Aug 27, 2021

When the Milwaukee Bucks went on strike, and what’s changed since

The Bucks’ strike, which put NBA players directly in conflict with NBA owners, was a glimpse towards what athletes could accomplish on a larger scale.

This time a year ago, the Milwaukee Bucks took a step towards the radical. In protest to the police shooting of Jacob Blake last year — and amid the context of intensifying Black Lives Matter marches throughout the summer — Bucks players decided to strike during their Aug. 26 first-round playoff game against the Orlando Magic, calling for justice in the case of Blake’s shooting as well as broader, systemic change. Their decision led players across the NBA to join the strike as well, and then athletes from other leagues too. For the next few days, sports were sidelined to center a discourse about protecting Black lives.

It was a historic work stoppage. NBA players were reclaiming their power as the labour force of a business worth tens of billions and controlled by owners who are predominantly white and billionaires themselves. Athletes have expressed various forms of protests in previous years as individuals or in groups, but never anything on this scale. It was in the players’ hands to stop the business of the NBA, and that held the promise of profound change. You could get your hopes up. When it comes to massive social movements, the organized withholding of labour has always been a key catalyst for action. In his 1969 book The Revolt of the Black Athlete, Dr. Harry Edwards describes the movement among many Black athletes to skip the 1968 Olympics in protest to segregation and draws a line forward to a present-day “fourth wave” of Black athlete activism, in which today’s athletes can continue to leverage their power through protests for the welfare of Black communities everywhere.

A year later, the Bucks’ protest feels like a footnote in our collective memory. Two NBA championships have been won since. We’ve gone through multiple new waves of the coronavirus. Time has put a buffer between us and the Black Lives Matter marches that were so widespread in the streets last year, although that isn’t to say that activists aren’t still waging and in many cases winning fights to create positive change within their own communities. While it held transformative promise, we should reflect on the past year and whether or not the Bucks’ decision to strike truly led to transformative outcomes.

Among the more obvious impacts from the strike are the concessions made by NBA owners in order to encourage players to return to work. Some of these were already in place after many players expressed hesitancy to return for the NBA restart in Orlando while the Black Lives Matter movement was so strong outside of the bubble, such as the introduction of general social justice messaging (“Justice,” “Vote”) on player jerseys. That the strike led more players to consider going home only added a sense of urgency to the matter.

Upon returning to play, the NBA and the players’ union announced new social justice initiatives determined together. These included the formation of a NBA social justice coalition, voter registration drives and messaging in favour of police and criminal justice reform throughout games and advertising. To be sure, these are concrete actions that followed from players choosing to withhold their labour, although they are considerably less radical in aim than the initial decision to strike.

One of the primary causes adopted by the NBA’s social justice coalition is the passing of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, a police reform bill that was drafted in response to the protests that followed Floyd’s murder. Among many other provisions, the bill includes a ban on the use of chokeholds or other carotid holds, the required use of body cameras and dashboard cameras on vehicles, and greater accountability and oversight measures. However, many activists decried the bill, arguing that it relied on reform and reinvestment measures that have historically failed to address police brutality or the systemic racism of the institution. “Justice in Policing, by its very name, centers investments in policing rather than what should be front and center — upfront investments in communities and people,” wrote the Movement for Black Lives in a letter opposing the bill.

Activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore has spoken of “reformist reforms,” or modest reforms to the criminal justice system that often placate more meaningful attempts to challenge or dismantle the root oppressive structures of said system, as opposed to non-reformist reforms that can be steps towards broader transformative justice. Reformist reforms are most concerning within the context of a mainstream institution — such as the NBA — attempting to meet the struggles of an ongoing social movement halfway. Often, a radical movement can be co-opted.

Compare the results from the NBA’s social justice initiatives to popular demands from Black Lives Matter marches at the time, and there seems to be a disconnect from the NBA’s messaging to what many young activists were calling for. How could television spots that made soft calls for reform compare to demands for defunding and even abolishing the police in the streets? Of course, corporate interests could never align with the struggle and interests of a grassroots social movement. While league messaging encouraged fans to vote, a report from The Ringer’s John Gonzalez found that 80.9 percent of NBA owners’ political contributions — barring one donation deemed an outlier — went towards Republican candidates and causes. Many of those are in opposition to what players are fighting for; Republicans in the House of Congress voted against the Justice in Policing Act and delayed the bill’s passing in 2020.

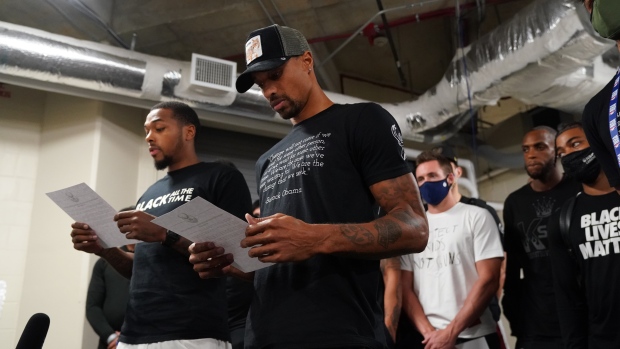

Individually, there were many NBA players that expressed honest, raw emotion and in some cases real scars in response to racial injustice last year. Players made an optimistic decision to recount their trauma publicly, sharing stories of what it was like to grow up and live as Black men in America. Then-Bucks player Sterling Brown, who was key to his team’s decision to strike, was tased by a Milwaukee police officer in 2018 and has spoken often of his experience with police brutality. When the Bucks announced their decision to strike, Brown, along with teammate George Hill, read the statement on behalf of his teammates: “Despite the overwhelming plea for change, there has been no action, so our focus today cannot be on basketball.”

There were other players that attended protests in person and put their own money into meaningful programs and initiatives. Some even placed themselves in community with the activists who have been involved in Black Lives Matter and similar movements for many years running, and this was especially visible with the WNBA player base who has been for years at the forefront of progressive athlete-activism. Natasha Cloud and Renee Montgomery joined Maya Moore by opting out of the 2020 season in order to dedicate themselves to community activism; Montgomery has since replaced her team’s previous owner, Republican Senator Kelly Loeffler, after Atlanta Dream players protested her opposition to the Black Lives Matter movement. Layshia Clarendon became one of few athletes anywhere to advocate for the defunding or abolition of police, a movement that gained significant momentum in the mainstream last year.

Individuals, however, can’t solve a problem that runs systemic. For all of the resources that LeBron James, for example, has available to him, he alone can’t take the place of a collective effort to challenge existing power structures. The Bucks’ strike, which put NBA players directly in conflict with NBA owners, was a glimpse towards what athletes could accomplish on a larger scale.

Before players agreed to return for the bubble restart last year, Kyrie Irving led a mass Zoom meeting urging his peers against resuming the season. Irving, like some players around the league, worried about the NBA drawing away from the momentum of Black Lives Matter in the news cycle or being unable to attend protests in person while in the bubble. “I’m willing to give up everything I have,” he said. Others argued that they could do more for social change by collecting their salaries, re-investing in their own communities and advocating for change while playing. In the end, the players voted to finish the season, including Irving after he was unable to convince a majority to his side. The night that the Bucks chose to strike, however, still goes down as the night that held the most promise for meaningful change.

As the business of basketball continues to chug along a year later, perhaps that’s what we’ll remember most from the day the NBA stopped — the signs of collective power.