Feb 16, 2017

Boudreau’s track record of beating the percentages

The performance of the Minnesota Wild this season fits into a larger trend of how Bruce Boudreau’s teams end up on the right side of shooting and save percentages, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

Does Bruce Boudreau influence PDO?

It’s an interesting question in light of what’s happening in Minnesota this season. The Wild are shooting lights out offensively and stopping just about every shot they face at 5-on-5. Season-to-date, their team 5-on-5 shooting percentage is 9.85 per cent (second best in the NHL), and their team 5-on-5 save percentage is 93.4 per cent (second best in the NHL). Their PDO – simply an aggregation of the two metrics – is, as you might have guessed, second best in the NHL.

Naturally, whenever a team goes on a PDO bender (be it shooting percentage driven, save percentage driven, or both), expectations are that regression will curb those numbers. It’s reasonable to expect that to play again here. Minnesota’s PDO – a 103.3 right now – has only been met or exceeded once in the NHL modern era, by Boudreau’s 2009-10 Washington Capitals.

Betting on PDO has historically proven to be the right play for this very reason. The NHL in the modern era is predominantly won, in the long-term anyway, on volume – something we are much more confident players and coaches can realistically influence.

It’s important to note that the two components of PDO operate differently. Shooting percentage is, in relative sense, much more volatile. Teams that shoot white-hot for a period of time will almost certainly regress towards league averages over the next interval.

Goaltending is a bit different. Most teams will regress sharply toward league averages, but that hasn’t been completely true at the poles. If you have a Henrik Lundqvist or Carey Price the chance of your team save percentage being higher than normal are reasonably strong. So while save percentage also sharply regresses, it won’t behave in the same manner as shooting percentage.

This brings us back to Boudreau. This year’s Minnesota’s team seems out-of-control lucky right now. But if you look at Boudreau’s track record across multiple teams, there seems to be something about how frequently his teams get the better of the percentages.

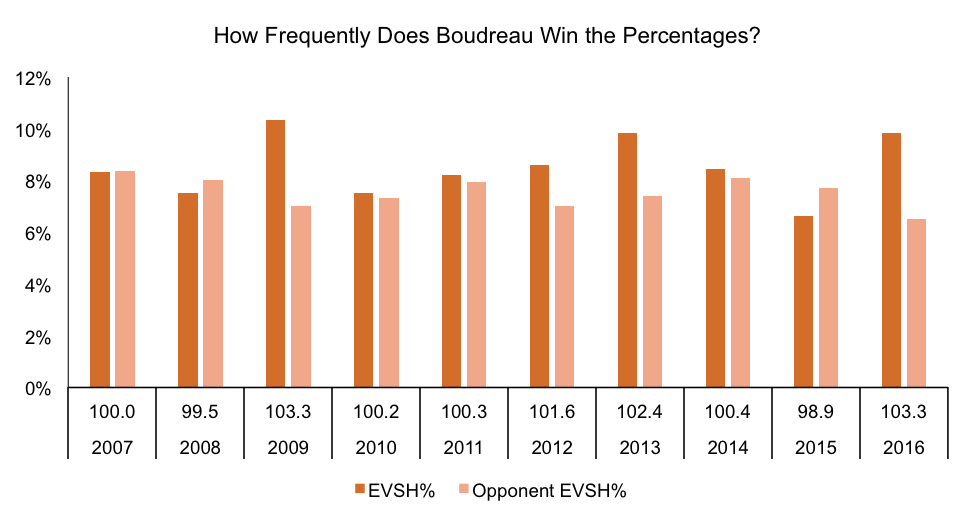

The horizontal axis shows the year Boudreau was coaching (be it with Washington, Anaheim, or Minnesota) and his team’s respective PDO in that year. A 100.0 PDO would be right around expectations – think of a team that shoots perfectly average at 5-on-5 (7.8 per cent) and a team that stops a perfectly average number of shots at 5-on-5 (92.2 per cent save percentage). Any number above is a team that’s gotten the right side of the percentages. Any team below has been burned by them.

Boudreau’s teams seem to fair awfully well here. Over this 10-year interval, Boudreau’s average PDO is about 101.0, which basically puts his multi-team output next to Boston in the Tuukka Rask/Zdeno Chara era (101.1 PDO) for tops in the NHL.

In the graph above, you can see that in just about every season, Washington’s converted on a better number of their shots than their opposition, and that’s been true in all three spots. Funny enough, the only time it really was variant in a negative manner – 2015 – Boudreau was fired, despite the fact that Anaheim won their division.

So not only do Boudreau’s teams generate a very favourable shot share, they also convert at higher rates. Put that together, and you have an obvious reason as to why he’s had so much regular-season success in his career.

The interesting thing with Boudreau and his teams though is that their generally fantastic PDO isn’t driven by just shooters or just goaltenders. Over this 10-year stretch, Boudreau’s teams shot about 8.5 per cent at 5-on-5, which is about 0.7 per cent better than league average. That means in any given season, his team was immediately +14 goals better on merely conversion rate than your average team. (An 8.5 per cent shooting percentage would be tops in the NHL over that span.)

Goaltending has also been a strength. Boudreau’s goaltenders across all three teams have stopped 92.5 per cent of shots at 5-on-5, which is 0.3 per cent better than your league average team during that stretch. That’s right around top-5 in the NHL over that span, trailing only the likes of teams with Rask, Price and Lundqvist.

I find the data fascinating here. Some time ago, hockey people subscribed to the idea that while PDO and regression is a very real thing, the band to which teams regress is not perfectly equal. Generally, we have found this to be true when discussing clubs with entrenched, Hall of Fame-calibre goaltending.

But maybe, just maybe, Boudreau has a similar impact on his team. After 10 years, thousands of games and tens of thousands of shots, Boudreau’s teams simply see the puck go in with more frequency than their counterparts. While I don’t subscribe to the idea that any team could replicate what Minnesota has done over the first 50-or-so games, I do wonder if Boudreau’s system is adding a couple of wins here and there over the season because it lends itself well to getting to dangerous shooting areas (and avoiding them in the defensive zone).

Something to consider as Minnesota’s crazy run continues.