before. So there were so many things that we did that nobody else had ever done before, that all kind of in its own way and certainly in a combined manner, dramatically changed the industry in ways that we still see today and it all started with Nitro and I hope that people remember that.”

And if they don’t?

“If they don’t, well, that’s cool,” Bischoff said. “It’s not going to cost me any money and I’m not going to lay in bed thinking about it, but I like to think my legacy is one of innovation if nothing else.”