Aug 9, 2018

The Trade: 30 years later

It was 30 years ago on August 9, 1988 that the Canadian sports world was turned on its ear when the Edmonton Oilers did the unthinkable and dealt Wayne Gretzky to the Los Angeles Kings.

, TSN.ca Staff

Most people only experience a handful of “Where were you?” moments in their lifetimes, but you can remember them vividly, like they were yesterday.

One such moment happened for hockey fans in the summer of 1988.

It was Aug. 9. I had just turned six a few days earlier and I was in Brampton, Ont. My family had returned from an ill-fated RV trip to Algonquin Park and Quebec City. My most vivid memory of that voyage was the RV’s septic tank backing up and spewing waste all over the tiny bathroom. I found it funny. Nobody else did.

As I waited at my aunt and uncle’s for my father to return from bringing back the RV, my mother came into the room to let me know that Wayne Gretzky had been traded.

I didn’t really understand. Wayne Gretzky was the Edmonton Oilers. How was that even possible? You can’t trade him. It must be a mistake.

Grant Fuhr was on The Rock when he heard about it and he, too, didn’t understand.

“I was out at Bob Cole’s golf tournament in Newfoundland with Marty [McSorley,]” Fuhr said. “Somebody came out to the golf course and told us they traded Wayne and we didn’t believe him. At that time, we all thought it was a joke. We never thought that Wayne would ever be traded.”

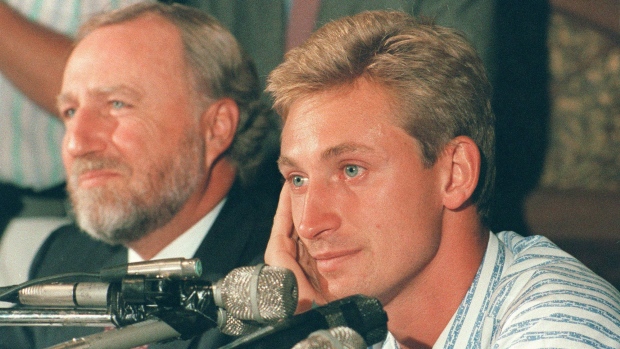

“The Trade” was real. On the afternoon of Aug. 9, 1988, Wayne Gretzky, Marty McSorley and Mike Krushelnyski were traded to the Los Angeles Kings for Jimmy Carson, Martin Gelinas, first-round draft picks in 1989, 1991 and 1993, as well as $15 million in cash.

Canada’s most iconic sports figure – perhaps ever – would now ply his trade in the United States. Fresh off of a fourth Stanley Cup triumph in five seasons, Gretzky was headed for the west coast.

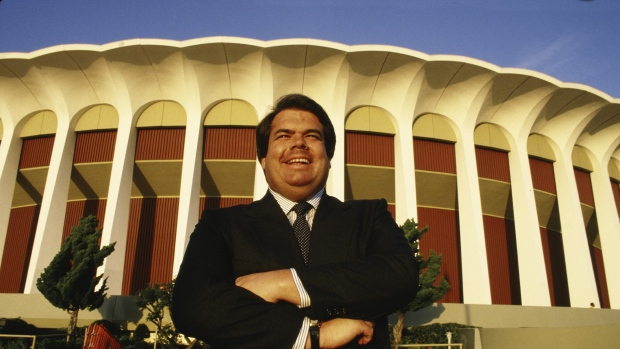

The move that sent shockwaves across the country didn’t happen overnight. The mastermind – Kings owner Bruce McNall – had been engineering the move for months. McNall’s pursuit of Gretzky wasn’t made with just a Stanley Cup in mind. It was made to save the Kings.

“It wasn’t so much the team issues, it was the lack of general interest in California - in L.A. specifically,” McNall said. “It’s just that nobody gave a s**t. It didn’t matter if we went to the playoffs or not because nobody knew and that was the thing that bothered me the most.”

A coin collector and movie producer, the charismatic McNall came on board with Kings ownership in 1986, when he bought a 25 per cent stake from Lakers owner Jerry Buss. By 1988, McNall owned the team outright. A native of nearby Arcadia, CA, McNall knew that the Kings would always play second fiddle to their Great Western Forum arena-mates, the Lakers. That was fine, but the team was on the verge of becoming a complete nonentity in the market with its viability coming into question.

