Jun 10, 2016

Howe’s career was one of a kind

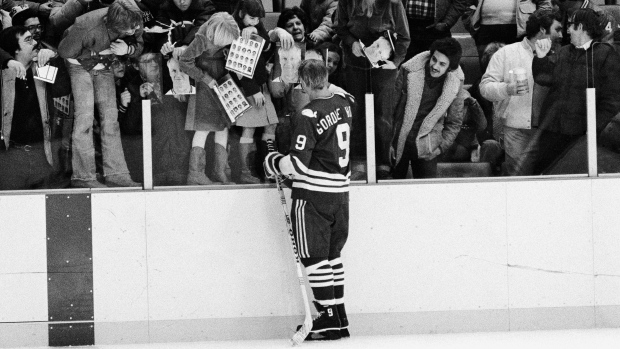

Mr. Hockey was the sport’s greatest all-around player, capable of intimidating via his talent or his toughness, Bob Duff writes.

Perhaps the most shocking element of Gordie Howe’s death is that it actually happened. It seemed as if Mr. Hockey would go on forever.

He certainly did as a player.

People marvel at Howe’s majestic, Father Time-defying legacy, but it isn’t his longevity that should be celebrated as much as his incredible productivity over such an unmatched period.

Howe, who died Friday at the age of 88, broke into the NHL in 1946 at the age of 18 and was still performing effectively in the league at the age of 52. In 1979-80 with the Hartford Whalers, Howe, who’d been eligible for AARP benefits for two years, played every game and scored 15 goals, more than twice as many as the seven he scored as a rookie with the Red Wings in 1946-47.

“My last year in the NHL, with Hartford in 1979-80, I played all 80 games and I was 52,” Howe recalled proudly.

Take a moment to consider that. During the 2014-15 NHL season, only 74 of 886 players skated in every one of their team’s games and just 18.6 per cent (165 of 886) reached the 15-goal plateau.

And none of them were playing their 33rd pro season.

“They ought to bottle his sweat,” Hall of Famer King Clancy once suggested of Howe. “It would make a great liniment for hockey players.”

The numbers Howe put up during his unparalleled career are astonishing. He won six NHL scoring titles, bettering or equalling the NHL single-season scoring record in three consecutive seasons between 1950-51 and 1952-53. His games played (1,767) goals (801), assists (1,049) and points (1,850) totals are all NHL records for a right-winger.

Howe scored 20 goals or more every season between 1949-50 and 1970-71, an NHL record. He finished among the league’s top five scorers in 20 consecutive campaigns, another league mark.

He delivered his most productive NHL season with 103 points in 1968-69 at the age of 41. Howe remains the only player in league history to record a 100-point season in his 40s.

Howe was 42 at the end of the 1969-70 season. At that point, Toronto centre Murray Oliver was the active NHL leader in consecutive games played with 240. Howe was next at 233, a streak he extended to 252 games before suffering sprained rib cage and torn cartilage in a collision with Philadelphia defenceman Joe Watson after scoring his second goal of the game in a 4-2 win over the Flyers on Nov. 22, 1970.

He was an MVP in three different decades, winning four Hart Trophies in the 1950s with Detroit and two more in the 1960s, the last coming in 1962-63 at the age of 35, when Howe also led the NHL in scoring for the final time.

Ending a two-season retirement to play with sons Mark and Marty on the WHA’s Houston Aeros in 1973-74, Howe recorded a 100-point campaign and was named the league’s MVP. He was 45.

The Wings had buried Howe in a meaningless front-office position while the competitive fires still smoldered within this legendary player and Howe jumped at the chance to get back on the ice.

“My exit wasn't on a high note,” Howe said of his treatment by the then-woeful Wings. “The team wasn't going anywhere and I didn't just want to hang on. Then somebody put the love back in the game, when they got Marty and Mark to play with me.

“My greatest thrill is still when I returned to hockey (to play on the same team with my sons.”

Marty Howe admitted that the family feared for their father’s well-being when he opted to return to action in middle age, but soon discovered it was others who should be worried about Gordie.

“Our first exhibition game was in Greensboro (N.C.) against the Los Angeles Sharks,” Marty recalled. “Gordie was in the starting lineup and as the puck dropped, the winger opposite him drops his gloves and says, 'OK Howe, let's go.'

