Dec 3, 2014

Westhead: Bruce lawsuit claims CFL should have offered helmet to monitor for concussions

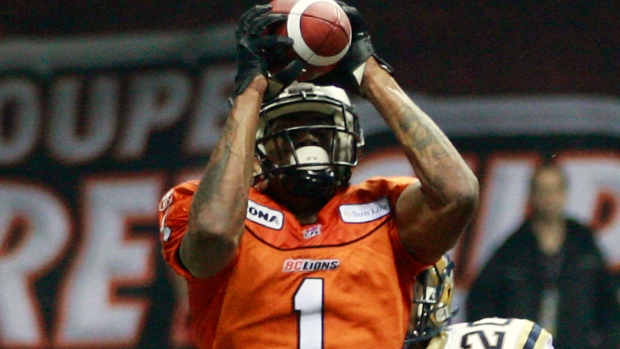

Former CFL receiver Arland Bruce has filed a lawsuit against the CFL claiming the league has not done enough to ensure its players are given the helmet sensor technology. As TSN Senior Correspondent writes, Bruce also alleges the CFL misled the public when it failed to discuss the long-term dangers of playing football after suffering repeated head trauma.

A state-of-the-art football helmet with built-in sensors that detect the number and severity of hits to the head a player receives during games has been thrust into the spotlight in a lawsuit filed by a former player against the Canadian Football League.

Former CFL All-Star wide receiver Arland Bruce claims in his lawsuit that the CFL has not done enough to ensure its players, particularly those who have already suffered concussions, are given the helmet sensor technology, which comes in Riddell's Revolution IQ HITS helmet, a model that sells for about $1,000 — more than double the cost of a typical helmet.

In new documents filed in a B.C. court, obtained by TSN, Bruce claims the helmet technology was used by the Calgary Stampeders' medical staff to convince former quarterback Dave Dickenson to retire in 2009 after suffering repeated concussions.

Bruce also alleges in court filings that the CFL misled the public when, during a public relations campaign about concussions, it failed to discuss the long-term dangers of playing football after suffering repeated head trauma.

In new pleadings, Bruce alleges a doctor working with the CFL misled the public when he released a study in 2012 claiming three of six brains of deceased CFL players they examined showed signs of the degenerative brain disease chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

The new allegations have not been proven and were included in legal documents filed in a B.C. court in response to the CFL's motion to dismiss Bruce's lawsuit against the league.

While the CFL has asked that the case be dismissed and sent to arbitration under terms of the league's collective bargaining agreement, Bruce argues he has a right to have his complaint heard in court because the league allegedly misled him and other members of the public, including peewee, high school and university football players.

The CFL is among several professional and amateur sports leagues under scrutiny for the advice it has given to players about head injuries.

Lawyers charge that leagues including the CFL, NHL, NFL and even NCAA have marketed violent hits and vicious plays and profited from them. The leagues have a vested interest, lawyers for some former players say, to return players to game action, even when it might not be safe for them to do so.

The leagues deny those accusations. The NHL, for instance, filed court documents last week in a separate lawsuit saying that, with the huge volume of information publicly available about head trauma, players should be able to "put two and two together" about the long-term effects of concussions.

Athletes who have gone to court have had mixed results. The NFL has agreed to pay an estimated $1 billion to settle a lawsuit filed by more than 4,000 NFL players.

The CFL declined to comment for this article.

On May 3, 2011, the CFL and its teams worked on a campaign to distribute informational flyers and posters about concussions to more than 100,000 athletes and coaches across Canada, Bruce's pleading says, adding the CFL wanted those flyers and posters on "every coach's clipboard, posted in every team's locker room, and available to every parent and player."

The flyers listed signs and symptoms of concussions and steps to follow before a player ought to return to action. "The player should not be left alone," was among the tips. "Regular monitoring for deterioration is essential."

But the flyers did not pass on advice about when players should stop playing football after receiving repeated concussions and advice had been available for decades, Bruce alleges.

A 1952 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine referenced in Bruce's lawsuit allegedly recommended players stop playing football after receiving their third concussion.

Bruce's lawyer says, in 2011, CFL Commissioner Mark Cohon pledged that the league would use a computer system to keep accurate records of player safety and health, would conduct baseline testing for concussions for all players, and would assess advances in helmet technology or any other innovation that would promote player health and safety.