“We were getting in six, seven, eight thousand people a night,” McNall said. “It was not making money. It was basically breaking even and we didn’t have any really big talent and from the team’s standpoint. I was excited because in ’87 we had three young All-Stars and Luc [Robitaille] winning the Calder Trophy in ’87. Steve Duchesne and Jimmy Carson were also on the All-Rookie team, so I felt we had a really cool, young team, but nobody cared.”

The Kings were trending upward led by that trio, but success had been hard to come by in a division with the juggernaut Oilers and the powerful Calgary Flames. After a 68-point season, the team fell in five games to the Flames in the Smythe Division semi-finals. The Kings had not won a playoff round since 1982.

But for the diehards, there was reason for excitement. Carson, 19, had just scored 55 goals as a sophomore. Robitaille, 21, had 111 points.

Carson was excited about the team’s future.

“Bruce McNall had contacted me and said we want to renegotiate your contract and sign you to a longer- term deal,” Carson recalled. “I said, okay, maybe I will buy a house and he said sure. And actually it sounds kind of funny now, but his wife at the time, Jane, was an interior decorator. He said he would even have Jane help me with the interior stuff, which she did. I bought a home in Redondo Beach and got it outfitted and his wife helped me outfit it and it was beautiful. I got traded a month later.”

McNall first floated the Gretzky idea to Buss back in 1987, knowing that it would seem preposterous. You can’t just go get the sport’s best player. It doesn’t work like that. These things don’t happen.

Beginning with the general managers’ meetings in December of 1987, McNall began a campaign to make his pipe dream into reality.

“What happened was, I’d spoken on the phone continuously to Peter Pocklington, the [Oilers] owner at the time, and I would speak and I would bug him about it,” McNall said. “‘Hey, how about Gretzky?’ and he’d laugh and say, ‘Give us the whole team’ and then he’d laugh and say, ‘I [still] wouldn’t trade him.’ I said, ‘I will give you the whole team’ and he’d laugh and say don’t be ridiculous. Then every time we went to the board meetings, five or six meetings a year, and I would see Peter once again, I would bug him. Then, out of the blue one day, he called me and he said, ‘If you are still serious about Gretzky we can talk.’”

This became a singular pursuit for McNall with no fallback in place.

“There was never any other plan,” McNall said. “There was no other plan because, frankly, there’s no person - and that includes today, by the way - that sells hockey tickets…I mean, how many people actually buy tickets to see ?

Some, but not a lot in my opinion. How many go for [Alex] Ovechkin? I don’t think any - maybe some, but I doubt it. They care about winning and losing. In Canada, of course, it doesn’t matter if you win or lose - look at Toronto. They’ll sell out regardless of the team, it doesn’t care. But in L.A., it’s not the case and winning and losing wasn’t even the issue. You know, there was no culture to allow it and that’s why I decided that the only plan was to see if I could find a way to get Gretzky, which seemed ridiculous, frankly, at the time.”

When Pocklington finally got serious, the price was expectedly exorbitant, McNall recalls.

“He said, ‘Well, first of all, I want $15 million U.S. cash,’” McNall said. “That was the first thing out of his mouth and I said okay, done. Then he said, ‘I want this to be a trade; it has to look like a trade. I need to get some players back and I need draft picks and players, blah blah blah.’ And I said okay. I said yes to everything and it was at that point that we got more into the nitty gritty.”

As McNall and Pocklington opened negotiations, one thing became crystal clear: Oilers general manager Glen Sather could not be involved.

“Pocklington didn’t really want Glen Sather involved because he knew what was going to happen,” McNall said. “He knew that Sather was going to go out of his mind. And eventually when Glen did get involved, he did go out of his mind. He said, ‘We’re not trading him! I don’t give a f**k what that owner thinks he can do; we’re not doing it!’ …It was pretty crazy and finally, I guess, Pocklington made some arrangement with him or did something with him and finally some sanity came about and we could actually discuss things on a more rational basis.”

As negotiations began in earnest, the Oilers made it very clear that they coveted Robitaille. With 45 goals in his rookie campaign, the Montreal native looked to be blossoming into an elite winger.

“They wanted Robitaille and I said, ‘No way, you can’t get Robitaille’ because I was still worried about some of the big arguments [to come over negotiations,]” McNall said.

The Oilers moved on to Carson. About two weeks prior to the trade, Carson received a phone call.

“Bruce McNall called me and said, ‘Hey, I just wanted to let you know we got a chance of getting Wayne Gretzky,’” Carson said. “I said, ‘What? Wayne Gretzky? It’s impossible!’ He said, ‘No, we do and the bad thing is they’re insisting on you and I’m doing my best to keep you out of the deal” is what he told me. So, I said, ‘Okay, do your best’ and I just kind of forgot about it.”

