Sep 14, 2020

The long change a short answer for creating more offence

The easiest way for the NHL to organically increase offence is to expand on the existing ‘long change’ rule, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

If you have been watching the 2019-20 Stanley Cup Playoffs, you have surely seen some nerve-wracking second-period moments.

The second period has become the sweet spot for the National Hockey League, a period where you tend to see more counterattacking opportunities and scoring chances from dangerous areas of the ice. The added chaos is by design. And though many things have changed in the era of bubble hockey, the bedlam experienced in the middle frame hasn’t changed in the slightest.

The second period is synonymous with the long change. At the end of the first period, goaltenders will switch sides of the rink, which means skaters on both teams have to skater further away from the bench to defend the net.

The inherent risk of having to cover so much more distance does have an impact on how coaches and players treat the second period.

As one example, players who are bottled up in the defensive zone for an extended shift have to work that much harder to get a change. In some cases, that change either takes substantially longer than it should have (like Islanders defenceman Nick Leddy’s three-minute shift against Philadelphia), or simply never comes.

We know two things to be true about the second period: players are forced to take longer shifts and teams tend to score more goals. The latter piece is nuanced and complicated – we rarely, as one example, see score effects plague the second period quite like they do in the third period, so it is not a complete apples-to-apples comparison. But we do know that longer shifts correlate with deteriorating performance and added defensive miscues.

If we look at the 2019-20 post-season data, we can see how dramatic this shift is.

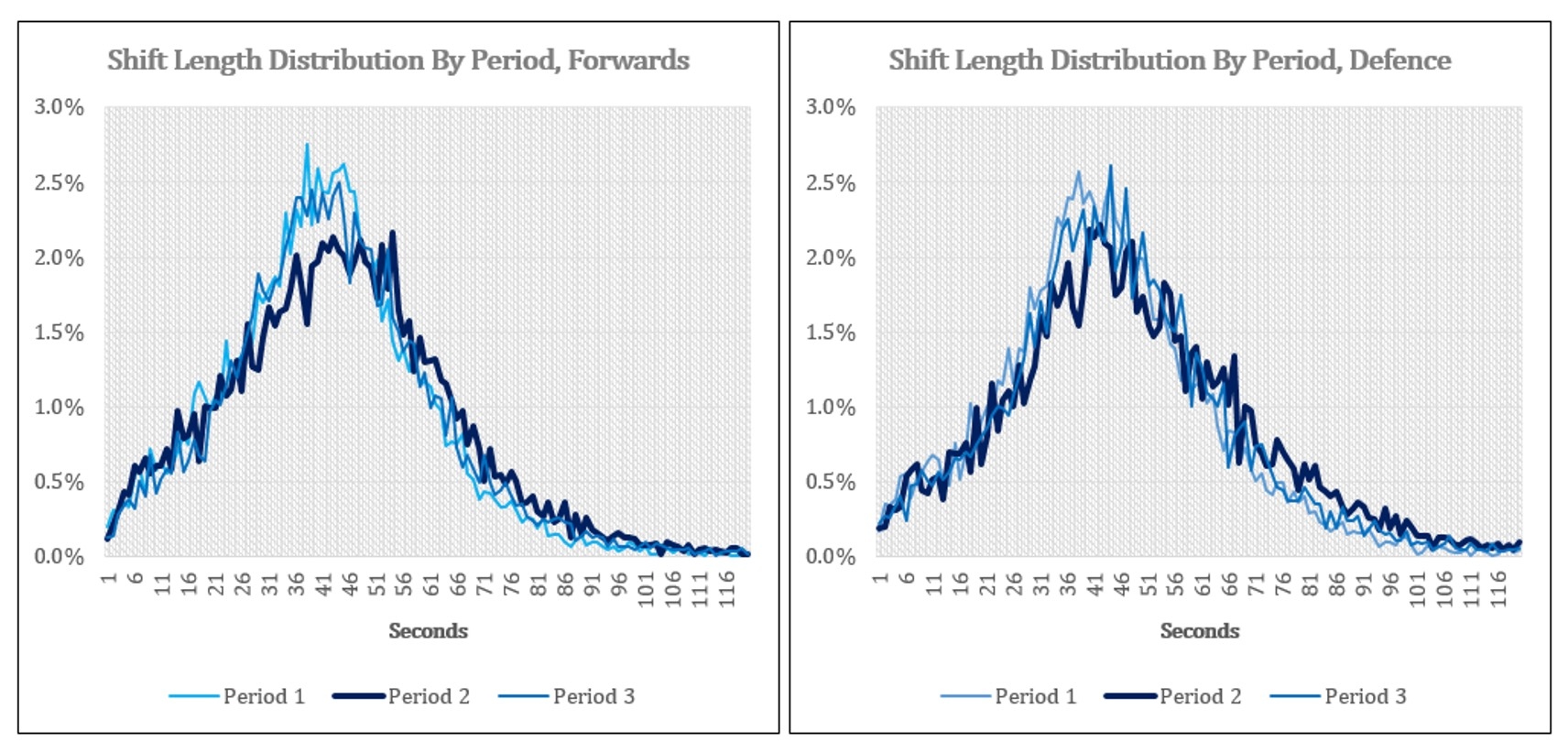

In the first period, we see a fairly predictable rate of 40-second shifts for forwards with less relative deviation; second-period shifts for forwards are, on average, five seconds longer with much higher deviation. Defenders see a similar trend: 44-second shifts with less deviation in the first period, growing to 50 seconds (again, with more deviation) in the second period:

Not only are shift lengths much less predictable, there is also a definitive rightward skew. By way of example: forwards and defenders are twice as likely to be forced into a disastrous shift – I’ll use 90 seconds or more to define it here – in the second period than they are in the first.

Why should we care? It comes back to the element of scoring, or even more generally, offence.

A common refrain around the league, particularly in the playoffs, is that the absence of scoring generally correlates with less entertaining games. There have been dozens upon dozens of debates as to how to create that offence organically; I submit that the easiest way to do this is to merely expand on the existing “long change” rule the second period carries, an idea proposed a few years back.

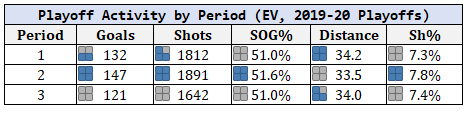

Just look at 5-on-5 play this postseason:

You can sample most years and find similar trends – scoring and shooting volumes are higher, shooting percentages are higher, the percentage of shots that end up on goal is higher, and average shooting distance decreases.

There are likely a number of reasons why this is the case, but there is no doubt that the added difficulty in starting and ending shifts due to sheer skating distance has been a major driver.

At some point, you wonder if the hockey executives who meet to discuss proposed rule changes for upcoming seasons will revisit this topic. We know the league wants marginally more offence – it’s why the reduction of goaltender equipment size was recently ratified by the NHL and NHLPA.

Perhaps this postseason has given us another subtle option to make life a little more difficult on defences around the league. Doubling the long change (i.e. first and third period, in lieu of the second period only) or making the long change standard operating procedure could do just that.

Coaches may not love the idea. As for everyone else, it’s worth another discussion.