May 10, 2016

The lessons of Victory Day

Victory Day. You may have heard TSN’s Gord Miller and Ray Ferraro mention the Russian holiday during Monday’s coverage of the IIHF World Hockey Championship. And one of TSN’s producers was able to experience this important day on the Russian calendar first-hand.

They played hockey on Monday at the Yubileiny Sports Palace in St. Petersburg. The fourth day of this year’s World Hockey Championship showcased two games, but those were not the battles that people had on their minds.

May 9 was a national holiday in Russia and it made for a long weekend this year. It’s a time to look back, reflect and to hope those dark days of war never come again.

The crowd had a decidedly sombre mood to it. The music playing outside was much quieter. The legendary beer garden beside the arena had far fewer people at its tables and those that were there had certainly toned things down a bit.

Not far from the arena, people carried photos of the dead through the streets. The procession went on for miles, with more pictures than one can ever comprehend. The “March of the Immortal Regiment.”

All along the busiest street in St. Petersburg, they walked by the thousands. Up and down Nevsky Prospect, there they were – as far as the eye could see, all clutching pictures of the lost. Honouring family members most of them never got to meet. The dead are thought of a lot in this city. And there are many to be remembered.

The annual procession happens every year here on May 9 at three in the afternoon. On one hand, the entire day is a celebration - “Victory Day” - the anniversary of the end of the darkest days they’ve ever seen. Soldiers pose for pictures with younger people on the sidewalks, a rock concert pulses through Vosstaniya Square in the late afternoon and a glorious fireworks display along the river at night. These celebrations happen all across Europe – marking the anniversary of the end of the Second World War.

But there’s a somber tone as well. Much like a Remembrance Day ceremony, there’s a lot of silence to absorb. Some people didn’t march – they simply stood and pondered. Others attended religious services. Many more sat in parks, enjoying a sunny day off.

The Immortal Regiment procession is a mix of both those emotions. In some ways it’s a celebration - at the very least a celebration of people’s lives. The locals are proud to make that walk and although it’s attached to a brutal part of their history, it also reminds them that things are better now. A chance to honour, a chance to remember and a chance to be glad they live in better days.

We often forget about what took place in the Soviet Union. It’s not a matter of ignorance, it’s simply a lack of knowledge. It’s rarely taught in our schools at any level. While our children grow up knowing of places like Dieppe and Auschwitz, they rarely if ever are told of the atrocities in Minsk or Kiev.

Or in St. Petersburg.

In Canada, we talk about D-Day. About how our soldiers stormed the beaches of Normandy and helped stop the war to end all wars. We proudly boast of our Canadian boys - the toughest S.O.B’s of all the forces that landed in France. We laud their bravery and talk about how we helped win a war that wasn’t even our own, because it was the right thing to do. We regard those men - our men - as the greatest of heroes, and we damn well should do it more often.

My grandfather, Ross Charles Taylor, did what so many Canadians at his young age did at the start of the war. He kissed his mom goodbye, left home and hopped on a train to join the fight. He crossed the English Channel early on the morning of June 6, 1944. And at the age of 21, he watched his friends in the Regina Rifles Regiment die right beside him - many before their feet were even out of the cold Atlantic Ocean. More than 300 brave young Canadians never saw the sun set on that first night in the western edge of France. Another 5,000 died over the next two and a half months - until the Allies liberated Paris and the Normandy campaign ended. By the time the war ended next spring, over 40,000 Canadians were gone.

And it’s always been that sheer number of deaths that astound me.

More than 40,000 Canadians were killed - almost as many people that live in my hometown of Brandon, Manitoba. That’s hard to comprehend and I don't know how grandpa made it out alive.

And I’ll never know. He passed away a few years back and would never tell me anything about D-Day - or any other day of the war, for that matter. And after talking to many other veterans, I understand why he wasn’t willing to share his story with anyone. Most of them will tell you it was down to complete luck that they survived. The ones who made it out alive felt guilty that they did, while so many of their brothers didn’t. In most cases, the bullet hit you or the guy beside you. It was a coin flip.

That said, Canada was also lucky during the war. Unlike most of Europe, we civilians weren’t located on the front lines - which meant all of our casualties were limited to military personnel. It sounds morbid, but at least those guys had signed up for the job. They knew what they were getting into and they were fine with that. When grandpa kissed his mom goodbye that morning and boarded the train to Regina, he knew he might never see her again. His mother knew it as well.

But he knew the family he left behind was never in any real danger. And of course, that was part of the reason our troops went overseas - to prevent this horrible war from spreading to our shores. They succeeded. And because of that, there were no civilian deaths on our home soil. No bombs fell on our schools and churches. No Axis forces rolled into our towns.

That wasn’t the case here in St. Petersburg.

In April of 1941, Hitler announced his plan to occupy the city of Leningrad (the former name of St. Petersburg) by declaring, “Leningrad must be erased from the face of the earth… We have no interest in saving the lives of the civilian population."

