Aug 23, 2016

The inexact science of building an NHL roster

The Blackhawks and Predators differing approach to no-movement and no-trade clauses shows there’s more than one way to assemble talent, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

One of the interesting wrinkles in newer versions of the NHL’s collective bargaining agreement has come from no-movement and no-trade clauses – mechanisms that protect players from being sent to undesired locations at any period after signing their Standard Player Contract (SPC) with a given team.

The no-movement and no-trade clauses have become hot-button topics given the NHL’s decision to expand to Las Vegas, and the decision the league and players’ union had to reach in determining whether certain player movement restriction clauses protected a player from an event like an expansion draft. (Ultimately, both sides agreed that no-movement clauses would shield a player from exposure to such an event. No-trade clauses, however, will not enjoy the same protection.)

What is most curious about these player incentives is how certain organizations have used them as a carrot of sorts, frequently embedding the clauses in their SPCs without so much as batting an eyelash. Other organizations have frequently shied away from utilizing them, only executing on no-movement or no-trade clause in the most needed circumstances.

There are trade-offs in both instances. In the first example, teams are more likely to attract talent by way of stabilizing their future – the clauses can either partly or wholly guarantee a player’s tenure in a specific city, which means they serve as an excellent over and above incentive, especially for players deciding between multiple contracts of comparable base salary.

On the other hand, teams who frequently use these clauses tend to find themselves in a bit of a bind at the trade deadline or in free agency periods. With each incremental no-movement or no-trade clause comes less roster (and financial) flexibility, which has very real value. The teams that tend to balk at giving away such clauses generally operate in a more elastic environment – one in which struggling players can be dumped to clear roster space, or prized assets can be flipped to the highest bidder for the best package available.

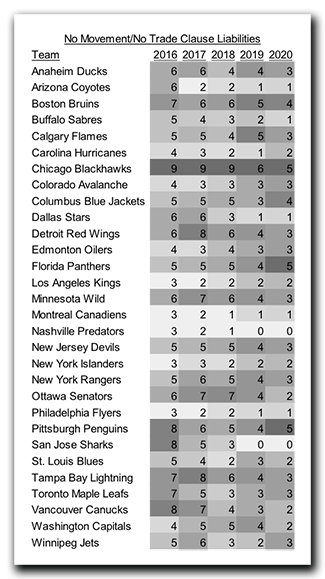

The discussion around these clauses had me curious about the type of liabilities teams currently have on the books and what the landscape looks like over the next few years, so I pulled in all known no-movement and no-trade clauses (both modified and full) to get a feel for the breakdown.

It won’t come as a surprise that teams like Chicago and Pittsburgh have made liberal use of such clauses, but there are a number of other teams in fascinating positions. (Data via GeneralFanager and CapFriendly.)

The table is done as a heat map, with the darker the colours indicating increased no-movement or no-trade clause liabilities. As expected, perennial contender Chicago – who, under general manager Stan Bowman, have frequently incentivized players to sign with such clauses – have a ton of player movement restrictions. For just next year alone, that list includes Brian Campbell, Niklas Hjalmarsson, Duncan Keith and Brent Seabrook on the blueline, and Artem Anisimov, Marian Hossa, Jonathan Toews, and Patrick Kane up front. Goaltender Corey Crawford also has a no-movement clause.

The Chicago template is a great example of how this strategy can be pretty hit or miss. Landing first-pairing talent Campbell on a one-year, team friendly $1.5 million contract was one of the best moves of the summer, so naturally there would be some sort of stabilizing offset to benefit the player. In this case, Campbell was given a no-movement clause. On the other hand, you have a player like Brent Seabrook, whose production has started to taper off in Chicago. His eight-year, $55 million contract may not be poisonous today, but the future doesn’t look great, and it’s likely the Blackhawks will be in tough to get out of his deal.

On the other side of this discussion is a team like the Nashville Predators, who are quite obviously reluctant, relative to league norms, to award movement restrictions to players. Only goaltender Pekka Rinne and winger James Neal carry player restriction clauses beyond the 2016-17 season, and even both of those are modified in nature – a way to mitigate unilateral player control in the event an organization is preparing a trade. (And no, Shea Weber – recently traded to Montreal – did not have any type of clause in the contract he eventually signed with the Predators.)

Speaking of the Habs, they are similar to the Predators in this sense. They parted ways with one of the players who did have a restriction set to kick in this summer in P.K. Subban, and are now left with just Jeff Petry’s modified no-movement clause on a long-term basis. (It must also be noted that the Habs have less long-term commitments than the Blackhawks, which means some of this is borne out of sheer probability.)

From top to bottom, I don’t think there’s a clear relationship or distinction between team success and the frequency with which teams utilize these clauses. Teams like the Blackhawks will enjoy the signings more so in the short term, while teams like the Predators – who suffer more financially with poisonous, unmovable contracts, and should theoretically be more risk averse – own significant control over shaping and crafting their roster in the long term.

Two different strategies, two very talented teams. Just another example in how roster building is far from an exact science.