Oct 13, 2016

Pitch-framing gives Jays advantage

TSN Baseball Analyst Dirk Hayhurst takes a look at what it is that Blue Jays catcher Russell Martin does behind the plate to ensure his pitchers get the calls they're looking for from the home-plate umpire.

There is a lot to like about Russell Martin. He’s a good leader behind the dish, handles his pitching staff well, hits and has plenty of big-game, postseason experience. In fact, a large part of why this 2016 Blue Jays pitching staff is so good is because Martin is so good at handling them and framing their pitches in the best light.

Pitch-framing isn’t a very well understood art. Mostly because we, as fans watching a game, only see one aspect of it—where the ball ends up. But there is a lot more to it than simply catching the ball in the flat strike zone we perceive on our television sets.

Before we can actually describe how Martin frames pitches, we need to understand that the zone is a volume of three-dimensional space, not a flat, 2D box into which a ball must travel. Because of that, a catcher can actually catch balls inside the strike zone by going into this volume of space from the back and from the sides. Therefore, how Martin frames pitches starts with the fact he’s not actually using a frame (a flat rectangle), but a cube.

Sounds complicated, but it’s really not. If the strike zone is a cube and the ball passes through it on it’s way to the catcher’s mitt, then the catcher doesn’t want to move behind the cube like he’s on a set of rails and can only move laterally, like a player on a foosball table. He wants to move around the space - rotating around it - on a crescent. He wants the pitcher to intersect it with his pitches (to the limited degree a pitcher can) and make sure the umpire sees it.

To facilitate this, whenever Martin sets up, he’s showing his pitcher a target that is generally outside of the zone. Thus, when he reaches forward, he is always reaching toward the volume of the strike zone instead of toward the pitcher.

Remember, the pitch must travel through the strike zone to be called a strike. Some pitches will only nick the corner of it before running, cutting or breaking out of it again. If a catcher’s angled his body towards the strike zone, he can reach out and receive the ball in the zone (if it’s breaking hard, like a sinker from Aaron Sanchez) or let the ball travel deep into his mitt (like a fading changeup from Marco Estrada). Essentially, this approach allows a catcher the ability assist the ball in touching the strike zone volume. If the catcher simply moves side to side, the further away from the strike zone he got, the smaller the chance the flight path of the ball would ever intersect with the zone, even if it hit the mitt dead-on.

Now, an umpire should call a pitch that touches the zone, no matter where it ends up. A strike must pass through the zone, but it doesn’t have to end there. But watch enough games and it’s clear to see that many pitches that touch the zone get called balls, while many that skirt it get called strikes. You can thank your catchers for that.

A good catcher “helps” the umpire see that the pitch was in the zone by catching it with ease, grace and - above all else - in such a manner that insists the ball touched or completely passed through the strike zone.

That, however, is easier said than done.