Though originally loathe including the Southfield, Mich., native, McNall came around to idea of building his package around Carson.

“With Jimmy Carson, it was a matter of…well, Jimmy is a first-line centre and now he’s going to be a second-line centre with Gretzky,” McNall said. “Maybe it would make some sense to be able to suffer losing Jimmy and that’s where that decision came about and that’s where that was settled.”

The last obstacle to overcome for McNall was Gretzky himself. In July of 1988, Gretzky married actress Janet Jones at Edmonton’s St. Joseph’s Basilica. It was the closest thing to a Canadian royal wedding, as it was broadcast live across the country. With his personal life undergoing big changes, McNall didn’t want to upset his professional life, as well.

“I asked Peter,” McNall recalled. “I said, ‘Peter, I don’t want to make the deal and find that Wayne’s unhappy…that’s the last thing I want.’ So I said I need to talk to him and he wouldn’t allow it.”

Pocklington’s refusal wasn’t going to stop McNall.

“As often in my life, as you know, I tend to ignore rules, I guess - no news there, right?” McNall said. “So I called Wayne. He was in L.A. at the time and we knew each other somewhat.”

Though skeptical at first, Gretzky came around to the idea in large part due to a phone call from Pocklington – one that Gretzky wasn’t supposed to be a part of.

“Wayne was in my office and we were discussing the possibility of this really happening and Peter called and I put him on speaker,” McNall said. “I wasn’t even thinking. I just hit the button to put him on the speaker and Peter started talking about the trade and saying a couple of things about Wayne, saying he’s going to whine about this and whine about that, that kind of thing. And then when we got off the phone, Wayne said, ‘Okay, I’m a King now’ and so I said okay.”

With Gretzky fully on board, McNall went about finalizing the deal.

“What actually happened was Wayne and I became conspirators in the deal,” McNall said. “Wayne started helping me figure out who to get. He said, ‘I am going to need Marty; he’s tough and he’ll protect my back. Krushelnyski is a good guy to have.’ At that time, we had to give draft picks and Wayne said do not give them consecutive draft picks all in a row. Let’s separate them and give them one first rounder every other year. I said okay and we got that done.”

Though he had forgotten about the trade weeks earlier, Carson’s memory was jarred in a hurry.

“A few days before the trade, I started reading a few reports and hearing about it,” Carson recalled. “I thought, my goodness, if this happens that could be amazing for hockey, amazing for the Kings…but I hope I’m not…you know, I’m 19 years old and we have already started negotiations to redo my contract.”

It was all for naught. The deal was done.

“I got the call and within a half hour my phone - you know, back then there were no cell phones - was ringing off the hook,” Carson said. “People [were] knocking at my front door. There were media people, ESPN calling, CNN and I was just like, what the heck is going on?”

While the trade was ostensibly about Gretzky, Carson was swallowed up in the hype all the same.

“Wayne Gretzky just got traded and I’m in the trade,” Carson remembered. “And then the media was all over me. When I say all over me, I don’t mean in a bad way; I mean like in a wanting access to me and so it was just very tough. It was an interesting… with so many emotions. I just got a house, I just got it outfitted, now I’m traded and I am waiting to hear from the Oilers. And then it’s a matter of them wanting me to there for a press conference and it’s like, where am I going to move to? It’s just stuff you’re just not used to as a 19-year-old.”

Even McNall and the Kings weren’t ready for the maelstrom it precipitated.

“I knew it was going to be big, but in no way did I think it was going to be of the magnitude it became later on or we recognized it to be,” McNall said. “Even Wayne, I don’t think, even thought…I mean, he thought it was big, too - we both did - but I didn’t think either one of us thought it was going to have the long-range effect that it actually had.”

For his part, Krushelnyski felt fortunate to be part of Gretzky’s plan.

“I was very pleased at the time,” Krushelnyski said, “but I think Gretz was just looking to make sure we had a balanced portfolio, so to speak, and I was lucky enough to be involved.”

Dividends began to pay off immediately for the Kings. Attendance skyrocketed from an average of 11,667 a night in 1987-1988 to 14,875 in 1988-1989. It was a circus everywhere the Kings went.

