Jun 9, 2016

How the Penguins are helping Matt Murray shine

Pittsburgh Penguins rookie goaltender Matt Murray is having a fantastic postseason behind a team that has improved at limiting high-quality scoring chances, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

If there has been one breakout performer of this year’s Stanley Cup playoffs, its Pittsburgh Penguins goaltender Matt Murray.

Murray, who assumed the starter role in Pittsburgh after Marc-Andre Fleury’s second concussion of the season, has been downright fantastic for a Penguins team that’s been beleaguered in the past by shaky postseason goaltending. His 92.5 per cent stop rate through 19 games is third best this postseason among goalies who have logged at least 10 games, trailing only a pair of Vezina Trophy candidates in Braden Holtby and Ben Bishop.

It’s a fantastic organizational development, but Murray’s development into a potential long-term answer for the Penguins in the crease does involve some curious timing. After all, it was just a few months ago that some – including this space – noted that Fleury was seemingly turning a corner. It had looked like years and years of investment into turning the former first-overall pick into a reliable No. 1 goaltender was finally starting to pay off.

Murray’s emergence means Pittsburgh is going to have to make a decision in the near future. From a pure cap perspective, it would seem that – assuming the team has full confidence in Murray going forward – parting ways with Fleury and his $5.7 million cap hit through 2018-19 makes the most financial sense. Combine that with the fact that Fleury had a strong season, and you have a potential opportunity to part ways with a player that could net you a very real return.

But, I do think it’s worth noting that something a bit curious has happened in Pittsburgh this year – something that might have helped Murray and Fleury turn in their strong performances.

One of the first things I look at when trying to capture or forecast performance — after save percentage — concerns the type of shot quality a goaltender has faced. For most netminders this is just a sanity check of sorts. Your middle 25 goaltenders are generally facing relatively comparable types of shot quality difficulty, so trying to find differentiation on this front becomes something of a non-value-added task.

However, the Penguins took a demonstrable step forward defensively this year on limiting some of the types of shots statistically proven to find the back of the net with more regularity than others. This would include both rebounds (somewhat in a goaltender’s control) and counterattacking shots.

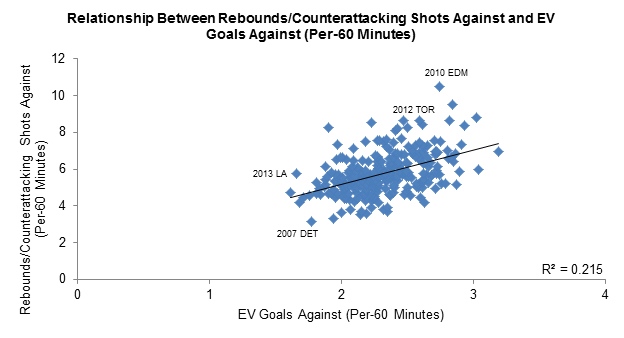

Historically, teams that limit both rebound attempts against and counterattacking shots against do a decent job at suppressing their goals-against rates. This has been borne out over nearly a decade of regular season data.

Generally speaking, you can see that as teams bleed more rebounds and counterattacking shots against they give up more goals. This may seem intuitively obvious, but it’s always nice to see that this type of relationship can be quantitatively observed. (It’s worth pointing out that we see similar relationships between things like shots against/60 and goals against/60 because volume remains the most significant driver of goal rates.)

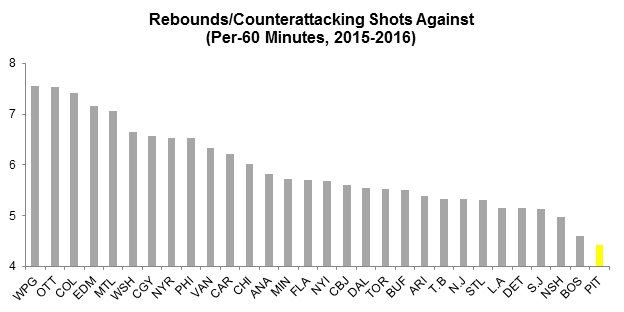

This brings us back to the Penguins of 2015-16. I mentioned that this club had really tightened things up on mitigating these difficult shots. In fact, they were the league’s best unit at doing so.

As you can see, most of these teams are generally indiscernible from one another. Playing goalie in Florida pretty much means the same thing as playing goalie in Anaheim, Minnesota or any of another 20 or so cities this season.

But at the poles there are real disparities. A goalie in Winnipeg, for example, would’ve faced about four more rebounds or counterattacking shots against than a goalie in Pittsburgh every 60 minutes. When you consider that teams play around 4,000 minutes at even strength a season, you realize that this type of incremental shot volume starts to add up. And this doesn’t even get to the fact that a team like Winnipeg bled shots from other areas of the ice at the same time. It’s hard for a goalie at any talent level to keep goal numbers down in such an environment.

This postseason has been more of the same from Pittsburgh. Teams have been mostly unable to generate higher-quality chances against them. When they have managed to, Murray has turned them aside.

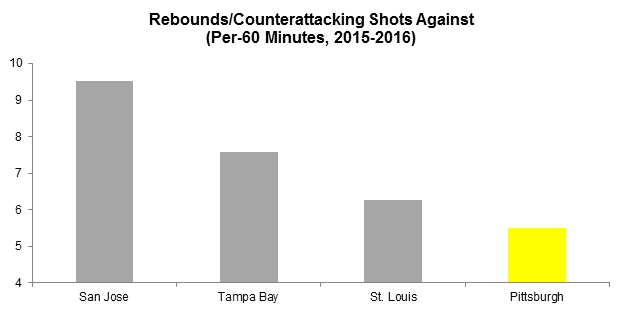

For the four conference finalists this year, you can see that Pittsburgh has been the best at easing some of the burden on their goaltender. Note the stark contrast from the San Jose Sharks:

Interesting piece of data, isn’t it? No one’s ever really mistaken Pittsburgh for some elite defensive team, and by our single-best statistical metric on the defensive side (shots against per-60 minutes), the Penguins were probably somewhere between average to above average this past regular season.

But, it does seem as though the Penguins have found a way to alleviate some of the defensive zone stresses by taking away some of the most deadly forms of attack in hockey. To that end, perhaps it’s not all that curious that both Murray and Fleury took a step forward this year. What’ll be interesting to see is if this trend sustains for multiple seasons, and if the Penguins will evolve into one of the league’s better two-way hockey teams.