Oct 29, 2019

Kopitar, Doughty contracts loom large for rebuilding Kings

Drew Doughty and Anze Kopitar were two of the best play-driving skaters in the league but the advantages they’ve carried over teams for years have eroded to the point where the Kings’ ‘top unit’ is struggling to drive results and they’re still being paid like superstars, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

I’ve been thinking about that famous quote from philosopher and essayist George Santayana while watching a few of the rebuilding franchises around the National Hockey League.

We talked about the rise and fall of two of the greatest franchises of the last decade – the Detroit Red Wings and Chicago Blackhawks – last year. By design, the NHL induces long-term parity, and it’s unlikely either of these teams would have been able to avoid slippage in the standings. But handing out a series of legacy contracts and failing to capitalize on draft picks ended up being a death knell for both, and now the fan bases have to sit patiently as the team’s cap situation sorts itself out. (It’s also worth mentioning there are examples of better cap management sustaining organizational performance over longer periods – ask the Boston Bruins and San Jose Sharks about that.)

That brings me to a third team in the Los Angeles Kings. The Kings picked up where the Red Wings and Blackhawks left off, dominating the earlier parts of this decade en route to a pair of Stanley Cups. Their style of play – a militaristic buy-in to a dump- and-chase style of hockey with hyper-aggressive forechecking – threw opponents for a loop, and most of their core talent was on the right side of the aging curve.

But the Kings, much like the Red Wings and Blackhawks before them, have struggled to adapt. A more modern offensive game, one that’s become increasingly apparent over the last five seasons, has neutralized Los Angeles’ defensive advantage and put a massive spotlight on an increasingly ineffective attack.

They also struggled with the transition off the ice. Those legacy contracts still haunting the Red Wings and Blackhawks are starting to come home to roost for the Kings. Across five players – Jonathan Quick, Anze Kopitar, Drew Doughty, Jeff Carter and Dustin Brown – the team holds about $200 million in long-term cap liability, and that’s excluding other contractual messes like Dion Phaneuf’s four-year buyout or Mike Richards’ recapture penalty.

Those contracts range from regrettable to utter disasters. But the most curious players in that group are Kopitar and Doughty. Absent Quick’s playoff goaltending performances, I doubt you could find players who were more responsible for the pair of Stanley Cups. But that was some time ago. Here we are, in 2019, where Kopitar ($10-million AAV through 2023-24) and Doughty ($11-million AAV through 2026-27) are still paid like superstars, but may not be producing like superstars.

At their best, Doughty and Kopitar were two of the best play-driving skaters in the league – Doughty from his swift north-south transition game, Kopitar from his two-way acumen and playmaking abilities in the offensive zone. But the advantages they’ve carried over teams for years have eroded to the point where the Kings’ “top unit” is struggling to drive results.

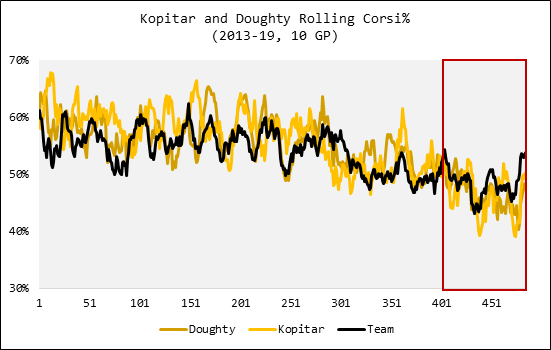

Consider the way both of these players have impacted Los Angeles’ shot share over the last six seasons:

You can almost see the three phases of the Kings transition here – from elite Western Conference team, to Western Conference playoff team trying to hang on, to a team that’s now getting outshot on a relatively routine basis. The most fascinating part of the graph is what has happened over the last 80 or so games where Los Angeles actually carries more of the play with their top unit off of the ice than on, and it’s been that way for some time.

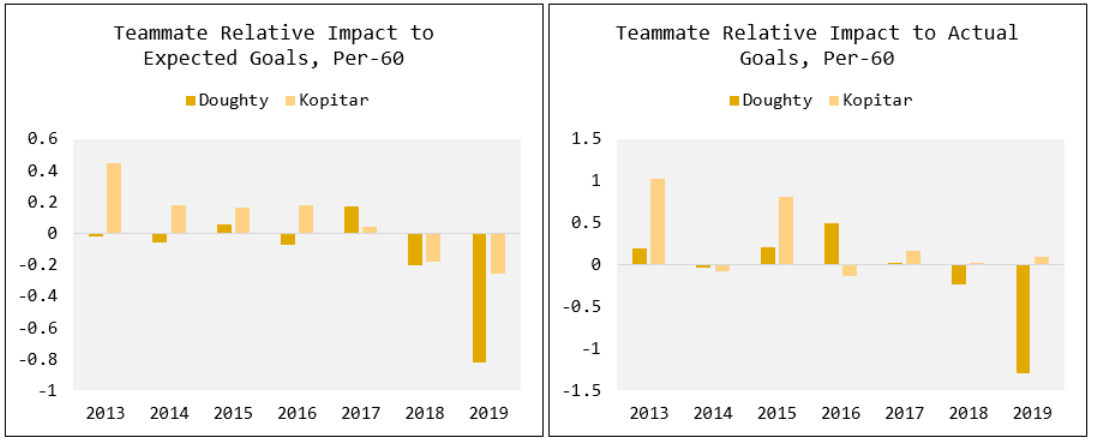

Those relative numbers may not be obvious from the shot share – especially with Los Angeles’ general puck dominance eroding over a similar timeline. But one thing we can do is look at how each player has individually impacted his teammates’ performances over the years. We tend to see true stars drive favourable shot shares, scoring chances, expected goals, and, over longer samples, actual on-ice goal differential. That’s what we saw from Kopitar and Doughty until recently:

It is hard to imagine that both players have lost their game. There is a new head coach in town and the roster still leaves a tremendous amount to be desired – it is, after all, a team in the middle of a rebuild.

But to call it concerning that Los Angeles’ superstars are having such a hard time positively influencing their teammates’ play and the play of the team more generally would be an understatement. If not because these are the early signs of real age-induced performance degradation, then because the team is married to both players for the distant future.

Data via Natural Stat Trick, Hockey Reference, and Evolving Hockey