“When we went to the training camp in Victoria that year, it was an absolute zoo and our phones were ringing off the hook for season’s tickets,” McNall said. “We had to hire new people, completely re-staff the place and the whole thing was just impossible to handle. I began to realize this was going to be pretty big, really big…I think it probably really didn’t completely come into play until I could see the effect we had on the road….going to different cities that didn’t have hockey and selling out from every arena around from [exhibition games in] Tampa Bay to Phoenix to Las Vegas…that’s when it led to the idea that maybe hockey could be big and popular in areas like what we have today like Dallas, the [Anaheim] Ducks and all the rest of it and Nashville [played] in the Stanley Cup Finals! Never thought of that.”

In Alberta, there was a different kind of upheaval.

“I think there was shock more than anything,” Fuhr said of the aftermath. “I think everyone was really surprised that it happened and through training camp we all realized that we had to bear down and prove that we weren’t just one dimensional, that we could still win. I think it made everybody kind of look at themselves and push each other to play a little bit better.”

For Carson, acclimatizing himself to his new surroundings would prove to be a challenge. How do you go about replacing Wayne Gretzky?

“I was not nervous in my hockey ability,” Carson said. “I was nervous that these are the Stanley Cup champions. They were the team of the ‘80s, dynasty-type stuff and I knew that Wayne was obviously the greatest player in the world and this was just a huge thing. Then I realized the enormity like they were trying to have Parliament, the Canadian Parliament to have official proclamation, trying to rescind the trade, international interest; it was so much bigger. I was just like in a fog in the sense that I would just have to go and do what I could do.”

Despite moving the franchise cornerstone and a key member of a tight locker room that grew up as pros together, Fuhr says the Oilers players didn’t hold any animosity over the trade.

“I think for a lot of the guys, you realize it’s a business and that first and foremost that proved it was a business,” Fuhr said. “It wasn’t so much about being raised as family, that sort of thing - it became a business.”

But for fans at the Northlands Coliseum, seeing an Oilers team without a No. 99 on the ice for the first time in a decade was a hard proposition to swallow.

“I don’t think there was resentment,” Carson said of the fans. “I think there was resentment at the trade. I think the problem is I was always a symbol of the trade so it was not a question of overtly anything against me but it’s when you’re that symbol, you’re that symbol.”

Fuhr agrees.

“I think [Carson] got a fairly rough ride from the fans,” Fuhr said. “There were big expectations for him; the fans obviously watched Wayne all along so there were some high expectations.”

While Carson was struggling with change, there was no such problem for Krushelnyski.

“You say, ‘See ya, boys!’ and you walk in and make 25 new friends,” he said of his move from Ednmonton to L.A. “There’s always a couple of guys you don’t blend well with, but that’s on every team and [everywhere], really.”

On the ice that season, the Oilers took the step back that was expected, finishing third in the division. The Oilers’ 84 points were the fewest the team registered since the 1980-81 season, their second campaign in the NHL.

Carson, though, starred in his new surroundings, notching 49 goals and 51 assists. Still, he knew that wasn’t going to be good enough.

“I know [I scored 49 goals], but Wayne Gretzky scored 92 goals in a year,” Carson said. “At the end of the day, it was like, ‘How could they have traded Wayne Gretzky?’ is what I think a lot of people were thinking and they couldn’t stand Peter Pocklington and they were hanging him in effigy.”

Gretzky and the Kings thrived in L.A. The Great One scored 54 goals and added 114 assists en route to his ninth Hart Trophy. The Kings’ 91 points was the club’s best total in eight seasons and the team finished second behind the Flames for their best finish in the Smythe since realignment in 1981.

Naturally, the Oilers and Kings were fated to meet in the first round of the Campbell Conference playoffs.

Both teams were desperate to make a statement.

“Oh, my God, it was about as bad as you could get,” McNall said. “I think everybody there would have done just about anything, gone through any kind of hoop you can imagine to win that series. It was such an emotional big deal. It was unimaginable.”

The feeling was mutual in the Edmonton locker room.

“Any time you’re playing against the best player in the game, you obviously want to beat him,” Fuhr said. “We were all proud so we wanted to win.”

After splitting the first two games, the Oilers – in defence of their Stanley Cup – opened up a commanding 3-1 lead in the series with Carson scoring in Games 3 and 4.

But the Kings would fight back, taking Games 5 and 6 to force a deciding Game 7 at the Forum.

It was there that Gretzky showed the local faithful why McNall tried to move mountains to acquire him. The Kings won the game 6-3 with Gretzky opening the scoring less than a minute into the game and then icing it with an empty-netter.

The series might not have been a referendum on the trade, but it certainly felt like one.