Yet according to the pleadings, the Stampeders are the only CFL team using so-called helmet sensor technology.

The Riddell Revolution IQ HITS helmets "allow every football player on the field to monitor the number and severity of impacts received during game play," Bruce's lawsuit says. "The inner crown of the headgear is ringed with sensors that measure the number of hits to the head a player takes, what part of the head is contacted and the force of the impact."

The Stampeders, the legal filing says, have used the technology since 2008 and it has revealed that offensive linemen average 86 to 92 hits to the head during each game.

Bruce suffered a concussion and was knocked out during a September 2012 game in Regina. He was cleared to play that November and alleges in his lawsuit that he was still suffering from the concussion when he returned to the field.

"(Bruce) was not aware, advised, offered or provided with the opportunity to utilize the (Riddell helmet sensor technology) by the CFL, the B.C. Lions, or the Montreal Alouettes."

CFL teams should ensure players who have had documented concussions are given the expensive Riddell helmets, Bruce's lawyer Robyn Wishart said in an interview with TSN.

Some U.S. schools have adopted the Riddell helmet sensor technology already, including Virginia Tech, Florida State and Oklahoma. A study in January in the Journal of Neurosurgery found certain helmets can reduce the risk of concussion by at least 50 per cent.

Bruce is also suing Dr. Charles Tator, a prominent Toronto neurosurgeon and scientist, and CFL Alumni Association executive director Leo Ezerins.

The CFL based its 2011 public relations campaign, as well as its current concussion-related protocols, on research published by Tator and Ezerins. Wishart said Tator and others have ignored the 1952 study that recommended football players retire after three concussions.

Tator scoffed at that suggestion.

"They must have had a crystal ball in 1952," Tator said in an interview with TSN. "(The recommendation) certainly would not have been based on any science. It would have been a wild guess. Someone picked that out of a hat... Who was the author?"

TSN subsequently determined the 1952 study was authored by Augustus Thorndike, the chief of surgery at Harvard University from 1931 to 1962. Thorndike was among the first medical experts to advocate for doctors to be present at sports events, and, according to his obituary in The New York Times in 1986, also was among the first doctors to insist hockey players wear helmets.

In 2012, Tator and Ezerins published a scientific paper after they studied six brains of deceased CFL players and found CTE in three of them.

"How can you title your study 'The absence of CTE' when three in six brains studied showed evidence of CTE and the other three had Parkinson's, Alzheimer's and ALS?" Wishart, adding that publishing a study based on a sample size of six brains was "embarrassingly low."

By contrast, researchers at Boston University have published studies based on researching as many as 87 brains, Wishart said.

Tator told TSN that after starting research four years ago, he and his team have now studied 12 brains, and will release another report updating their findings. He wouldn't say when that report might be made public.

"The Boston group has gotten in the habit of calling a media conference every time they find (CTE)," Tator said. "We have a different style."

Tator said he's not beholden to the CFL.

He said his group receives about $500,000 per year in research funding from private donors, including the Weston Foundation.

The CFL, Tator said, has provided his team with less than $2,000 in total funding. "Any time we place an ad in the CFL Alumni Association newsletter, it costs us a few hundred dollars," Tator said.

In his pleadings, Bruce also raised concerns over a series of brain tests 25 retired Hamilton Tiger Cats players agreed to take in 2011 at McMaster University. The Hamilton Spectator newspaper was going to publicize the results.

After testing, Ezerins and Tiger Cats alumni president Dave Lane allegedly met with the school, which subsequently informed the Spectator it would not interpret the results.

The lawsuit claims Ezerins said at the time, "We are really protecting the CFL. It is a very important issue and we want to make sure it does not reflect poorly on the game of football; that we have the proper perspective."

The results later showed that 24 of 25 players scored below average in key brain function indicators, the legal filing said.

Ezerins said in an emailed statement that Bruce's allegations against him are "spurious and without any merit.

"The CFLAA is, for lack of a better description, a philanthropic organization, focused on assisting former CFL players, if we can," Ezerins wrote. "We make no claims as to possessing any kind of expertise, thus we do not provide advice or counselling."