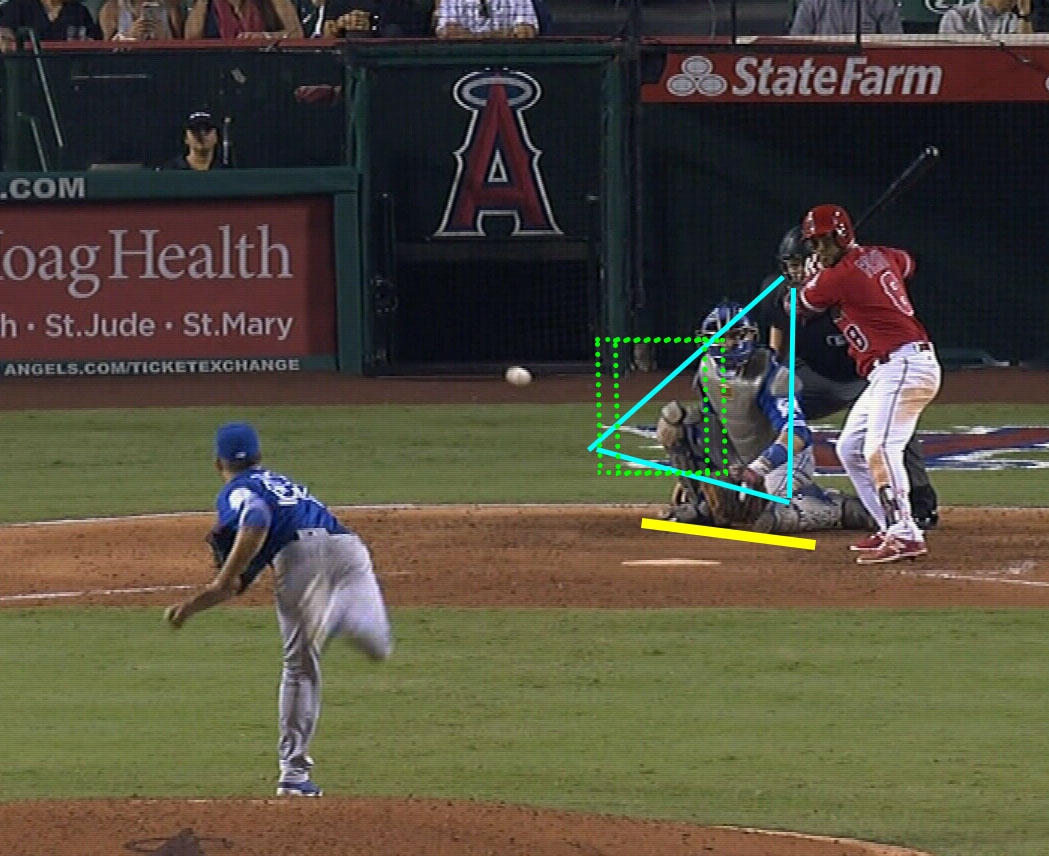

Let’s take a look at this picture:

See where the umpire is? He’s behind Martin, between him and the batter, looking down over the zone. He’s not directly behind it. So, even if he did use an imaginary frame, he wouldn’t even be standing behind it.

The umpire's perception of the strike zone is at an angle. Thus, to help the umpire see the zone, the pitch, and the reception point better, Martin angles his body so that he’s aligned more with the centre of the strike zone than the pitcher, and compresses himself for a good line of sight.

Below is an illustration of what I'm talking about. Martin’s set up inside, and angled toward the plate. This is not for the pitcher, but for the umpire, who is floating over his shoulder, using him like crosshairs to see the flight path of the ball. If Martin set up parallel to the rubber, the umpire might feel pushed further away from the plate and it would be more difficult for him to distinguish the flight path of the pitch and whether it crossed through the zone.

However, because Martin is angled and on a knee with his shoulder down, the umpire gets the best view of the zone. If he were taller, like Salvador Perez, the umpire's view might be blocked. Height may not measure heart, but it can impact Called Strikes Above Average (CSAA), a method some analysts use to measure a catcher’s ability to turn borderline pitches into strikes.

You’ll also notice in this picture the “pre-pitch movement.” Look where Martin’s glove is here. It’s down, not even in the zone. It’s going to come up into it, of course, and even take a high pitch and turn it into a strike (check the video). However, by starting down and out of the zone, Martin creates the effect that, when he reaches for a pitch, he’s reaching into the zone.

You might think this bothers the pitcher, what with the catcher moving his glove down out of the zone, but, if you look in the video above, you’ll notice that Martin sets a target early, usually at the bottom of the zone, then drops the mitt and then extends to receive the ball in the zone—that's for the umpire.

Martin has a really solid understanding of all of his pitcher’s “pitch lanes.” That’s a fancy way of saying, he knows how his pitcher’s pitches will travel and their natural movement - a knowledge he’s acquired from working with them for so long. He knows that he doesn’t even have to set up in the strike zone in order to receive a strike from his pitchers on account of their pitch action or “lane” action (unless they're struggling to find the zone, of course, then watch how he makes the zone smaller).

Finally, and maybe the most easy thing to spot, there is his mitt curl or glove work after he receives the pitch. He takes pitches that are on the corner and “sticks” them with a slight curl of the mitt, always towards the zone. This way, if a pitch was on the border, the curl makes it appear as if the ball was heading into the zone or was already there. Remember, the umpire doesn’t see what we see on television. He doesn’t see where the ball entered the mitt - he only sees the mitt take in the ball. The ball could be on the strike-zone side of the mitt or the ball side of the mitt. A little curl helps confirm more strikes and fewer balls, even though the umpire can't be totally sure.