“I think in a way it was,” McNall said. “It definitely showed what he meant and what the whole thing meant to the culture of L.A. and then Edmonton, of course, a year after that, went on to win the Cup again. It was just pretty crazy.”

The Kings would go on to be swept out of the playoffs in the Smythe Division final by the eventual Stanley Cup champion Flames.

Though the Oilers would go on to win the Stanley Cup in 1990, Carson wouldn’t be part of that team. Only four games into the 1989-1990 season, Carson was moved in a six-player trade to the Detroit Red Wings that saw Adam Graves, Petr Klima and Joe Murphy head to Alberta.

The Oilers’ centerpiece of the Gretzky trade was gone after little over a single season.

“I think there were a variety of reasons [why it didn’t work out in Edmonton], but I think at the end of the day, it was just a huge culture shock for me and I think for the team; the whole Gretzky trade and everything,” Carson said. “I actually had a pretty good year: 49 goals and 100 points. But looking back, some of the greatest players I ever played with were on that team.”

Was there a certain sense of relief in leaving Edmonton for Carson?

“I don’t know,” Carson said. “I think it was a new challenge. As you get older you think about things differently…maybe a little bit of getting out, but I think the Edmonton fans were great fans, very informative hockey fans and some of the players I played with were some of the best from their era. I think back to Jari Kurri, Kevin Lowe, Mark Messier, Craig Simpson, Grant Fuhr, Glenn Anderson, Charlie Huddy, you just go on and on and on…Billy Ranford. It was just amazing players, so I think at the end, it just didn’t work out and I actually look back and I remember that year was a lot of fun. I wish we would have done better….we were up 3-1 against the Kings and lost it.”

In California, McNall got what he wanted from the Gretzky trade, but never a Stanley Cup. But McNall believes that’s okay.

“I think we all would look at that and say that was the only real missing piece of it all,” McNall said. “And if you look at the bigger picture, I guess one could say, you know the Cup was - I hate to put it this way - but it was almost secondary to getting the sport popular in places that it wasn’t before; L.A. obviously being my focus, but other places as well. Because now kids and everybody love to go to games and that’s part of their society in the world for them, for those folks and maybe in some way, that’s even more important than the Cup.”

The closest he would come was in 1993 when the team reached the Cup Final. In loading up for that year’s playoff run, the Kings brought back Carson before the trade deadline, allowing the two men who would forever be associated with The Trade to play alongside one another.

“It was so exciting for the city of L.A.,” Carson recalled. “The team had had minimal success over the years and here we are in the Stanley Cup Final, so that was an amazing run—we came up a little short, but it was great for the city.”

That run would effectively be the end of McNall’s tenure with the Kings. In December of 1993, he defaulted on a $90 million loan from the Bank of America and was forced to sell the team by the following spring. In 1997, McNall was sentenced to five years in prison for bank fraud. He was released in 2001.

Three decades after the fact, Carson remains inextricably linked to The Trade, something he’s at peace with.

“I often think if the trade had never happened, what would have occurred - you don’t know,” Carson said. “So there are a lot of players like that who could have, maybe, never made it or made it and done a lot better. I don’t really spend a lot of time on that. I am actually very thankful that I had an opportunity to live a dream of playing in the NHL.”

Carson has now found a successful career in finance not far from Detroit after leaving hockey at the age of 30. Now Carson sees himself as more of a finance guy who used to play hockey than an NHLer working in finance.

“It’s funny because with a lot of people I often meet, I never bring hockey up and I don’t do that because I’m embarrassed,” Carson, now 50, said. “Number one, I don’t want to be a showboat. I am very proud of the opportunity I had to play professional sports especially in the NHL. However, I don’t want that to define me as a person going forward. I always will look back fondly and if people want to talk about it, I talk about it.”

For McNall, having The Trade as the biggest mark he made in sports is gratifying.

“It’s something I did not do for that reason at the time, but yes, I am happy at the fact that I have that footprint,” McNall said. “I’m proud of it and it makes me happy and every time I go to Kings games now and fans come up to me, I always get stories about how their kids would come to games and they found the sport at that time because of the Gretzky trade. And you know, families have come together; all kinds of wonderful stories and so it is a nice feeling.”

Thirty years later, you can still ask hockey fans of a certain vintage about The Trade.

You don’t have to specify. People will know the one you’re talking about. And they’ll remember exactly what they were doing on a lazy summer afternoon in 1988.

An earlier version of this piece ran as part of TSN.ca's Canada 150 coverage.