“Gordie just took his stick and hit the guy in the head. They both got majors.

“They come out of the penalty box and the guy drops his gloves again and says, 'OK, Howe, let's see what you got,' so Gordie cuts him up again.

“This time, they get majors and misconducts. By the time they're out of the box again, it's nearly the end of the second period, but this guy hasn't had enough yet.

“Well, Gordie could see this guy wasn't going to give up, so he just took his stick, wound up and cracked the guy right across the head. They both got tossed.

“That was Gordie's first game in the WHA.”

His soulless ambivalence for the opposition was as much a part of Howe’s legend as his world-class skill.

“One thing about the old man,” Mark Howe said. “You never had to worry about him.”

“He's absolutely the nicest guy in the world off the ice, but once he put that uniform on, look out,” Marty said of his father. “I'm just glad I never had to play against him. Practice was bad enough.”

In a dog-eat-dog world, Gordie was the big dog.

“To survive in the NHL, you need to carve out a foot of ice around you as your personal space,” Hall of Fame defenceman Pierre Pilote explained. “Gordie carved out three feet for himself and no one dared venture into his space.”

Superstars. Journeymen. Rookies. It didn’t matter.

All felt Howe’s wrath if he felt they wronged him.

“My second game with Indianapolis in the WHA was against New England,” remembered Wayne Gretzky, who on Oct. 15, 1989 surpassed Howe to become the NHL’s all-time scoring leader. “I saw Gordie during the warm-up and he was smiling and winking at me.

“When the game started, we were both on the ice. Gordie had the puck, but I snuck in behind him, stripped the puck off his stick and started heading the other way.

“I'd taken about two strides when all of a sudden, I felt this sharp pain in my thumbs. Gordie had whacked me across the thumbs with one arm, spun me around with the other and took off with the puck.

“After a whistle he skated by and said, ‘don't ever embarrass me on the ice again.’”

It’s a given that Howe was hockey’s greatest all-around player. He was the game’s most complete player, capable of dominating any style of game you might choose to play. He could intimidate via his talent or his toughness.

If you needed someone to fight, Howe could take care of that. If you needed a scorer, he did that. If you needed a checker, Howe was strong enough to shut down anyone. He could even play defence in a pinch.

“The only thing Gordie Howe can’t do,” Montreal GM Frank Selke once said, “is sit on the bench.”

Howe dictated how the game would be played and he was capable of doing this over a five-decade span.

Through it all, it never went to his head. Howe was always accessible and even years after he skated in his last game, remained hockey’s greatest ambassador.

Mark Renaud was a rookie defenceman with the Whalers in 1979-80 and got to skate alongside Howe in his farewell NHL season.

“He was really incredible,” Renaud recalled. “I wasn't sure what to expect when I got there. I wasn't sure how good he still was. Boy, did I find out in a hurry. He more than carried his weight.

“Plus, he was like one of the guys. No special attention, no pretensions. He was unbelievable.”

What is truly amazing is how close it came to never happening.

At the age of 15 in 1943, Howe attended training camp with the New York Rangers.

“I was there four days,” he recalled.

Rangers GM Lester Patrick sent Howe home, advising him to give up on hockey and pursue a trade.

A year later, the Wings brought Howe to camp and assigned him to their Galt junior club. After one year of minor pro with Omaha of the USHL, Howe came to camp with the big club.

Tommy Ivan, who’d coached Howe in Omaha, had been promoted to run Detroit’s AHL club in Indianapolis.

“He’ll be playing for you this season,” Detroit coach-GM Jack Adams told Ivan, pointing out Howe on the ice.

“No,” Ivan answered. “He’ll be playing for you.”

Ivan was right. Howe played for the Wings for the next quarter-century, rewriting the NHL record book.

But even for the game’s immortals, the end must come.

“We can’t all play forever,” former NHLer Adam Graves remarked as his career was winding to a close. “There’s only one Mr. Hockey.”

Howe’s career was one of a kind. His legacy was unsurpassed; his contributions to hockey unmatched.

He will live on in the hearts and minds of those who love the game as long as the game is played.

Bob Duff is the author of Nine: A Salute to Mr. Hockey