Jan 22, 2018

NHL is headed for more skewed first-round playoff matchups

The league’s current postseason format compromises the spirit of the regular season, Travis Yost writes.

By Travis Yost

When the National Hockey League introduced its new playoff format for the 2013-14 season, the spirit of the format was to enhance the race for postseason spots and further intensify geographical rivalries.

It was in some ways a sensible bet. The league sees a ratings boon any time two local rivals meet in the postseason and it often makes for compelling hockey. Get the right matchups and the NHL’s business can prosper.

But that bet came with a price on the competitive fairness front. The league has long struggled with the right recipe for getting the best 16 teams into the playoffs. The newest format doesn’t help with that objective in the slightest. The trade-off with emphasizing divisions is that the league has often found itself with inferior teams in the postseason merely because of playoff formula inefficiencies.

What do I mean by playoff formula inefficiencies? There are two. The first is that teams are bucketed into conferences due to travel constraints. This works just fine if the conferences are reasonably split in talent, which generally is the case. But in the seasons where there is a notable skew in talent distribution – think a few years ago when most of the league’s top teams resided in the West – there’s a good chance that an inferior team from one conference will make the playoffs at the expense of a superior team from the other conference.

The second inefficiency is much more restrictive, and it was borne out of the 2013-14 format’s emphasis on divisions. The NHL essentially took the conference inefficiency and doubled-down. Instead of taking the eight best teams from a conference, they now mandate at least three teams from each division, plus two wild cards. Not only does this mean potentially undeserving teams getting into the postseason, it also opens up the door for bad first-round playoff matchups.

It happens every year. Just a few quick examples to emphasize this point:

In 2013-14, the 100-point Montreal Canadiens had to open on the road against 101-point Tampa Bay. Philadelphia (96 points) earned a home series against the 94-point and Metropolitan three seed New York Rangers. Meanwhile, the third seed in the Pacific Division (L.A. Kings) had to play 111-point San Jose in the first round.

In 2014-15, the league’s 10th best team in Vancouver played the league’s 16th best team in Calgary. Meanwhile, the league’s sixth best team in Nashville (104 points) played the league’s seventh best team in Chicago (102 points).

In 2015-16, 97-point Tampa Bay played 93-point Detroit. The league’s best team, Washington, had to play 96-point Philadelphia. Also of note: Boston (93 points) didn’t make the playoffs, but Minnesota (87 points) did.

And in 2016-17, the Atlantic Division three seed in Boston (95 points) earned the right to play Ottawa, a 98-point team. The three-seed in the Metropolitan, 108-point Columbus, earned a matchup with 111-point Pittsburgh.

Why do I bring this up in the middle of January? A cursory glance at the 2017-18 standings shows that the NHL is again at risk on two fronts – weaker teams making the postseason and divisional seeding creating curiously skewed first-round matchups.

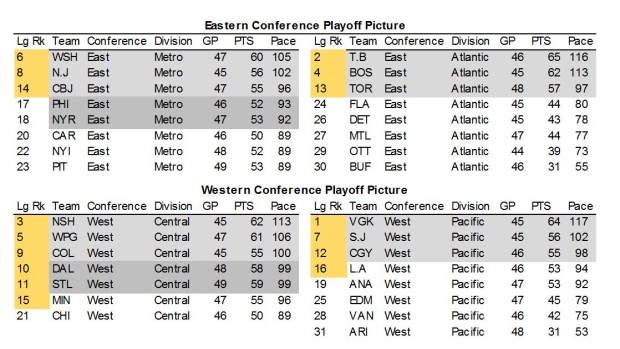

In the table below, gold indicates a “Top 16” points pace. Gray indicates projected playoff team based on the current playoff format. (Standings as of Monday)

There are a few things to digest here, but the most prominent is the fact that there is significant divisional imbalance again this year. The best example here would be 96-point Minnesota. The Wild are expected to finish sixth in the Central Division and outside of the playoffs. But they would finish third in the Metro (with a playoff spot), fourth in the Atlantic (with a playoff spot), and fourth in the Pacific (outside of a playoff spot). The mere existence of divisions can have them finish as high as a locked-in playoff team, to a wild-card team, to missing the postseason entirely.

Minnesota isn’t the only example. Ten of the league’s 16 best teams are in the West. Los Angeles, like Minnesota, is at risk of missing the postseason because of the strength of the conference. One of Philadelphia or the Rangers, both projected to finish below Los Angeles by point total, is likely to get in.

Let’s say you don’t particularly care about conference imbalance though – let’s say you chalk it up to unbalanced schedules and are okay with small variances. To that end, let’s focus on the divisional projections:

Columbus and Toronto are mirror-image teams – similar underlying numbers, similar point totals, etc. But Columbus is set to draw a New Jersey team in the first round that’s 11 points behind Boston. The same Bruins team that’s on pace for 113 points and only are at risk of not winning the division because of Tampa Bay’s existence.

The wild card is a gambit, too. Focus on Philadelphia and the Rangers for right now. One of these two teams is going to have to face the conference’s best team because of the crossover rule. The other will likely face the Washington Capitals – a quality hockey team, but only the sixth-best team in the league.

The West is just as much of a wreck. If the season ended today, Vegas – four points clear with the conference lead – would end up playing one of Dallas or St. Louis, both of whom are expected to finish higher than the Pacific third-place team in Calgary.

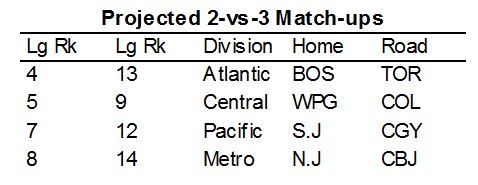

But again, the real issues are borne out of the mandated 2-vs-3 matchup in each division. The strength of the Central means that this particular matchup will be notably better than all others. I mean, consider the league rankings of each 2-vs-3 series:

Winnipeg’s likely reward for being one of the five best teams in the league is a punishing first-round series against a quality team. Meanwhile, weaker teams in San Jose or New Jersey will draw even weaker teams in Calgary and Columbus, respectively.

To some, the inefficiencies in the divisional playoff format are non-issues. Ultimately the best teams get into the playoffs, the worst teams miss the playoffs, and many teams at the top half of the league will still get in.

But to others, myself included, the new format has just caused more problems. Is emphasizing divisional rivalries worth compromising the spirit of the regular season – a regular season intended to get the best and most deserving hockey teams into the playoffs? I don’t think so. And while things like the scheduling imbalances are hard to fix, rolling back to the old conference-based playoff format would be an immediate improvement on the status quo. I hope the NHL hasn’t taken this debate off of the table.