Apr 13, 2020

NHL rosters continue to trend younger

Just one in 10 regular skaters during the 2019-20 season was over the age of 32 – the lowest percentage in league history, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

One in 10.

If you needed more evidence that pro hockey was increasingly becoming a young man’s game, consider this fact – just one in 10 regular skaters during the 2019-20 season was over the age of 32, the lowest percentage in league history.

Much has changed in the NHL over the years, but one of the evolutionary staples of the league has concerned player age.

There have been two drivers of the change. First, irrespective of which aging curve model you are looking at (here is one), the consensus is that both forwards and defencemen have their peak performance years in their mid-20s. Second, the league’s hard salary cap system incentivizes teams to find productive cheap labour, and there is no better player pool than freshly drafted teenagers on entry-level contracts.

With performance and contractual incentives aligned, teams began focusing on leveraging younger talent throughout their lineup – a shift that really started after the 2004-05 lockout and has only strengthened with time.

Similarly, teams began replacing the older players in their lineup – perhaps due to performance degradation, perhaps because of the size of their contracts, or perhaps a combination of the two – with their younger, cheaper counterparts.

There is one wrinkle to this, of course: teams don’t want to bring players into the league merely because they are young and cheap. Burning a year off of a player’s entry-level contract is a big deal. If nothing else, it brings that player (whose true value may not yet be known) a year closer to his second contract and an expected pay bump.

What you are left with are two objectives: teams trying to carve older players out of their organization, and teams being strategic with injecting young talent into the lineup.

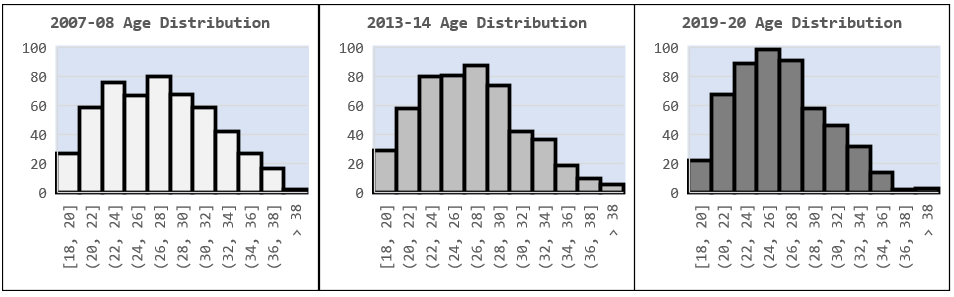

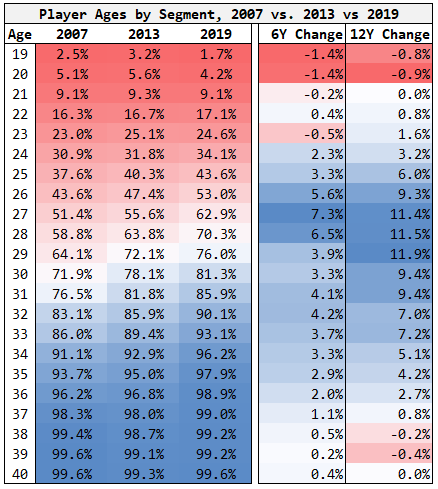

If you look at how player ages have evolved over the years – I’ll start in 2007-08 and work on a six-year interval – you can see that the NHL has found a true sweet spot, where more than half of the league currently sits between the ages of 22 and 27.

It is an interesting dynamic for any number of reasons, but one thing that remains a point of interest for me is how the NHL’s player union views this trend.

Unions are designed to protect their constituents. But in a zero-sum game like the NHL, where the salary cap is fixed and the number of roster slots finite, a favourable change for one age group means an unfavourable change for another. The union has certainly done well to enrich players signing on for their second and third contracts, but it has come at the cost of older players pushed out of the league earlier than their predecessors were.

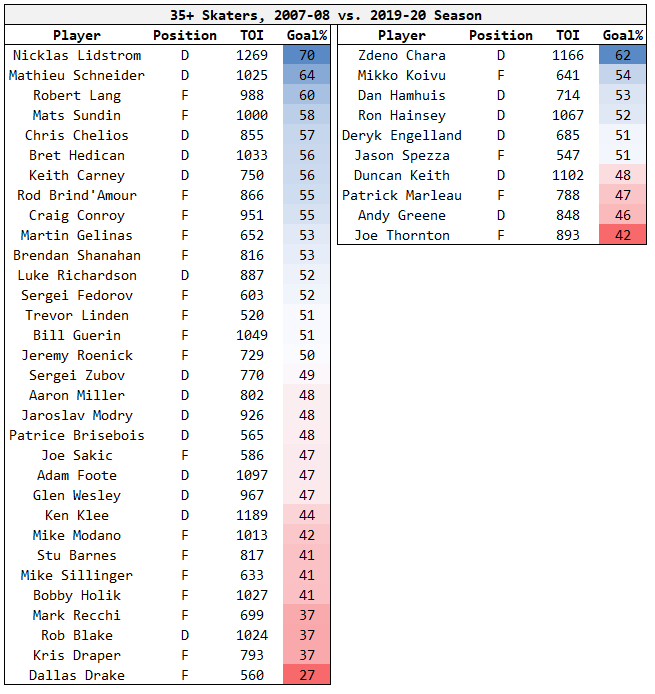

Perhaps the best way to illustrate this is at a micro level. If we look at the 35+ age group from the 2007-08 season versus today, we not only see a massive disparity in the number of skaters that satisfy our criteria, but we also see a gap in performance.

Most of the 35+ skaters in the 2007-08 calendar season may not have been in their peak performance years, but there were still a number of productive contributors. The 2019-20 season? It was almost impossible to find a 35+ skater, and if you did, it was likely a defenceman. (Teams continue to remain more aggressive in both promoting young forwards and displacing older forwards relative to their defencemen counterparts.)

In many ways, the NHL has followed alignment of the other major sports leagues through the power of data – an ability to isolate on how age can impact performance and availability, and aligning their financial and operational strategy accordingly. But it didn’t take 30 years to get here. The league is continuously learning and studying in real-time, and a lot has changed in 12 seasons.

So much so that it felt like the 2007-08 Stanley Cup champion Detroit Red Wings – with an average age of 29.5! – were playing a different sport.

Data via NHL.com, NaturalStatTrick, Hockey Reference