As the Nazis began to push eastward, hundreds of thousands of rural Russians fled to Leningrad. They had nowhere else to go to escape the advancing Nazis. A big city seemed like the safest place.

In August, the Germans started a bombing campaign of the city - wiping out churches, hospitals, schools and food depots. And the citizens joined the beleaguered Soviet Army to try and save their city.

Frustrated by the staunch resistance of the Russians - particularly those innocent, everyday citizens that had joined the fight - Hitler then announced that, “Leningrad must die of starvation.” His German troops encircled the city - cutting off every route. Tragically, that meant cutting off all food supplies to the city’s 3 million permanent residents and refugees. As the bombing continued on water treatment plants and food processing facilities, St. Petersburg became a damaged island that nobody could reach.

The people of Leningrad were running out of supplies. What precious food that remained needed to be rationed. Those who had already lost family members would hide the bodies so the deceased person’s ration card wouldn’t be taken from the family, leaving a tiny bit of extra food for the remaining members.

Things got much worse with the unusually cold Russian winter of 1941-42. Forced to survive on less than 500 calories per day, the people took drastic measures. Crime escalated as people did all they could to feed their loved ones. Families traded house pets so their children wouldn’t have to see their own pets being eaten. Starving Russians were forced to eat the remains of those who had perished. As winter approached, many mothers were forced to make a horrible decision: decide which child would live, then gently let the others die.

The Siege of Leningrad lasted for nearly 900 days - the deadliest siege in the history of mankind.

By the time it finally ended in January of 1944, there were barely 600,000 people left in Leningrad – from a city of close to 3 million. The 2 million people that died here weren’t soldiers storming a beach in France. They didn’t volunteer to fight. They were families. Mothers and fathers, seniors and children, men and women. They were lawyers and nurses. Farmers and librarians. They ran daycares and cut lawns.

They were just like everyone back in Canada. And they were innocent.

Though there isn’t an official number, the best estimates done later concluded that nearly 1.5 million of the Leningrad deaths were from starvation alone – one of the worst ways imaginable to perish. Many more were killed by bombs that fell daily from the sky. Most were buried in mass graves in a cemetery near the city centre.

What happened here isn’t shared much in the Western World, and many have no idea of the sheer numbers of innocent people that were lost.

But they are not forgotten here in Russia. And especially not on May 9th.

Every year those pictures come out as the people gather at Nevsky Prospect. They walk shoulder to shoulder, not knowing the people next to them. But they know they’re there for the same reasons.

Officially, the Soviet Union lost nearly 20 million people in the Second World War - though the fall of communism saw many experts state that number may be closer to 35 million.

That’s the entire population of Canada. Gone.

Even as Team Canada hit the ice on Monday, I was again stunned by another reminder of the war. The team was facing Belarus - part of the former Soviet Union - and their coaches were wearing the Ribbon of St. George (similar to wearing a poppy in Canada). I tried to find some information on war-time Belarus so Gord Miller could mention what the ribbons stood for. And what I found was again astounding.

At the time of the Second World War, the area of Belarus was home to about 9 million people. By the end of the war, nearly a quarter of them were dead. Over two million people. One out of every four. Gone.

And much like St. Petersburg, most of them were innocent civilians - numbers impossible to fully comprehend.

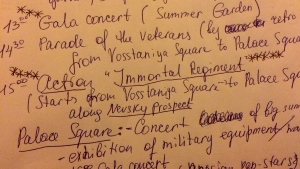

Leading up to V-Day, we tried to find out more information about the schedule of events for the ceremonies here in St. Petersburg. Our cameraman Dave Parker and I wanted to head out in the morning and get some video footage. We asked the hard-working young lady who brings the stats sheet to the commentators during each intermission and she returned with a handwritten schedule she translated off the city’s website. V-Day was just that important for her to go to all that trouble for us.

On that schedule, there was an asterisk beside the line that said “Immortal Regiment - 3pm.” She marked it as the most important event of the day. When I asked about it, she simply explained:

“Everyone in St. Petersburg lost so much of their families during this time. There’s far too many to remember. So this is the best way we can. We march with the lost.”

Was her own family affected? “Yes,” she replied. “Very much.” She then turned her head away from me.

As my grandfather once taught me, it’s mighty tough to talk about a situation that horrific. Even for her, a young lady about 20 years of age, the scars run very deep.

The next day, the focus returned to the battle on the ice. The music is cranked back up again and yes, those amazing Hungarian supporters (as well as many other fans) are back at the Beer Garden drinking the place dry. The streets aren’t full of people like they were the day before, but packed again with cars trying to make their way through that infamous Russian traffic.

Things had returned to normal. The pictures the people carried were stored back in safekeeping for another year.

Out of sight, but never out of mind.

Kevin Pratt is a long-time producer at TSN who works on the network’s International Hockey coverage, Season of Champions Curling and MLS Soccer.